The U.S. military is always looking for new and daring ways to bring more firepower onto the battlefield of tomorrow. And the idea of a Rapid Dragon arsenal ship weapon has been kicked around for a few years. How close is it to reality? This expert and former U.S. Marine has some ideas: Increasingly capable long-range air-launched munitions have already granted new life to elder statesmen like the B-52 Stratofortress, but the Air Force’s Rapid Dragon program aims to take this concept to the next level. Rather than relying solely on heavy payload bombers and strike fighters to deliver stand-off munitions, Rapid Dragon will allow America’s large fleets of cargo aircraft to join the fight as missile-packing arsenal ships. In fact, this system could even turn cargo aircraft into incredibly potent warship hunters if a conflict were ever to break out over the Pacific.

It may seem counter-intuitive to fly massive radar-reflecting platforms like the C-130 Hercules or C-17 Globemaster anywhere near contested airspace in order to deploy munitions, but the premise behind Rapid Dragon isn’t to send these hulking airframes into the fight. Instead, the effort leverages palletized standoff weapons like the AGM-158 JASSM (Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile) with ranges that can exceed 1,000 miles—allowing the cargo aircraft to deploy its ordnance from well beyond the reach of enemy air defenses. According to the Air Force, this would allow them to saturate enemy airspace with a large volume of low-observable cruise missiles for a relatively low cost and low risk.

The name “Rapid Dragon” is actually an homage to an ancient Chinese siege weapon that saw use around 950 AD called “Ji Long Che” — which translates to “Rapid Dragon Carts.” These weapons were effectively crossbow catapults that allowed a single user to pull one trigger to launch as many as 12 arrows simultaneously at long distances for the day.

As the Air Force Research Laboratory puts it:

“Today, the Rapid Dragon concept is changing the game again, this time as an airborne delivery system for U.S. Air Force weapons. And like its namesake, these palletized munitions promise to unleash mighty salvos en masse on distant adversaries.”

Somewhat ironically, the Rapid Dragon weapon system may prove most valuable in a conflict against the nation from which it draws its name. Thanks to low-observable and long-range munitions like the JASSM family of cruise missiles, these cargo aircraft could saturate enemy airspace with missiles, take out whole fleets of enemy ships, or lay mines across vast expanses of the ocean—all without coming to within range of Chinese air defense systems.

Using cargo planes to ferry missiles into the fight isn’t a new concept

The underlying concept behind using America’s existing commercial and cargo aircraft to ferry and launch missiles has been around for some time, but saw particular interest in the 1970s. In the early part of the decade, Henry Kissenger’s efforts to re-gain the nuclear upper hand over the Soviet Union prior to entering strategic arms reduction talks led to the Air Mobile Feasibility Demonstration program. Benign as that title might seem… the effort was anything but.

Over just 90s days in 1974, the program proved that the United States could actually launch a 57-foot, 87,000-pound LGM-30 Minuteman 1 nuclear ICBM out the back of an airborne C-5 cargo aircraft from practically anywhere. The fast-paced program culminated in a live-fire demonstration of an inert ICBM, but after proving this unusual method of deployment was not only possible, it was downright feasible, the United States opted to shelf the capability.

Mutually Assured Destruction is often cited as the driving force behind the U.S. and Soviet Union matching capabilities, but a few programs, like the Air Mobile Feasibility Demonstration program, represent the opposite side of the same coin. Programs like it—and the nuclear-powered SLAM missile—ultimately saw cancellation or indefinite pauses either to prevent the Soviet Union from pursuing the same technology or out of concern that it created a potent enough advantage that it might prompt them to launch a nuclear first strike just to prevent the advantage from being leveraged.

The concept of using cargo aircraft to deploy missiles emerged once again in the late 1970s after the Carter administration announced the cancellation of the supersonic heavy-payload B-1B bomber program. With the B-2 being developed being a veil of classified funding, the United States appeared to be cruising toward a gap in its ability to deliver ordnance by air, resulting in a proposal to use Boeing’s 747-200C as an arsenal ship packed to the gills with AGM-86 air-launched cruise missiles.

