A famous comedian, now canceled so shall remain nameless, had a standup routine in which he would describe the onboard behavior of airline passengers in the U.S. while comparing them to their great grandparents who probably spent months traversing the same route across the plains beneath in a wagon over a century before, leaving several dead along the way. He would mimic the low sighs of exasperation he’d hear when a new WiFi service didn’t quite work as well as expected and instead came with some annoying buffering, then he would declaim on stage his inner dialogue which was an incredulous and pained ‘YOU’RE IN A CHAIR, IN THE SKY!!’

His point, of course, concerned the speed at which we take new technologies for granted. No sooner have we invented some remarkable new machine than conference papers, followed by whole books, appear arguing that this will lead to a disaster of one kind or another, or wouldn’t have been necessary had it not been for some earlier disaster. For anyone around the age of 50, this can all be a bit mystifying, given how much has changed since the 1970s, but it does nevertheless sometimes take effort to be optimistic, to welcome advances for their own sake, rather than immediately move on to the next bout of techno-foreboding. Maybe that’s the true influence of Twitter; there’s never time to celebrate the good news before the deflating memes appear to ruin it for everyone with a sour joke.

The 1970s were a comparatively innocent age, but I still remember being pleased about the Moon landings for well over a decade and a half, and thinking the U.S. was the greatest country on earth quite unashamedly until about the 1990s. Now SpaceX simultaneously lands two booster rockets on floating barges in the sea, and the overwhelming reaction is ‘Pfffft! That idiot bought Bitcoin!’ A year ago, as the world descended into fearful lockdown, we were solemnly told that no vaccine had ever gone from invention to distribution in less than five years. There were, of course, reasons to be optimistic this time, but public figures were openly and widely censured for saying so. Yet now there are four, with more on the way, so obviously, recriminations and bitter accusations are the order of the day. When I wake up in the morning and turn Twitter on, my presiding curiosity is ‘whose fault is it now?’

