There is never a good time for a political showdown that carries with it the possibility that the U.S. government might default, even briefly, on its debt obligations. However, now is an especially bad time for our politicians to play a game of chicken with the country’s credit.

The recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank suggest we are in the midst of a rolling regional bank crisis that could spread to the non-bank part of the financial sector. Meanwhile, the economy could be on the cusp of a recession. The Federal Reserve is slamming the monetary policy brakes to curb the highest inflation in decades even as regional banks tighten lending conditions to prop up their shaky balance sheets. The last thing we now need is a debt crisis that could complicate an already messy economic picture by raising questions both at home and abroad about the full faith and credit of the United States government.

In a letter to Congress, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen is now warning that the government could hit the debt ceiling as early as June. She warns of a catastrophe if the debt ceiling is breached and the government is forced to default on its debt obligations.

While no one knows exactly what would happen in the event of an unprecedented U.S. government default on its debt, Yellen’s warning of mayhem in financial markets is plausible. In 2011, when debt ceiling negotiations went down to the wire, the stock market tanked, borrowing costs went up, and Standard and Poor’s stripped the U.S. government of its coveted AAA bond rating. This all occurred even though a deal was struck at the last moment and the U.S. government avoided default. One shudders to think what would have happened in financial markets had the government actually defaulted.

Given how high the stakes are, it is lamentable that at this late hour a seemingly unbridgeable gap on this issue separates House Speaker Kevin McCarthy from President Joe Biden. McCarthy clings to his position that the Republican Party will not support a debt ceiling increase without a commitment to deep public-spending cuts. He does so even though he knows full well that making deep cuts to Biden’s spending agenda, including the president’s student loan program and additional funding for the IRS, is anathema to the Democratic Party.

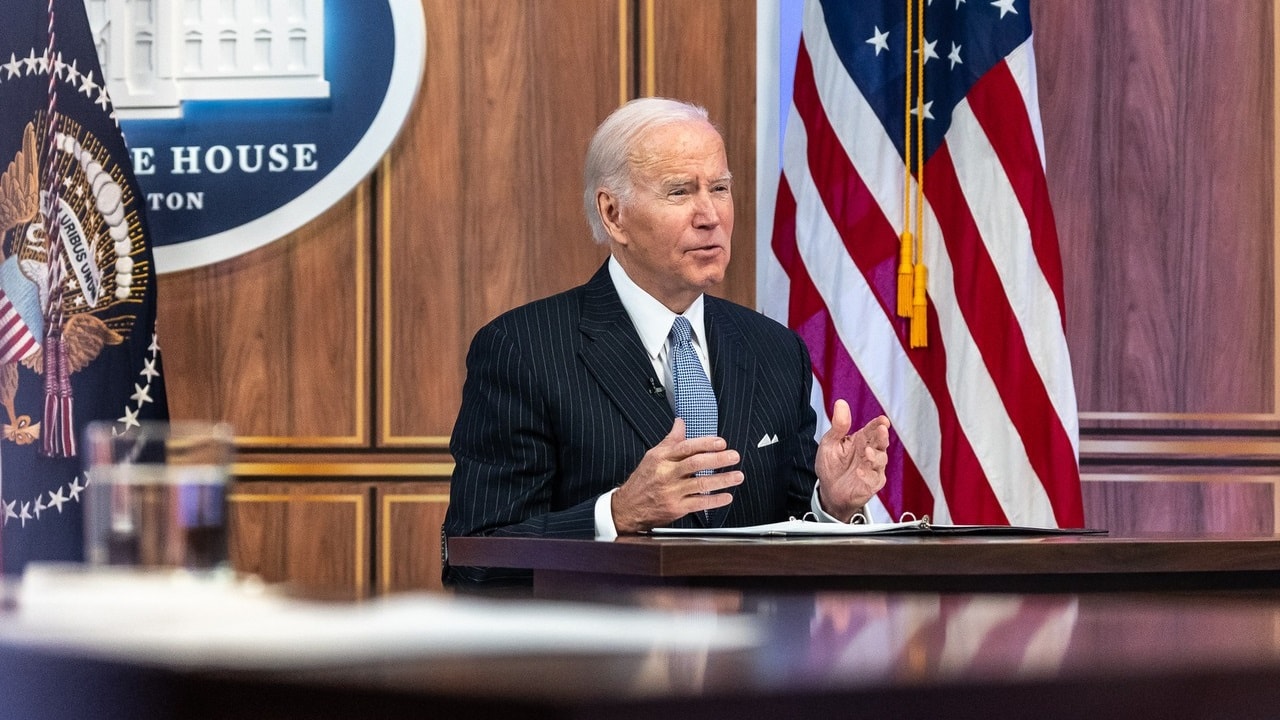

For his part, Biden insists that the ceiling should be raised with no strings attached to accommodate the spending increases that Congress already approved, as has been done on numerous previous occasions. At the same time, both sides are trying to pin the blame for any economic and financial-market disaster on the other side, hoping their opponent will blink as we all stare over the abyss.

In 2008, following the Lehman bankruptcy, then-President George Bush struggled to secure congressional approval for his Troubled Asset Relief Program. At least, he struggled until the stock market swooned and a potential financial disaster stared Congress right in the face. Congress eventually did the right thing and approved that program. We have to hope that similar turbulence will not be needed now to get McCarthy and Biden to budge from their hardline positions and reach a sensible compromise that will spare the country from financial market disaster.

If there is a glimmer of hope, it is that Biden has agreed to sit down with McCarthy next week to discuss the issue. We have to hope that when they meet, they will put politics aside and find common ground on the need to find the means to put our country’s finances on a sounder footing by curbing spending and by closing tax loopholes.

A sensible start might involve raising the debt ceiling for a few months to give time for substantive negotiations on an economic program that might be in the country’s long-term economic interest. Such a compromise might represent a start to ending Washington’s current political dysfunction and save the country from an economic and financial market calamity.

MORE: Kamala Harris Is a Disaster

MORE: Joe Biden – Headed For Impeachment?

Dr. Desmond Lachman is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.

Note: This piece has been updated to fix a coding issue. We apologize for any issues.