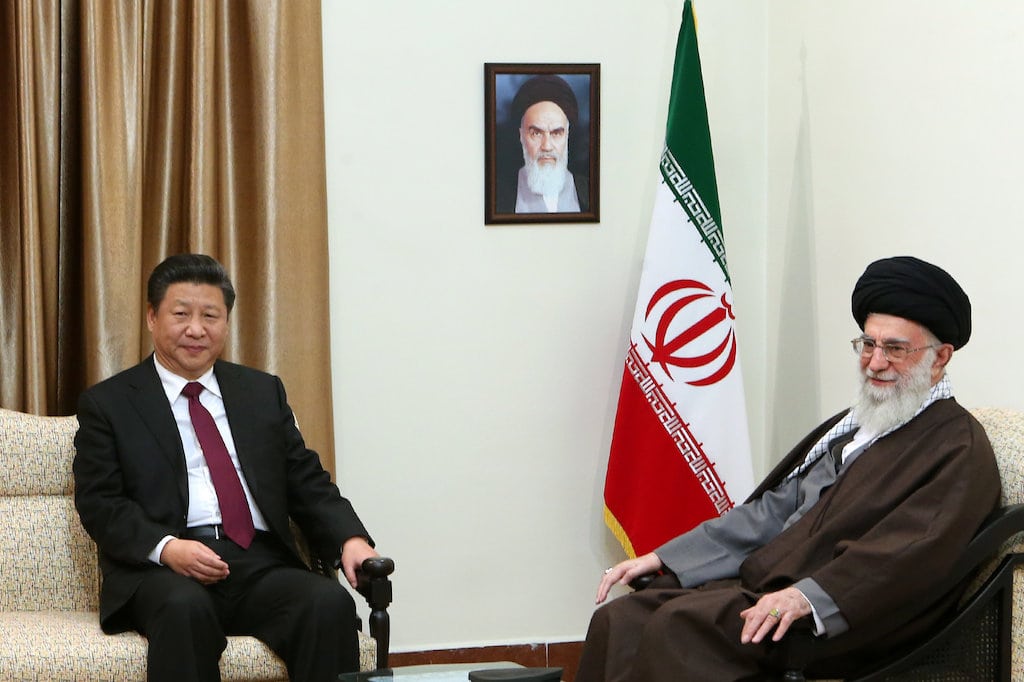

On March 27, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his Iranian counterpart Mohammad Javad Zarif signed a deal promising $400 billion in Chinese investment in Iran over the next quarter-century. Zarif called China a “friend of difficult days” and thanked Beijing for helping Tehran resist sanctions.

There will certainly be handwringing in Washington as partisans blame each other for bringing two adversaries together but, in reality, the two biggest losers will be both China and Iran. Frankly, it is a sign of the aloofness of both regimes that neither sees the train wreck coming.

Iranians are scarred by history. The British and Russian empires steadily encroached on Iran’s borders throughout the nineteenth century, wresting the South Caucasus, western Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and much of Baluchistan away from Iranian control. It was against this backdrop that Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896) reached out to the Austrians who formed the Dar al-Funun, Iran’s first modern military academy.

As dangerous for Iran as the erosion of its borders was the loss of its financial sovereignty. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the British and Russian empires targeted Iran (or Persia as it was called before 1935) with a series of exploitive loans to fund the shahs’ profligate lifestyles and inefficient administration. In 1872, for example, Baron Julius de Reuter signed an agreement to provide Nasir al-Din Shah a loan in exchange for control over many Persian industries and public works for a couple of decades and the majority of the revenue they would earn. While public outrage ultimately led to the cancellation of the Reuters Concession, Iranian schools still teach the episode as Exhibit A as to why Iranians should not trust grandiose business schemes originating with outside countries. In 1890, the shah repeated the error when he granted a British concern a monopoly over tobacco cultivation and processing, with the stroke of a pen dispossessing thousands of Iranians involved in the industry. The resulting protests—stoked by religious authorities in Najaf—paralyzed Iran and served as a prelude to the constitutional revolution just over a decade later.