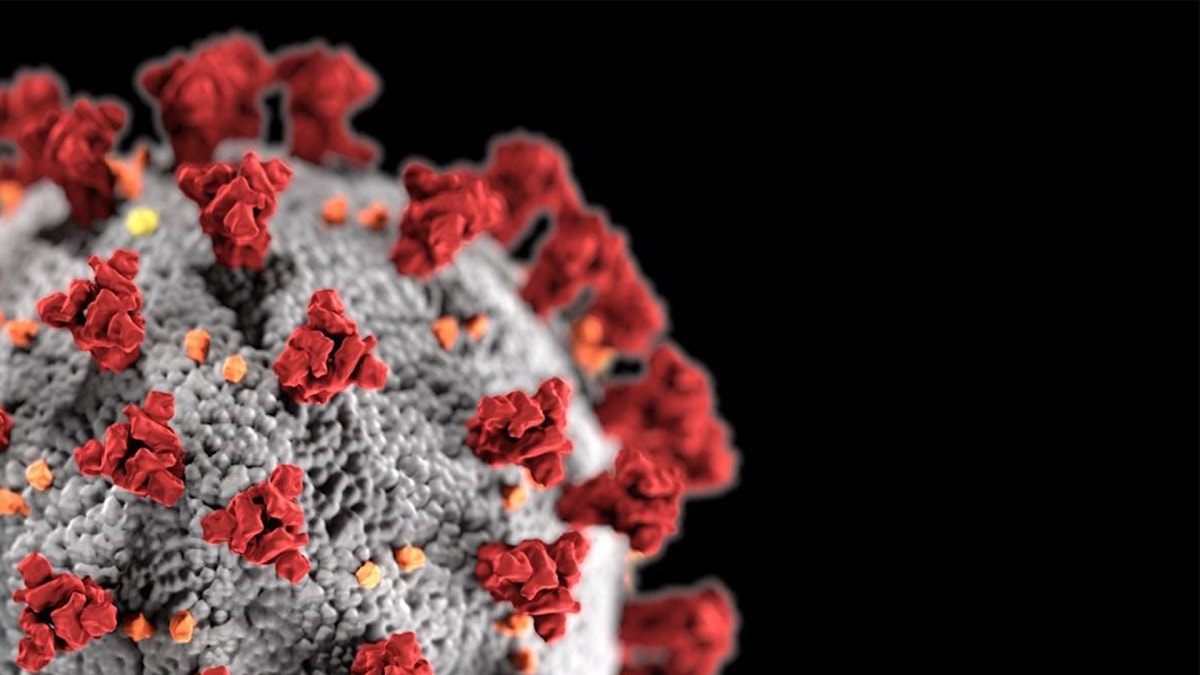

Vaccine Irrationalism

The extraordinary thing about the current mood is that there is much to celebrate. A new and dangerous disease emerged just over a year ago, and Western technology now has it by the throat. Yet despite this, every newspaper in the world is filled with blame for one thing and another. Not only this, the consequent economic downturn has transformed the blame game into a free for, with social stability under strain in some places. What would our wagon train ancestors make of it? My own blitz surviving mother is rather unimpressed, for sure.

The announcement of approvals for the different vaccines has been met with suspicion more than celebration. Inevitable supply constraints have been heavily politicized, despite, though perhaps in part because of, the fastest development and rollout in history. The researchers who developed the (Pfizer) BioNTech vaccine have been rightly lauded, though even this has often taken the form of reproach, with their ethnicity seemingly their most important quality, rather than their expertise. Some, of course, labor to explain that these vaccines were produced by ‘globalization’ rather than science lest anyone think a single nation should ever take any credit for anything. Nor do you need to search hard to find articles reminding everyone that the companies producing these drugs are ‘profit making’, therefore somehow déclassé.

No doubt as the countries that have progressed the furthest along the vaccination route start to open up more minor flaws and annoyances will be pounced upon, but as long as the vaccines work, normal life will resume step by step. Yet, there remains an optimism deficit in the news coverage, along with the ever repeated sense that we must ‘learn from this, and ‘never let it happen again’ which we hear after every single knockback, natural or man-made. It is almost as if the emergence of the vaccines has sharpened awareness of inequality, and therefore raised the appeals for ‘fairness’, or in voguish terminology ‘equity’. But it remains a fact that only some countries can produce working vaccines, most cannot. And if being first is a problem, then no vaccines at all solve that most effectively.

Secondary Effects

Along with all the developments in our understanding of COVID and the remarkable emergence of so many effective vaccines, have come other advances. The mRNA technology used in the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines is radically new and heralds great advances for the prevention and treatment of other diseases. Lost in the relentless focus on COVID were stories that would have made headlines any other time. BioNTech has concluded a test that showed startling success in treating Multiple Sclerosis in mice, and similar technology has made important breakthroughs in a potential vaccine for malaria. These treatments are at an early stage in the research so no champagne corks yet, but malaria affects an estimated 229 million people a year, killing over 400,000, mostly children, in the developing world. For those affected by these diseases, hope is palpable.

Needless to say, the announcement about the potential malaria treatment was met with instant opinions that unless it was delivered with some attention paid to ‘vaccine equity’ it would not be successful. No mention of the billions in Western development funds that have been spent on malaria research over the decades, nor their prime role in funding the WHO. Indeed, malaria is a disease that still exists primarily in the developing world, so the fact that there are any funds at all dedicated to its eradication indicates that Western donors are already working hard on the problem, and always have been.

