The U.S. Air Force has some pretty impressive fighters in the F-35 and F-22 stealth fighters. And yet, Russia has its own stealth fighters as well as China. That might not matter, as NGAD is coming soon and it could be quite dominant: Recncetly, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall announced that the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program is moving into the next stage of development with the aim of fielding America’s next air superiority fighter by 2030. That’s significantly quicker than most fighter programs, and suggests the effort must be progressing very well.

The NGAD, which will include a crewed fighter as well as drone support aircraft, has now begun its engineering, manufacturing, and development (EMD) program, which will then lead to actual production.

As Howard Altman reported for The Warzone, Kendall noted that the Air Force needs to speed up its processes to get this fighter into the sky. Kendall’s not wrong—on average, it takes the Air Force around seven years from the beginning of the EMD phase to the point an aircraft reaches initial operating capability (IOC).

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, for instance, had its EMD contract awarded in October of 2001, but the F-35B didn’t reach IOC until 2015. The F-35A reached it in 2016 and F-35C didn’t reach initial operating capability until 2019.

This time, however, Kendall wants the Air Force to move straight into development right away, fielding the new family of fighter systems within the next eight years.

“What we tend to do is do a quick demo, and then we have to start an EMD or development program and wait several more years, because we didn’t start the developmental function. If we don’t need it to reduce risk, we should go right to development for production and get there as quickly as we can.”

This push to expedite the NGAD’s development timeline is in keeping with reports that the NGAD effort has been progressing well, with at least one full-sized technology demonstrator taking to the sky in 2020.

“The clock really didn’t start in 2015; it’s starting roughly now,” Kendall said. “We think we’ll have capability by the end of the decade.”

The 2030 timeline also parallels statements made by the Air Force indicating that the F-22 Raptor, America’s current top-tier air superiority fighter, may not be survivable in contested airspace much beyond 2030. Despite boasting what is considered to be the smallest radar cross-section of any stealth fighter, the F-22 is no spring chicken—the aircraft first flew a quarter-century ago.

The Air Force moved to retire nearly 1/5 of its Raptor fleet earlier this year, opting to send its non-combat coded F-22s out to pasture in favor of reallocating the funds toward modernizing the remaining 150 or so stealth jets. The F-22 will likely still outclass any fighter it comes across by 2030, but may not be as survivable against modern integrated air defense systems leveraging approaches like multi-static radar arrays.

Despite widely being recognized as a program aiming to field a new family of fighter systems, to this point, NGAD has actually been an experimental effort, rather than a production-oriented one. In other words, officially speaking, NGAD wasn’t about fielding an operational platform, as much as about testing technologies that could feasibly be incorporated into such a fighter.

“So we basically had an X-plane program, which was designed to reduce the risk in some of the key technologies that we would need for a production program,” Kendall said before adding that he’s, “not interested in demoing experiments unless they are a necessary step on the road to a new capability.”

What do we already know about the NGAD fighter?