Iranian leaders reached out to experts from countries they deemed disinterested in imperial agendas to restore financial independence or, at the very least, to enable Tehran to balance its foreign affairs. Entrenched Persian interests as well as the British and Russians, however, conspired to oust first the Belgian experts and then their American replacements.

That Iranians once embraced the United States because Iranian leaders believed Washington disinterested in their affairs may seem quaint given subsequent bilateral relations. It was during World War II that the United States became involved in Iran in earnest, even occupying and helping run a supply route through Persia to the Soviet Union. While many pundits blame the 1953 coup against Mohammad Mosaddegh for the break between the United States and Iran, this is inaccurate. At the time, the United States and many Iranians viewed the episode as a countercoup since it was Mosaddegh and not the shah who was failing to abide by the constitution.

Regardless, the idea that U.S. actions aggrieved those who now lead the Islamic Republic is nonsense—the clerics, distrustful of Mosaddegh’s flirtation with the communist Tudeh party—backed the prime minister’s ouster. The real root of Iranian anti-Americanism began the following decade: American businesses flooded into Iran. The shah’s government granted each immunity so that Iranian courts could not try Americans. If an American employee of Bell Helicopter, Pepsi, or Ross Perot’s EDS got into an automobile accident and killed an Iranian, the Iranian had no recourse, even if the American was drunk and at fault. As such episodes grew, so too did resentment toward Americans and foreign businessmen.

This resentment helped fuel intellectuals at the time who spoke about “Westoxification” and ultimately helped glue together Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s revolutionary coalition of nationalists, leftists, and religious conservatives under the slogan “Neither East nor West but Islamic Republic.” Such distrust is deep-rooted: Tehran and Moscow have had a sustained rapprochement for the past 15 years; officially, relations are at their warmest in 500 years. Five years ago, I did a deep dive for the U.S. Army’s Foreign Military Studies Office into Russo-Iranian relations from Persian language sources to explore Iranian perspectives. What came through clearly was that the Iranian public was much more reticent to re-engage with Russia than was the Iranian leadership. Iranian historical memory is long.

Just as entrenched interests stymied Iranian financial reform in the early twentieth century, so too has the fundamental corruption of the Islamic Republic’s elites undercut Iran’s economy today. Both Revolutionary Foundations (bonyads) and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ economic wing operate above the law. Iran’s shifting power centers and politicized judiciary mean that there is little enforcement in commercial law. While many pundits—especially those who view Iran through the spectrum of American political debates—blame sanctions for Iran’s poor economic performance, those doing business with Iran and Iranians themselves understand that it is Iran’s poor business community and the regime’s economic mismanagement more than any outside power that is responsible for the Islamic Republic’s economic failures.

Back to the current China-Iran deal. China does not have the historical baggage in Iran that the United Kingdom, Russia, or the United States do, but it is also not a state viewed particularly well by many Iranians (unlike Japan for reasons dating back to the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War). Should China move forward with its Iran dealing, it can pursue three different routes: The first would be to allow its businessmen wide freedom during their Iranian sojourn. Cultural misunderstandings and simple accidents, however, can put Chinese citizens on the wrong side of Iranian law. In such a case, Beijing would likely demand immunity, repeating the pattern which soiled U.S.-Iranian ties.

Alternatively, China could treat Iran like its sub-Saharan African investments: Import workers, house them in compounds, minimize interaction, and send wealth back to China. This strategy, however, would only fuel Iranian memories of previous British attempts to dominate Iranian industry. In all likelihood, China will instead take a go-slow approach. The Chinese are not stupid, and they realize Iran’s shifting power centers make business easier said than done, all the more so when any meaningful Chinese investment would undermine the Revolutionary Guards’ own business interests. This scenario too does not end well for either regime as lack of meaningful progress will fuel Iranian resentment toward both their own government and China’s.

Iranian leaders have lost touch with their public. They may look at their China embrace as a way to stick a thumb in the American eye, but ordinary Iranians do not see the United States as the problem, but rather their own regime’s reactionary policies. To believe that their own anti-Americanism justifies a wholesale lease of Iranian sovereignty is a tremendous miscalculation, one that will only further Iranian antipathy toward their own government. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has, in effect, become the new Nasir al-Din Shah.

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, Michael Rubin is a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI).