A historic court decision sheds light on how China has used espionage to gain a military and economic advantage over the US and the rest of the world.

US counterintelligence officials managed to lure Yanjun Xu, a senior Chinese intelligence officer, out of China in 2018 and then get him extradited to the US to stand trial for attempting to steal advanced aircraft-engine technology, which China’s military has struggled to develop.

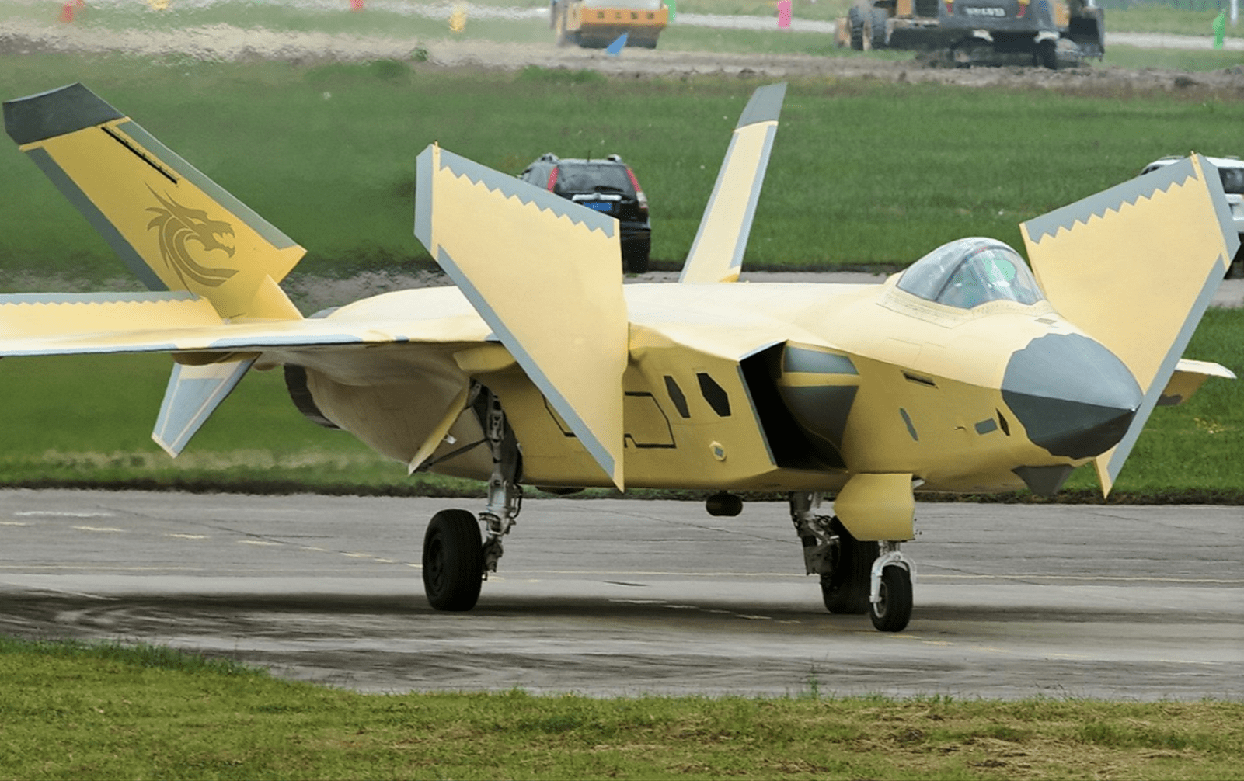

This case is only the latest in a series of espionage operations by Beijing meant to steal industrial and military secrets from the US and its allies and partners and even from Russia — a theft that has allowed China’s military to rapidly build its arsenals of sophisticated weapons.

Common case, uncommon outcome

On November 5, a federal jury convicted Xu — deputy division director of the Sixth Bureau of the Jiangsu Province Ministry of State Security (MSS), the primary intelligence agency of the Chinese Communist Party — of “conspiring to and attempting to commit economic espionage and theft of trade secrets.”

The Chinese intelligence officer was coordinating an operation to get access to a General Electric Aviation composite aircraft engine fan, a piece of technology no other firm has been able to reproduce.

In 2017, David Zheng, a GE Aviation employee, was approached by a Chinese university professor to give a presentation as the Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. The approach was made through LinkedIn, which has become a go-to method for Chinese intelligence to identify foreign targets, including Americans.

Although GE Aviation has strict rules about such presentations, Zheng ignored them and went to China without telling his employer.

During his presentation, Zheng had technical difficulties with his laptop, which contained five GE Aviation training documents. The hosts offered assistance, and a Chinese student inserted a thumb drive into Zheng’s computer — an apparent effort to insert malware or copy the hard drive — and “fixed” the problem.

After the FBI determined that Zheng didn’t willingly turn over any classified information, the GE Aviation employee began cooperating with the agency to lure Xu out of China. In 2018, they succeeded. Xu was arrested in Belgium and became the first Chinese intelligence officer to be extradited to the US.

According to the FBI and Department of Justice, Xu had since 2013 used multiple aliases to target US and third-country aviation companies and experts in that field. He would invite them to China on academic pretexts and then slowly lure them to espionage.

Xu’s arrest and conviction are unique and shed light on a shadowy conflict in which Beijing is trying to wrestle global supremacy from the US using any means possible. Military secrets aren’t the only target. The US’s top counterintelligence agency estimates that Beijing steals $200 billion to $600 billion worth of economic secrets from the US every year.

Alan Kohler, the FBI’s assistant director of counterintelligence, said Xu’s actions were a form of “state-sponsored economic espionage” by the Chinese Communist Party to steal American technological and trade secrets.

“For those who doubt the real goals of the PRC, this should be a wakeup call,” Kohler said. “They are stealing American technology to benefit their economy and military.”

Gaining an edge by other means

China seeks the most advanced tech available, the MSS uses three complementary approaches to steal or otherwise obtain military and industrial secrets.

First, with traditional human intelligence operations that seek to recruit foreign citizens to spy on their countries.

Second, by using non-traditional collectors, such as students or academics, who aren’t intelligence officers but have access to sensitive or classified material through their work.

Finally, the MSS uses cyberattacks to steal foreign countries’ most sensitive and classified industrial, personal, economic, and military material.

Under China’s national security law, every Chinese citizen and firm is obliged to cooperate with the Chinese Communist Party on matters of national security. In practice, that means Chinese companies that do business with foreign firms are required to share any technology or information they acquire with the Chinese military or intelligence services.

Similarly, researchers and postgraduate students working on science, technology, engineering, or mathematics projects are expected to share their research with Beijing.

US companies are always at the top of the target list, but “friendly” countries aren’t safe either.

Earlier this year, it was reported that Rubin Design Bureau, one of Russia’s main submarine designers, was hit by a cyberattack likely done on behalf of China. In 2012, two Russian academics were jailed for passing information on nuclear missiles to Chinese intelligence.

Stavros Atlamazoglou is a defense journalist specializing in special operations, a Hellenic Army veteran (national service with the 575th Marine Battalion and Army HQ), and a Johns Hopkins University graduate. This first appeared in Sandboxx News.