What Made the F-16XL Special:

Even though General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon took its first flight nearly 50 years ago, it remains in active duty with the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve Command, and Air National Guard units.

The F-16 has also been adopted by some 25 other nations and is still the world’s most numerous fixed-wing aircraft in military service today.

The compact, multi-role fighter aircraft is highly maneuverable and has proven itself in air-to-air combat and air-to-surface attack.

It continues to provide a relatively low-cost, high-performance weapon system for the United States and allied nations. The F-16 is currently scheduled to remain in service until at least 2025.

However, the Fighting Falcon could have been even better. Thought it was improved as the F-16C and F-16D – the single- and two-place counterparts to the F-16A/B, which incorporate the latest cockpit control and display technology – and later as the Block 60 F-16E/F models designed for use by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), some aviation experts suggest an opportunity was missed.

A New Concept

Meet the F-16XL, which was developed by General Dynamics as a contender for the United States Air Force’s Enhanced Tactical Fighter (ETF) program to replace the F-111 Aardvark. The XL variant was noted for its radically-modified delta wing shape design that more than doubled the area of a standard F-16 wing.

Development of the F-16XL began under the direction of Harry Hillaker, the “Father of the F-16,” as the Supersonic Cruise and Maneuver Prototype (SCAMP), which was designed to highlight how supersonic transport (SST) aerodynamics had a place with military aircraft. A largely theoretical and model-based test study had determined that a cranked arrow wing shape could provide vastly increased lift without any of the limitations that came with a delta wing when paired with an F-15A fuselage.