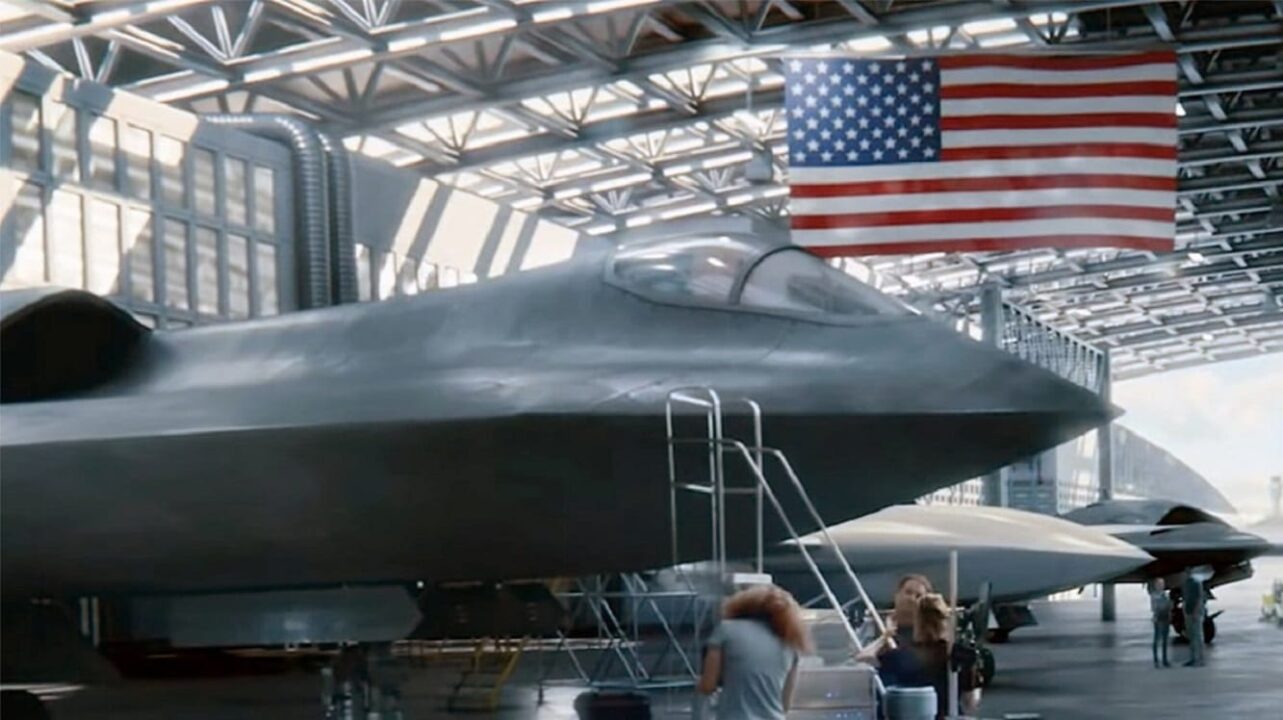

America’s Next Generation Air Dominance, or NGAD, fighter program is continuing to mature behind a veil of classified funding, but tantalizing details about this program have emerged in recent months, bringing some of its groundbreaking aspects into full view. And if what we’ve been hearing about this new family of systems can be believed, the NGAD program will usher in a significant shift in the way America approaches air dominance. In fact, the resulting aircraft might even look more like a bomber than a fighter in some respects.

Late last month, John Tirpak, the editorial director of Air Force Magazine, released a fantastic piece on the NGAD program, summarizing how funding for this new fighter and its support aircraft has increased over time, and offering some of the more reliable rumors to come out of Pentagon and Air Force offices. Between his coverage and other public discussions of this program from the likes of folks like former Air Force acquisition executive Will Roper, it’s beginning to look like the NGAD fighter program is progressing both well… and entirely unlike any fighter acquisition program ever to come before it.

The NGAD won’t replace the F-22 fighter for fighter

The F-22 production line was famously cut short at just 186 delivered airframes out of an initial order of 750 aircraft. And earlier this year, the Air Force proposed retiring 30 of its oldest F-22s (aircraft that were never combat coded and have been used only for training) in order to reallocate their maintenance funding toward updates for the rest of the fleet. With just over 150 F-22s left in service, America’s fleet of 5th generation air superiority fighters is becoming endangered, but if you thought new NGAD fighters would swoop in to fill the gap right away, you’ll likely be mistaken.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing, however. There are a number of reasons why the NGAD fighter program may not produce as many crewed platforms as currently exist in America’s F-22 inventory; chief among them being that the NGAD is expected to fly with a constellation of drone support aircraft. This could allow one crewed NGAD fighter, accompanied by armed-drone wingmen, to fill air superiority roles that would traditionally call for a larger number of crewed fighters. At an anticipated cost per airframe of around $200 million for the piloted NGAD fighter, that model would reduce some of the sticker shock associated with its high acquisition cost.

But there’s another good reason why the NGAD program may not be looking to purchase hundreds of new fighters at the onset of the jet entering operational service.

“The program is both about building a better aircraft, and also about building aircraft better,” Roper said in 2020, adding that the Air Force’s NGAD program is “very close” to developing a new acquisition model for fighter aircraft.

