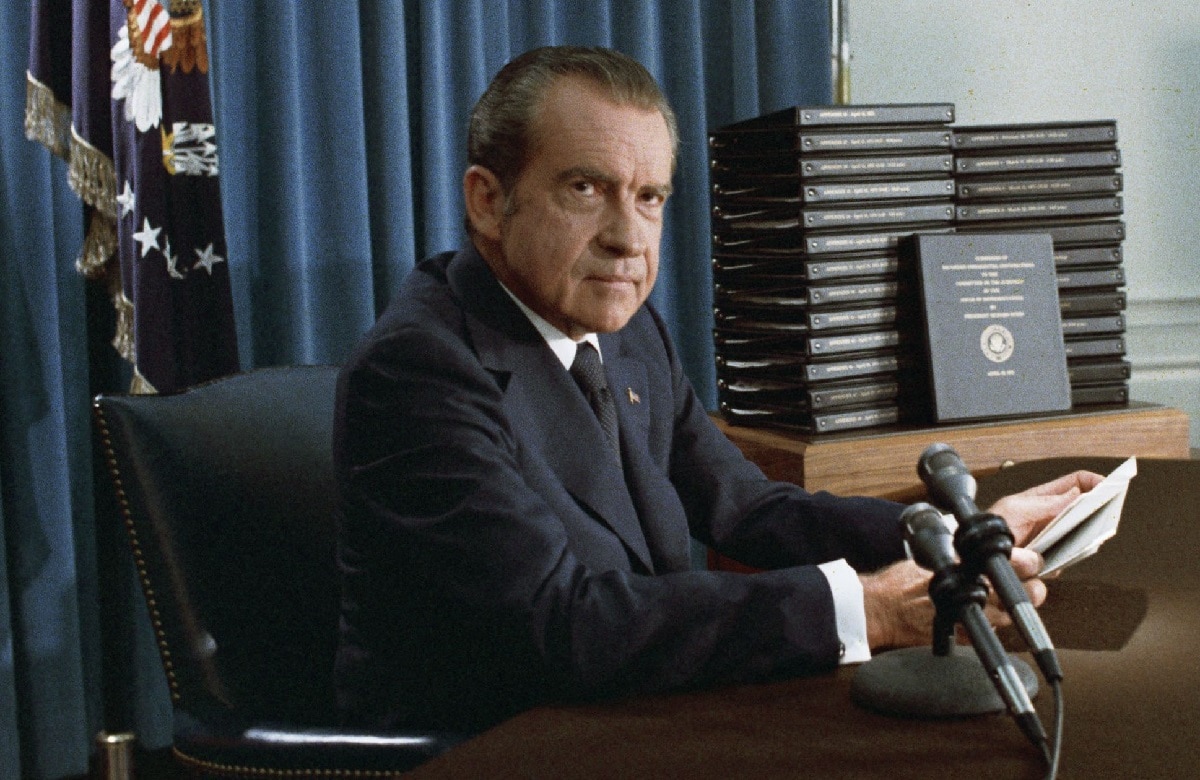

On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon went on television and announced a three‐part New Economic Policy supposedly intended to stop inflation and increase economic growth. By executive order he would “close the gold window,” thus preventing foreign nations from exchanging U.S. dollars for U.S. gold; impose a 10 percent surcharge on imports; and order a freeze on wages and prices. Public reaction was good, and the Dow Jones Average rose the next day. The New York Times editorialized that “we unhesitatingly applaud the boldness with which the President has moved on all economic fronts.”

The few libertarians at the time had a different reaction. Milton Friedman wrote in his Newsweek column that the price controls “will end as all previous attempts to freeze prices and wages have ended, from the time of the Roman emperor Diocletian to the present, in utter failure.” Ayn Rand gave a lecture about the program titled “The Moratorium on Brains” and denounced it in her newsletter. Alan Reynolds, now a Cato senior fellow, wrote in National Review that wage and price controls were “tyranny … necessarily selective and discriminatory” and unworkable. Murray Rothbard declared in the New York Times that on August 15 “fascism came to America” and that the promise to control prices was “a fraud and a hoax” given that it was accompanied by a tariff increase.

Some libertarians who were gathered that night at the Denver home of David and Sue Nolan decided that Nixon’s announcement was the last straw: it was time to form a new political party. In meetings over the next 10 months they created the Libertarian Party and nominated a presidential ticket. One of the attendees at the first convention, in June 1972, was Ed Clark, a free‐market, antiwar lawyer who had decided to leave the Republican Party after Nixon’s speech. He soon became a member of the fledgling Libertarian Party and in 1980 became its most successful presidential candidate to that date.

Much has been said about the economic effects of the Nixon shock. Lew Lehrman wrote in the Wall Street Journal in 2011, “The “Nixon Shock” was followed by a decade of one of the worst inflations of American history and the most stagnant economy since the Great Depression. The price of gold rose to $800 from $35. The purchasing power of a dollar saved in 1971 under Nixon has today fallen to 18 pennies. Nixon’s new economic policy sowed chaos for a decade.” There were intermittent gasoline shortages and lines until Ronald Reagan removed the price controls on oil. David Stockman told me in 1979, when I was new to the policy world, that closing the gold window had been the worst policy decision since he came to Washington. We’re still paying the price for the unleashing of inflation.

But I suppose there were a couple of positive outcomes from Nixon’s very bad decision: the creation of a stronger libertarian movement, and the fact that nobody has seriously proposed wage and price controls since.

David Boaz is the executive vice president of the Cato Institute and has played a key role in the development of the Cato Institute and the libertarian movement. He is the author of The Libertarian Mind: A Manifesto for Freedom and the editor of The Libertarian Reader.