The long-serving B-52 Stratofortress was able to carry around 20 of these 1,500-mile-range missiles, but the proposed 747 CMCA (Cruise Missile Carrier Aircraft) would have flown with a whopping 72 onboard. The weapons would have pre-programmed target data that could be adjusted from within the onboard command center, and would be launched one at a time in rapid succession from a door near the tail of the aircraft.

Because of the existing global infrastructure for the operation of 747s already in place and a production line already in operation, this effort seemed both promising and cost-effective. The 747 CMCA could carry nearly three times the cruise missiles of a B-52 at nearly 1/3 the price per flight hour. Ultimately, the B-1B Lancer would be brought back from the dead instead, with the B-2 Spirit following closely behind.

Rapid Dragon turns cargo planes into arsenal ships (without modifying the cargo plane)

The Rapid Dragon concept isn’t entirely dissimilar from the 747 CMCA in a number of important ways. Like the CMCA program, Rapid Dragon aims to use long-range air-launched cruise missiles to keep the vulnerable arsenal ship out of harm’s way. Its cruise missiles are also brought aboard with target data already plugged in, but as demonstrated in a flight test late last year, that target data can be changed by the crew on board the aircraft mid-flight.

But as economically feasible as the 747 CMCA concept may have been, Rapid Dragon takes the financial efficiency of the premise even further.

Rather than customizing specific aircraft for the arsenal ship role, Rapid Dragon uses self-contained palletized munitions called “deployment boxes” that can be loaded aboard any C-130 (in a six-missile magazine) or C-17 (with a nine-missile magazine). These modular deployment boxes allow for the maximum variety in both weapons deployed and space utilized while keeping production costs low.

The deployment boxes are loaded like any other airdrop pallet and then deployed while airborne without the need for any modifications to the aircraft itself, in what the Air Force Research Laboratory calls “roll-on roll-off capability.”