The F-35 is expected to fly for more than 50 years. The NGAD won’t last anything close to that long.

The earliest parts of the Joint Strike Fighter program date all the way back to 1993, with developmental contracts awarded to Lockheed Martin and Boeing in 1996. Lockheed Martin’s X-35 submission was named the victor in October of 2001, with the first F-35 flight tests beginning in 2006 and the Air Force flying its first F-35A in 2010. In 2016, the F-35’s anticipated retirement was pushed back from 2064 to 2070; this will be some 64 years after the aircraft first took flight.

That exorbitantly long shelf life comes thanks to the massive cost of the F-35 program — it simply needs to last a long time in order to justify its expense. But it also comes as a result of the Pentagon’s traditional approach to fighter acquisitions and timelines. As Roper explained on more than one occasion, the Air Force is shifting away from half-century-spanning fighters, and instead toward short production runs of just 50 or 100 airframes expected to remain in service for just 12 to 15 years. That means fresher fighter designs in service, newer technologies being fielded regularly, and importantly for the fiscally minded — a huge reduction in overall program costs.

According to a July 2021 report from the Government Accountability Office, the F-35’s total program costs currently sit at an anticipated $1.3 trillion dollars, but of that figure, less than $400 billion represents the actual cost of procuring the 2,456 stealth fighters Uncle Sam has on order. That means actually buying F-35s only represents about 30 percent of the program’s total cost, with most of the remainder allocated to sustainment over its 50-plus years of service.

The Air Force wants new fighters every 10-15 years

By switching to more frequent fighter development programs, the force can field more advanced fighters, better suited to counter the emerging air defense threats of their day, while dodging the vast majority of the expense associated with these sorts of programs. Initial procurement costs will likely go up in the short term, but by taking a modular approach to both hardware and software architecture, systems that are not being replaced or updated can simply be migrated to the next fighter in development. This will dramatically reduce the time and costs associated with the research and development of each aircraft.

But this move isn’t just about cutting costs. The United States maintained a monopoly on operational stealth aircraft technology from 1983, when the F-117 Nighthawk first entered service in secret, all the way until 2017 when China’s Chengdu J-20 entered service. That three-decade lead has paid dividends, with America’s stealth aircraft still considered to be significantly more difficult to detect than Russian or even Chinese entries. But now that these nations are operating stealth platforms of their own, maintaining that edge will prove more difficult.

Not only are these nations rapidly developing new stealth aircraft designs, but they’re also developing tactics and technologies meant specifically to counter America’s stealth advantage, using their own platforms to achieve that. New integrated air defense systems sporting multi-static radar arrays, finely tuned low-band radar systems paired with infrared detection systems, and constantly improving surface-to-air missile technology all pose growing threats to America’s stealth fleets. The F-35, sporting a stealth design that was largely finalized in the1990s, might be extremely tough to detect in 2022, but it seems unlikely that its stealth will remain as effective in the 2060s.

By swapping modular systems into improved designs, firms that are competing every five to ten years for new fighter contracts can leverage the latest electronic warfare systems, the most advanced production materials, and the latest design elements to combat detection from the systems in service and on the horizon today, rather than expecting today’s technology to withstand five decades worth of enemy advancements.

It won’t be a banner program for one firm like Lockheed Martin’s F-35 or Northrop Grumman’s B-21

Lockheed Martin’s winner-take-all victory over Boeing for the Joint Strike Fighter contract granted it not only funding for the continued development of the fighter, but also the production of the jet, and then sustainment for as long as the aircraft is in service. This gave Lockheed a great deal of leverage over establishing costs, and also left America’s other primary fighter contractors with little reason to continue research and development on advanced fighter designs. After all, with more than 2,000 F-35s on order, there was little reason for other big firms to keep working on fighter technology.

According to Will Roper, that is not how NGAD procurement will go. The Air Force has already split NGAD into three separate contracts: one for design, one for production, and one for sustainment. As a result, firms now not only have to compete to field the best fighter, but they must also compete to see who can build them most efficiently, as well as who can maintain them in the most cost-effective manner. This will allow smaller firms to get into the fight—as only a handful of companies in the nation have the infrastructure needed to design, produce, and maintain a fleet of advanced jets. Now, firms that specialize in design can compete for one contract, while firms that may specialize in sustainment can compete for another.

