Iranian Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi’s election victory is now president-elect, confirming a rise years in the making.

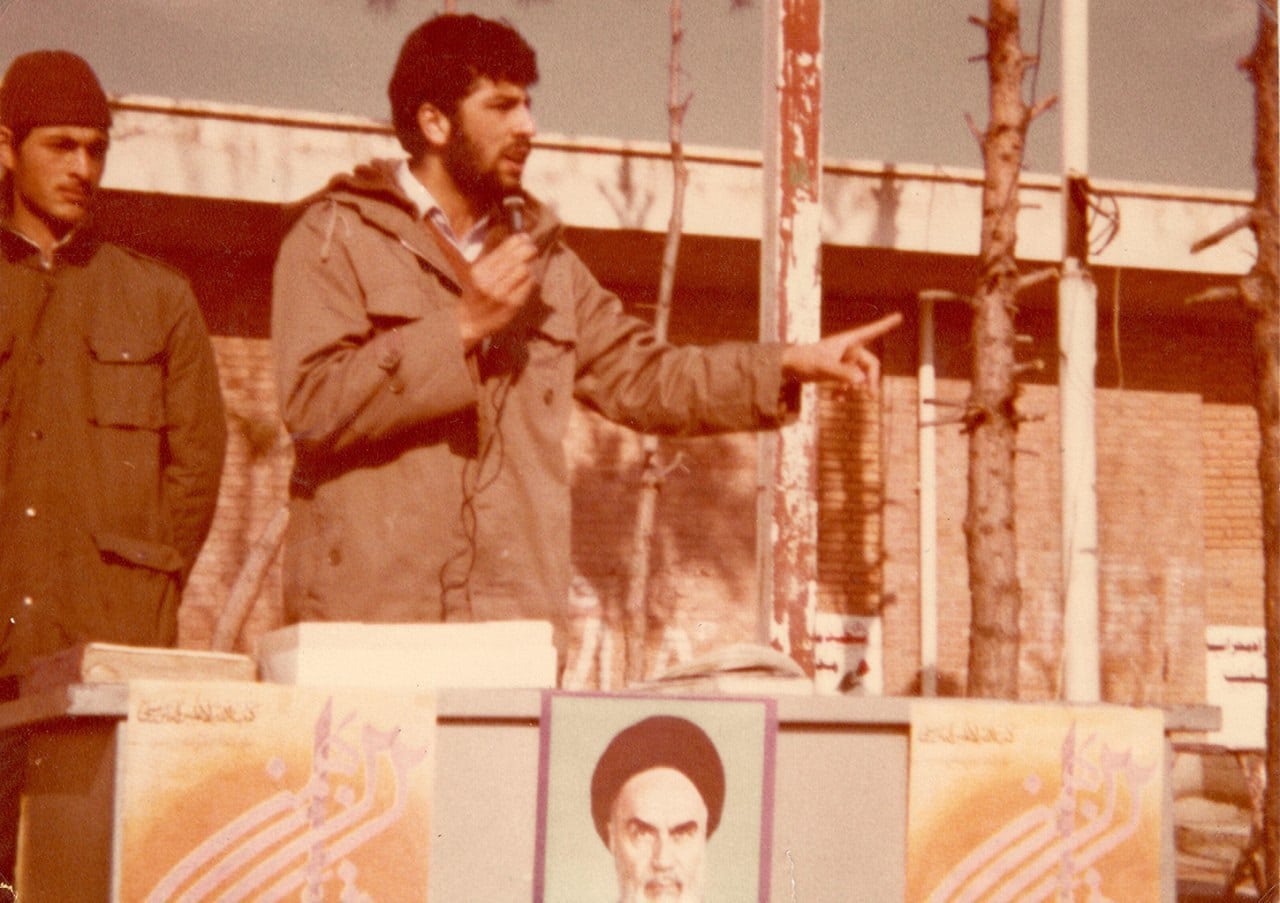

There is much to fear about Raisi. He makes most Iranian revolutionaries appear, by comparison, like Berkeley liberals. Thirty-three years ago, he laughed while condemning dissidents to death. Time has not softened the ayatollah. An Iraqi who heard Raisi speak last February at an event at Iran’s embassy in Baghdad described the experience like listening to a firebrand Bolshevik Revolutionary in early 1920s Moscow.