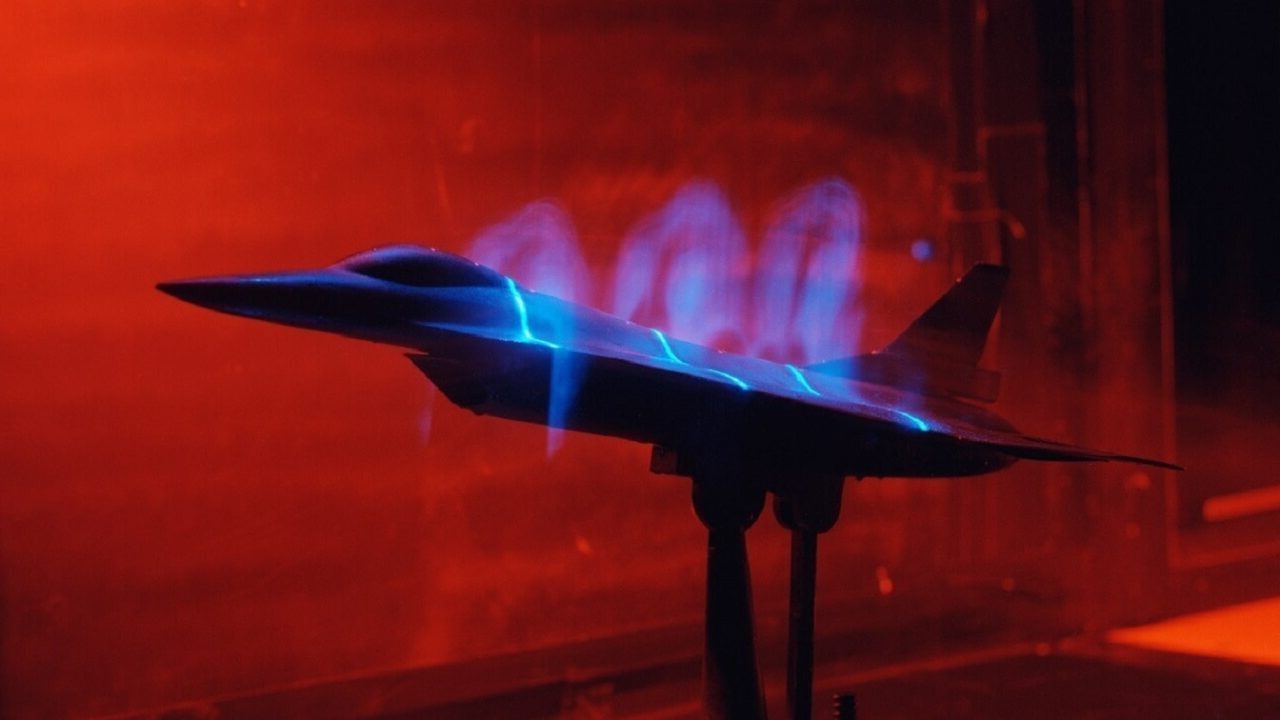

General Dynamics had invested heavily in the research and development of the delta-winged F-16XL, and it partnered with NASA to test more than 150 different configurations. That included some 3,600 hours in NASA wind tunnels.

F-16XL: Two Prototypes

Two prototypes of the delta-winged aircraft were built and each featured a fuselage that was lengthened by 56-inches, while the modified aircraft lacked the ventral fins, which weren’t required due to the delta wing that provided stability characteristics superior to the original F-16. However, despite the fact that the wing was larger and the fuselage length increased, the “XL” was certainly not meant to stand for “extra-large!”

By most accounts, the F-16XL was seen to have all the merits the Air Force could have wanted, and the two prototype aircraft performed admirably in the Air Force’s tests. It was actually concluded that the F-16XL could fly twice as far, or carry twice as large a payload, as a normal F-16. However, the Air Force opted to go in another direction – and chose the McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle instead.

Among the factors cited for the decision was the fact that the F-16XL would have required far more effort, time, and notably more money to put into production – while the Strike Eagle’s two engines meant it had more thrust and the ability to carry more weapons. Moreover, the McDonnell Douglas aircraft was capable of supersonic speeds at high or low altitudes, all while carrying its mighty payload, and had no trouble climbing quickly with bombs underwing.

NASA Research

After the ETF contract was awarded to McDonnell Douglas, the two General Dynamics F-16XL prototypes were placed in storage at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB), Mojave, California. The XL story could have ended at that point, but in 1988, the prototypes were taken out of storage and provided to NASA for further research.

Image: Creative Commons.

Image of what would have been the F-16XL, an artist rendering. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Those received serial numbers #849 and #848, and they were subsequently used in a program designed to evaluate aerodynamics concepts to improve wing airflow during sustained supersonic flight. Each of those aircraft was then used in a variety of experiments that only concluded in 1999. That included a 1995 sonic boom study, in which F-16XL #849 flew 200 feet behind a NASA SR-71 to probe the boundary of the SR-71’s supersonic shock wave. These tests measured and recorded the shape and intensity of the shock waves. Those studies helped NASA’s High-Speed Civil Transport (HSCT) program engineers to better understand supersonic shock waves in order to reduce sonic boom intensity near populated areas.

The two-seat F-16XL was extensively modified by NASA Dryden for the Supersonic Boundary Layer Control research project in the mid-1990s. A turbine-driven suction system was installed in the aircraft’s fuselage while a modified, thickened left-wing pulled in boundary layer air flowing over the wing to enable laminar, or smooth, airflow over the wing. The aircraft last flew in 1996 and is reportedly no longer airworthy.

The prototype was placed again in storage, this time at NASA Dryden; yet in 2007, NASA approached Lockheed Martin – which had acquired General Dynamics’ aviation business – to conduct further tests on the feasibility of returning one of the prototypes to flight status. That program finally ended in 2008, and both of the prototypes were officially retired and returned to storage yet again. Today, one of the two F-16XL prototypes now remains in storage at the Air Force Flight Center Museum at Edwards, while the other is on display at the Museum Air Park – a testament to what could have been for the Fighting Falcon.

On October 5, 1993, Langley’s F-16XL High Lift jet was rolled out with a dynamic yellow and black paint job for Aero-Dynamic Flow Studies in High Speed Research.

F-16XL. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Expert Biography: A Senior Editor for 1945, Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers, and websites with over 3,000 published pieces over a twenty-year career in journalism. He regularly writes about military hardware, firearms history, cybersecurity, and international affairs. Peter is also a Contributing Writer for Forbes. You can follow him on Twitter: @PeterSuciu.