In the years to come, we may see new companies become rockstars in these individual spaces, as small firms with big ideas get the opportunity to gain a foothold in the American fighter market. It’s entirely feasible that we could see a winning NGAD design come from a company few outside of the defense space have ever even heard of. And that winning design may ultimately see production from a more established firm like Lockheed Martin, and then sustainment managed by yet another party.

In other words, NGAD could go on for decades, with a whole series of different fighters being churned out as the Air Force crams new modular systems into the fuselages of the latest and greatest designs that the industry’s best minds have to offer.

The NGAD fighter might be a lot bigger and heavier than you’d think

In October of 2020, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) released a report on the NGAD fighter program that included a lot of the information we’ve all become familiar with over the past few years, but one particular portion stands out as something few have discussed since:

“There appears little reason to assume that NGAD is going to yield a plane the size that one person sits in, and that goes out and dogfights kinetically, trying to outturn another plane—or that sensors and weapons have to be on the same aircraft,” the report stated.

The NGAD fighter program has been tasked with assuring American air dominance over 21st-century battlefields, but that doesn’t mean it has to do it in the ways we’ve come to expect of a fighter. Over the past few decades, there has been a growing sentiment within the American defense apparatus that the days of aerobatic dogfighting in close quarters have come to an end, thanks to advanced sensors and highly capable long-range air-to-air weapon systems. Whether or not this is true is subject to a great deal of debate, but there’s reason to believe the Air Force may adopt this line of thinking for the NGAD program.

America’s new “fighter” could actually be more of a “mother ship,” tasking highly capable drone wingmen with various objectives and building upon the F-35’s “quarterback in the sky” mentality, rather than F-22’s dogfighting dominance.

The CRS report conspicuously leaves room for this interpretation of the NGAD fighter’s mission.

“For example, a larger aircraft the size of a B-21 may not maneuver like a fighter. But that large an aircraft carrying a directed energy weapon, with multiple engines making substantial electrical power for that weapon, could ensure that no enemy flies in a large amount of airspace. That is air dominance,” the reports adds.

This assertion, made in 2020, might be predicated on statements made by the former commander of Air Combat Command, Gen. Herbert “Hawk” Carlisle, in 2017 about a precursor program to NGAD known as the “Penetrating Combat Aircraft.” As reported by Air Force Magazine at the time, Carlisle suggested America’s next fighter might have a need for more substantial weapons capacity, fuel range, and low observability to radar, saying it may be more like the “B-21 bomber” than the F-22.

The B-21 and its predecessor, the B-2 Spirit, both utilize flying-wing designs that are difficult to detect even on the lower-frequency radar bands that can currently spot (though not target) America’s stealth fighters. These designs, however, tend not to offer the same degree of maneuverability you can get from modern fighters.

“It may be bigger than we think,” General Carlisle said. “Maneuverability is one of those discussions — as in, if it’s penetrating, what level of maneuverability does it need? We don’t know the answer to that yet.”

Lest you think these are simply outdated statements, Lt. Gen. David S. Nahom, deputy chief of staff for plans and programs, seemed to echo this sentiment in March of this year, when he stated clearly that the Air Force is developing this fighter with extremely long ranges in mind.

“We’ve never developed a fighter with the ranges of the Pacific in mind before,” he said. “So this would be a first.”

Despite the possibility that the NGAD fighter may be much larger than we’ve come to expect of air superiority fighters, it’s still expected to be a high performer. John Tirpak speculates that the NGAD will be able to fly at least as high and as fast as the F-22, meaning a service ceiling as high as 70,000 feet and a top speed potentially as high as Mach 2.8. That idea may be backed up by Will Roper, who told the media the NGAD fighter’s flown full-sized technology demonstrator had already “broken a lot of records.”

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran who specializes in foreign policy and defense technology analysis. He holds a master’s degree in Communications from Southern New Hampshire University, as well as a bachelor’s degree in Corporate and Organizational Communications from Framingham State University. This first appeared in Sandboxx News.