Raisi truly does not represent the Islamic Republic many news organizations and analysts opined. The Washington Post described the outcome as “predetermined.” So too did Adam Schiff, chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. The State Department spokesman, meanwhile, noted that the United States saw the elections as neither free nor fair. They are, of course, all correct.

In 2009, also, many observers noted the fraudulence of Iran’s elections when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won re-election. Again, they were right. Iranians took to the streets but then as now, senior White House aides subordinated the Iranian desire for democracy to the politics and perks associated with high profile diplomacy.

Few diplomats and pundits, however, pointed out Iran’s election fraud in 1997 when Mohammad Khatami, a so-called “reformist” and former culture minister, won or in 2013 when Hassan Rouhani, a former secretary of the Supreme National Security Council and the regime’s long-time “Mr. Fix-It” took home the prize.

Were those elections more legitimate? Did something in the system change? The answer is no. In every case, the Guardian Council eliminated more than 90 percent of the candidates. Vote-counting was opaque. Western journalists and analysts take Iranian statistics at face-value and accept restrictions on from where they can report if they are granted access to visas at all. To report from central or northern Tehran about what might be transpiring in Sistan, Khuzestan, or Kordestan is akin to sitting in the Upper West Side of Manhattan to explain what voters in Arkansas, Utah, or Maine might believe. Anecdotally, however, voter participation was little more than 10 or 15 percent in Iran’s periphery, and even that figure did not account for spoiled ballots.

The goal of Iranian elections has never been to reflect the popular will, but rather as a means for the supreme leader to flush the system in order to prevent anyone from becoming ensconced enough to threaten him. Khatami’s main function was never reform—after all, as culture minister, he was involved in the same massacre for which Raisi now finds himself castigated—but rather to undermine predecessor Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani’s aspirations. Khatami was a master orator and the passions he unleashed almost spun out of control. He threw these followers under the bus—I was in Iran during the 1999 unrest and watched the movement deflate as Khatami refused to stand up for the protestors—and so won a second term.

Ahmadinejad’s rise, however, was never about an embrace of his conspiracy theory-driven principalism, but rather a desire to rid the regime of Khatami’s allies. Ahmadinejad privileged the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps to the point where his cabinet only had one cleric. The purpose of Rouhani’s election was to cut that organization’s political influence down to size. Rather than push reform, he essentially privileged the intelligence ministry, presiding over what at best was a KGB cabinet.

By projecting faith in reformers and moderates simply because of their more mild rhetoric, the United States does not only itself but also all Iranians a disservice.

First, wishful thinking leads diplomats into traps. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan is only the latest manifestation of the phenomenon. Rafsanjani was the father of the post-Islamic Revolution quest for a nuclear weapon, and much of Iran’s enrichment, covert nuclear warhead, and ballistic missile program developed under Khatami. Diplomats may hand-wring over the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, but President Donald Trump’s rejection of the agreement did not absolve Iran of its commitments under its Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Safeguards Agreement that Rouhani’s Iran is again in violation.

Second, ascribing legitimacy to the system only when the outcome appears amenable to U.S. desires undermines America’s moral authority and falsely enhances the Islamic Republic’s. If diplomats are truly interested in free-and-fair elections, they should deny the supreme leader the legitimacy he so desperately seeks for his revolutionary regime. They should cease pretending the regime’s manufactured elections represent the will of the vast majority of Iranians and cease accepting any statistic not verified by independent observers. Election fraud is not new in the Islamic Republic. It is inherent in the system. It is time to stop pretending otherwise.

Michael Rubin is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a 19FortyFive Contributing Editor.