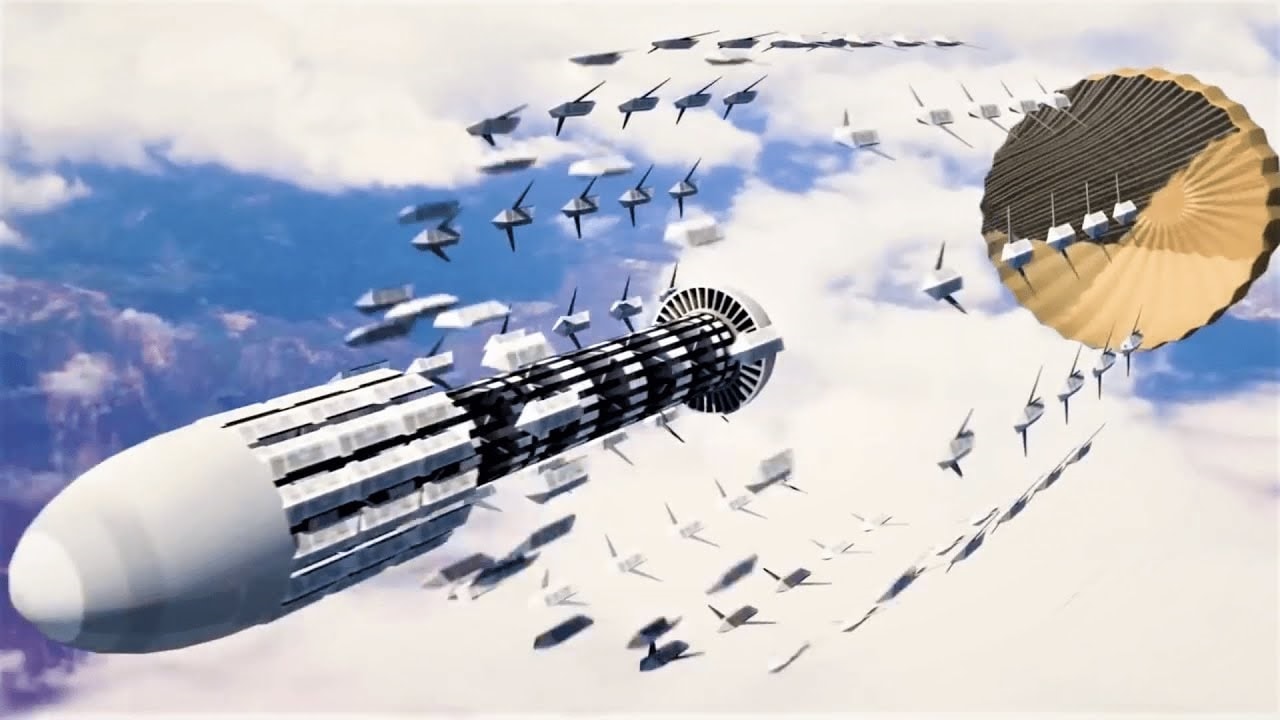

Once the order has been given to deploy the weapons, the crew onboard the cargo aircraft go about their business just like any standard airdrop, with parachutes deploying to orient and stabilize the deployment box for the missiles to launch. Once ready, the onboard control box begins releasing AGM-158 JASSM cruise missiles individually to prevent them from conflicting with one another. Each missile then deploys its small wings and control surfaces, fires up its engines, and pulls up into its traditionally horizontal flight path.

The original AGM-158 JASSM entered service as a 14-foot, 2,251-pound weapon capable of delivering a 1,000-pound warhead to targets some 230 miles away, but by 2006, the Air Force was testing the JASSM-ER, which offered the same external dimensions with a jump in range to 575 miles.

Last year, in 2021, low-rate initial production began on the latest iteration of the cruise missile, known as the AGM-158D JASSM-XR. The XR boasts a range in excess of 1,000 miles, giving the Rapid Dragon concept some serious legs. And to make matters worse for potential targets, these fairly low-cost missiles (at under $2 million each) are considered to be quite stealthy, making them hard to detect and even harder to intercept.

The AGM-158 family also includes the AGM-158C Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), which means Rapid Dragon could turn cargo planes into serious ship-hunting platforms over the vast expanses of the Pacific. In fact, last December, the Air Force announced successfully hitting a “maritime target” with a cruise missile deployed from a C-130 as a part of this same program.

Right now, the Rapid Dragon effort is focused on 6-weapon deployment boxes for the C-130 and 9-weapon boxes for the C-17, but future plans already include expanding both the number and types of weapons employed to allow for greater mission variety. To date, the effort has seen successful tests in three different airframes: the MC-130J, the EC-130SJ, and the C-17A.

As a result of keeping the entire apparatus contained within the deployment box itself, the same C-130 that was ferrying cargo between installations on Monday could feasibly be used to saturate enemy airspace with missiles on Tuesday before returning to its cargo responsibilities on Wednesday.

Rapid Dragon isn’t just about munitions, it’s also about cost

Like the 747 CMCA concept, the premise behind Rapid Dragon would seem to steal some of the thunder from America’s bomber fleets, which might lead some to ask what value there is in developing both the B-21 Raider and the Rapid Dragon capability set. The simple answer is that there’s a great deal of value to be found in having broad capabilities offered by a variety of platforms, giving combatant commanders a slew of options at their disposal regardless of assets in theater. But there are also important considerations about cost and the availability of airframes in a large-scale conflict to consider.

The United States Air Force currently maintains a fleet of around 75 B-52s. These heavy payload bombers fill a variety of roles within America’s force structure—particularly as the conspicuous portion of the airborne leg of the nation’s nuclear triad.

With the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserves included, the Air Force can bring more than 400 C-130s of various types into the fight, along with an additional 220 or so C-17s. So, rather than worrying about fewer than a hundred heavy payload bombers deploying stand-off weapons at targets inside enemy airspace, potential opponents would be looking at literally hundreds of potential deployment systems, each capable of launching a half dozen or more missiles at a time, with existing operational infrastructure all over the world.

