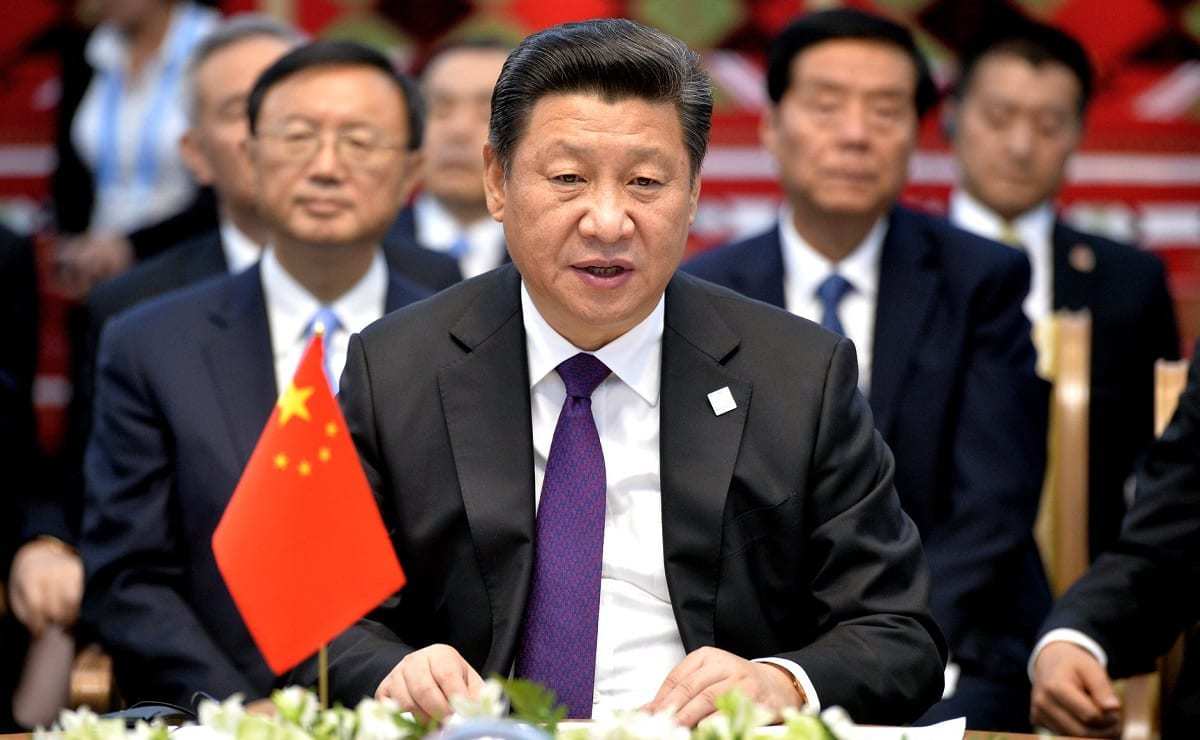

In his recent meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang, U.S. Ambassador Nicholas Burns reportedly emphasized the importance of stabilizing the bilateral relationship. After an alarming downturn in U.S.-China relations, an easing of tensions could indeed provide a welcome breather for two countries confronting intractable domestic problems. Washington continues to grapple with slowing growth, bitter partisan feuding, and surging gun violence, among other issues. China’s government faces its own formidable challenges, including weakening economic performance, grim demographic trends, and stubbornly high youth unemployment. Regarding China’s national-security threats, Xi Jinping said at the 20th Party Congress that authorities had at best contained the menaces of “ethnic separatism, religious extremists, and violent terrorists,” and merely made “important progress” against crime.

No One Has Seen a Rivalry Like This

With their weakened state capacity, disengaged publics, and imbalanced economies, the United States and China break the pattern seen in other rivalries between great powers. The recognition that U.S.-China competition differs dramatically from that of the Cold War is hardly novel. But less remarked-upon are the ways in which the current rivalry indeed differs from all great-power rivalries over the past two centuries.

The Cold War featured its own distinctive dynamics, but it shared important features with the two World Wars, and even with the wars of the Napoleonic era. The state of technologies differed dramatically, of course, but the similarities in social, political, and economic features are striking. Those epic contests involved centralized, unitary states with a high degree of internal cohesion and robust patriotic popular support. Governments enjoyed strong legitimacy, in part due to the expansion of opportunities for political participation and economic self-betterment. Industrial Age warfare typically centered on strategies of mass mobilization that permitted the fielding of vast armies consisting of citizen-soldiers equipped with standardized uniforms and equipment.

Noting the jarring contrast with such rivalries, baffled observers have struggled to make sense of the novel features of the current contest. Some have insisted that the two countries are headed for conflict. Others reject this view, arguing war is hardly inevitable and urging a more responsible approach to managing competition. Still others question the wisdom of competition at all and urge greater cooperation instead.

The Rise of Neomedievalism

A starting point for making sense of the U.S.-China rivalry’s unusual features is to recognize that our world is experiencing a moment of epochal transformation. In a recent RAND report, we present evidence that suggests the world entered a new epoch, which we call “neomedievalism,” beginning around 2000. This epoch is characterized by weakening states, fragmenting societies, imbalanced economies, pervasive threats, and the informalization of warfare. Such trends evoke patterns commonly seen in pre-industrial societies. They stem from the waning strength of the developed countries that created the Industrial Age in the first place. The net result is likely to be a severe weakening of all states, with profound implications for U.S. national security.

These trends will also impact our nation’s competition with China in at least three ways. First, weakening states will likely become a central feature of the contemporary contest. Nation-states are declining in political legitimacy and governance capacity. This weakness opens vulnerabilities and opportunities for competition, and it delivers contingencies that defense planners need to account for.

Second, coping with domestic and transnational threats may be just as important as deterring a conventional military attack. The principal threat to states increasingly stems from internal rather than external sources — sources such as pandemics, crime, and political violence. Because failure to ensure domestic security directly implicates the legitimacy of the state, controlling such dangers will become an urgent priority. Resources may need to be allocated accordingly.

Third, the transition from an industrial to a neomedieval era may carry more dangers than a potential power transition between China and the United States. The proliferation of hazards it will bring about will confront perpetually weak states and a scarcity of resources to address the issues. U.S.-China peacetime competition seems like it will unfold under conditions featuring a high degree of international disorder; diminishing state legitimacy and capacity; pervasive and acute domestic challenges; and severe constraints imposed by economic and social factors that are vastly different from what industrial nation-states experienced in the 19th and 20th centuries.

These trends will decrease the relevance of many of the strategies employed by great powers against one another over the past two centuries. New theories and ideas will be required to cope with problems largely unknown to the great-power rivals of the recent past. The United States has adapted in the past to overcome immense international challenges. It will need to do so again to succeed in an era of neomedievalism.

Dr. Timothy R. Heath is a senior international defense researcher at the RAND Corporation.