All of which hints at a broader problem. There is no delicate way to put this but technological progress depends upon inequality. You might even argue that technological progress is the cause of inequality in some respects. The invention is premised on a concentration of capital and innovation that is best nurtured in advanced, developed societies in which said invention stands a chance at generating a return. When threatened, advanced societies use every resource at their disposal to defend themselves and their people, this war is accompanied by huge strides in technological capabilities that then transform societies afterwards. WWII spawned the jet engine, the space program, and the consumerist age of endless cars and household devices from factories that had previously built aircraft and tanks. The Cold War birthed the internet, the communications revolution, and satellite navigation. The struggle against COVID has brought rapid advances in medical treatments, but also in the techniques and technology of disease control, where East Asia already had something of a head start due to SARS. But now that vaccines are finally making solid progress, and to the embarrassment of aspirant states like China and the EU, the innovation states of the UK, the US, and Israel are way out in the lead. Hence the calls for ‘equity’ and ‘fairness’, most loudly from China and the EU.

Winners At Least Imply Winning

China, for its part, has published lurid cartoons in their leading dailies, implying Western states are hoarding vaccines and unfairly forcing the rest of the world to get by with crumbs. This is despite China advertising the effectiveness of two of their own vaccines while refusing to publish the data in support of their assertions. The EU, on the other hand, despite hosting the development of the first approved vaccine, collectivized procurement in such a way as to leave them at the back of the queue. They are now threatening to restrict exports through executive action, despite lauding themselves as a ‘rules-based organization’, such is the emergency they face.

The competition for vaccines, however, is itself remarkable. Had there been only one successful vaccine developed so far, the focus would be on spreading production as widely and quickly as possible. Most people would understand that delays were inevitable. But because there are four, with more to come, there is an unseemly scramble for the most effective ones and the earliest production available. It is because the technological achievement has been so extraordinary and so widespread, that waiting now seems like an intolerable indignity. The sort of fate only the poorest states ordinarily face. This is perhaps especially so given the almost unprecedented levels of criticism sustained by the US and the UK since the advent of the disease. The thought that the early laggards are now streaking ahead has been a bitter pill for some to swallow. Moreover, the resounding confirmation that the cheap and convenient Astra Zeneca vaccine is safe after rumored doubts were broadcast by EU leaders, will signal a huge expansion of its global impact.

If no vaccine had been yet approved, the whole world would remain in varying states of lockdown as the now emerging ‘Third Wave’ spreads from one unvaccinated state to another. Instead, the debate has shifted to the question of distribution and fairness. Why should, it is asked, the rich and developed states have the first claim on the vaccines? Historically, such a question would answer itself, but there are those who seriously argue that the accident of birth should not dictate access to health, never mind the generations of investment in technology and institutions that have made the vaccines possible in the first place. Needless to say, no state has yet prioritized foreigners over their own citizens, and such appeals to do so will no doubt fall on deaf ears. Not least because all advanced states are already doing a great deal to spread access to the vaccine as soon as they can, as they always do. It’s just a question of timing.

Speed vs. Timing

When a pandemic emerges, it is inevitable states will prioritize, within limits, the protection of their own citizens. Their leaders would be considered politically derelict if they did not. But what amounts to a fear of bad timing may also be a great spur to speed. It means that all capable states must make preparations, knowing that they cannot, ultimately, rely on others at the very worst moments of spreading disease. Taken to extremes this need for unilateral capability will produce inefficiencies and duplication, which in turn, will lead to the kind of spare capacity that comes in useful in an emergency.

In this pandemic in the UK we’re fortunate that all of their vaccine investments appear to have been successful, giving them a huge surplus of incoming jabs. But early on they were caught short by overreliance on supplies of imported PPE. They won’t make that mistake again. The surplus vaccines will inevitably be used in large part to vaccinate the populations of other countries who by rights should consider themselves fortunate that the technological sophistication of US, UK, and EU pharma companies, and research base proved adequate to the task, this time. They may need to wait a bit, but at no time in history will the wait have been so short.

For all the talk, therefore, of vaccine equity, competition is intrinsic to progress. Without competition, there would be no progress. And no vaccines at all. And when criticizing rich western states for prioritizing their own citizens, it might be worth remembering that frustration at the failing WiFi in the transcontinental aircraft and recalling that, given where we were just a year ago, ‘YOU’RE IN A CHAIR, IN THE SKY!!’ and with a little luck we’ll be landing soon.