And while the B-52 costs somewhere in the neighborhood of $70,000 per hour to fly, the various forms of C-130 largely cost under $10,000 per hour (with a few notable exceptions) and can fly from austere airstrips most bombers would never even consider.

Of course, these munitions could also be launched by other platforms, but that’s part of the value of Rapid Dragon: by leveraging America’s existing fleets of low-operating-cost cargo aircraft for airstrikes, bombers and fighters can be freed up to focus on other high-value operations that might call for their more specialized capability sets.

Of course, the weapons themselves are not inexpensive, at more than $1 million each, but if used to destroy Chinese hypersonic anti-ship missile systems or warships, that cost could really be seen as a significant value.

A plug-and-play capability with far-reaching implications

Rapid Dragon can give the United States a significant boost in its ability to launch cruise missiles at targets inside contested airspace, but its value can be further bolstered by sharing this technology with allies. In fact, expanding ally capability sets may be one of the places where this program shines brightest.

The C-130 is among the most widely operated military aircraft in the world, with more than 2,500 airframes delivered to 63 nations since production began in the 1950s (and at least seven others buying them second-hand). Because the Rapid Dragon deployment boxes are designed to be “roll-on roll-off” with target data that can be either programmed in ahead of time or adjusted on the fly, the United States could provide these systems to allies, converting their own cargo fleets into ship-busting arsenal planes as well.

When considering large-scale warfare in terms of cost, the ability to deploy a large volume of low-observable, long-range cruise missiles into enemy airspace from a wide variety of aircraft is a good thing. But the ability to quickly provide that same capability to allied forces within a region with very little training required and while leveraging their existing aircraft and infrastructure is practically unheard of. In a conflict with China, Japan’s fleet of C-130s could also deploy cruise missiles or even drones alongside American airlift platforms, for instance, further increasing the number of airframes available for the fight and the number of missiles or drones deployed.

These weapons could also be used for electronic warfare and the impression of enemy air defenses. Air defense systems that attempt to intercept the swarm of weapons could be quickly depleted of interceptors, making the airspace safer for all allied aircraft following behind the Rapid Dragon missile avalanche.

That capability becomes all the more pronounced when you consider the use of these systems to deploy a large volume of AGM-158C Long Range Anti-Ship Missiles, which likely offer a range comparable to the JASSM-ER at 575 miles. China’s naval presence in the Pacific is significant, and when considering large militia and Coast Guard vessels as well, outnumbers America’s global Navy by better than 2:1. China’s most advanced long-range air defense systems can’t engage targets beyond 200 miles or so, making a C-130 packed to the gills with 500+ mile LRASMs a serious threat to their naval supremacy in the Pacific.

The LRASM is more expensive than most weapons in the JASSM family at just under $4 million each, which has prompted Chinese analysts to suggest that Rapid Dragon wouldn’t be sustainable as a means of anti-ship warfare. But when considering the cost and time required to replace an advanced warship like China’s Type 055 destroyers, a handful of LRASMs may well be a bargain.

And as long as we’re playing the hypothetical game, it’s worth discussing something legendary Navy Admiral James Flatley told me last year. Flatley is the only man ever to land a C-130 on an aircraft carrier, but he didn’t just do it, he proved it was borderline practical — landing and taking off again from the deck of the USS Forestall dozens of times before the exercise was over.

After publishing a story about the effort, Flatley reached out to me and we spoke at length about his time aboard America’s flattops — and he made it clear that, although using the C-130 to resupply carriers seemed unnecessary at the time, the Navy has kept that capability in its back pocket… just in case some large scale conflict ever provided a good reason to see the mighty Hercules return to the decks of America’s airfields at sea.

Interesting food for thought.

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran who specializes in foreign policy and defense technology analysis. He holds a master’s degree in Communications from Southern New Hampshire University, as well as a bachelor’s degree in Corporate and Organizational Communications from Framingham State University.