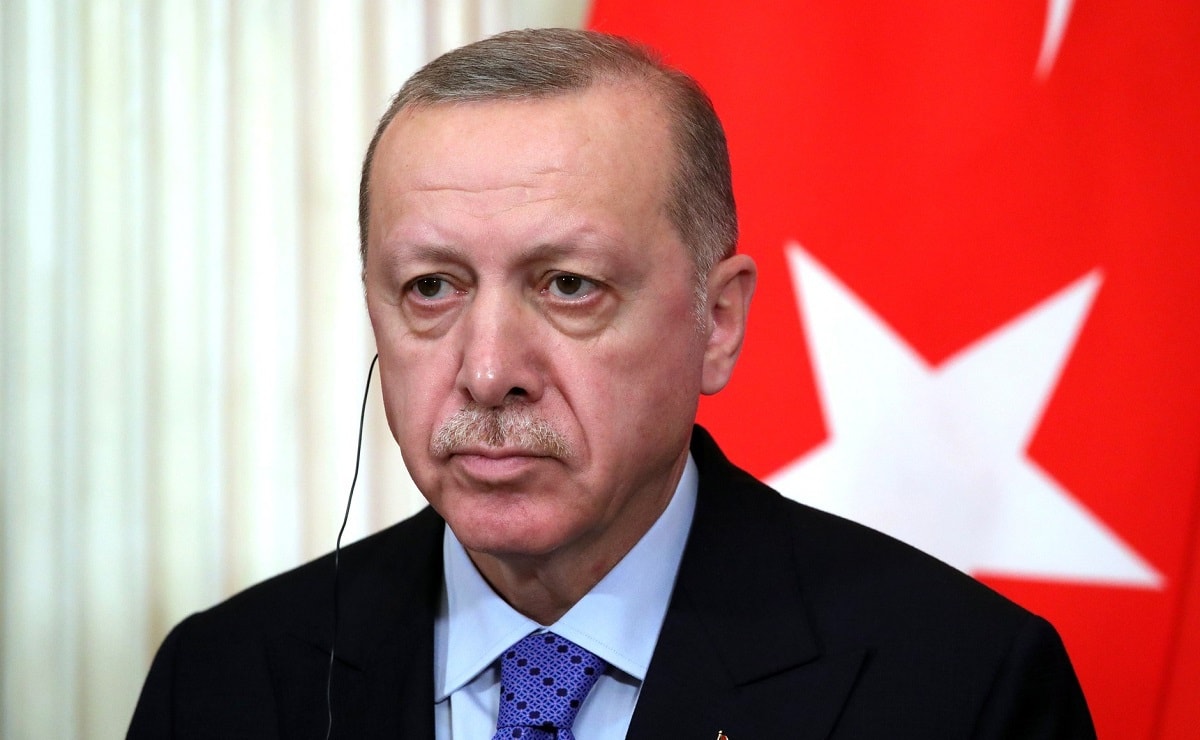

Turkish voters in May re-elected Recep Tayyip Erdogan for a third five-year term as president. In the weeks since, some analysts have started to wonder whether this is the moment that Erdogan will shift Turkish foreign policy to once again align with its traditional Western orientation.

Ever since the 2016 coup attempt that threatened to forcibly remove Erdogan from power, Turkey’s veteran leader has incrementally chipped away at the country’s credentials as a stalwart member of the Western alliance. This is because Erdogan accused the West of backing the coup. The history of Erdogan’s anti-Westernism goes back further, but it has been particularly visible during the process of NATO’s expansion to bring in Sweden and Finland. Turkey spent 12 months throwing up roadblocks to prevent the accession of the two Scandinavian countries. While it finally ratified Finland’s bid, Sweden is still in the doghouse. Many in NATO, as well as officials in the U.S. government, openly question Erdogan’s commitment to the West.

That said, some also thought Erdogan’s posturing was situational — that the bluster was related to his efforts to be re-elected, and therefore it would likely pass. This perspective is misguided.

Promising Signs, But We’ve Seen It Before

The argument goes something like this: In the run-up to elections, Erdogan needed to give voters a reason to choose him. The Turkish economy is plagued by high inflation and an eroded national currency. Those chronic issues joined with a devastating series of earthquakes at the beginning of 2023 to cast a long shadow over Erdogan’s appeal. Erdogan’s entire brand is predicated on strong economic growth. In its absence, he chose to go negative, and he used the foreign policy arena to secure public support.

A hawkish posture in the Eastern Mediterranean resulted in amped-up rhetoric about invading Greek islands and taking them back for Turkey. A threat to annex Northern Cyprus was further aggravated by his recalcitrant attitude toward NATO expansion. Worse, Ankara has refused to participate in international sanctions against Russia, with credible evidence to suggest that Ankara profits from the war in Ukraine.

At home, Erdogan has flouted the rule of law to the greatest possible extent. The country does not even implement the binding rulings of the European Court of Human Rights, which has directed the release of political prisoners such as philanthropist and human rights activist Osman Kavala, among countless others.

You may wonder what all this has to do with winning public support. It’s simple: The Turkish public largely admires Erdogan’s aggressive posture on the world stage. The more Erdogan barks at the West, threatens its neighbors, and pursues what he has referred to as an independent foreign policy, the prouder voters feel. It is a society-wide reflex born out of decades of ties with the West, which many Turks believe has undermined Turkey’s prestige and its rightful place as a powerful country. The blocking of Turkey’s accession to the European Union has led to the most visible expressions of society-wide resentment.

Now that Erdogan has won re-election, should we assume that Erdogan will abandon his aggressive use of foreign policy as a tool for nationalist posturing? I would not bet the house on it. On the positive side, Erdogan has abandoned his aggressive stance toward Greece. Gone are the threats to reclaim Greek islands, as well as the number of violations of Greek airspace in the Aegean. Instead, we have seen the reinstitution of bilateral trustbuilding measures between the Greek and Turkish governments, as well as a fresh round of diplomacy aimed at finding a negotiated settlement of the Cyprus question.

At the NATO summit in Vilnius, Erdogan indicated that Turkey would take up Sweden’s membership of NATO by referring it to the Turkish parliament for ratification when it comes back into session in October. Following a decade-plus of fractured relations with key Western partners, Erdogan has made some moves to rebuild his relationships with Israel, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. All of this suggests that Erdogan may have abandoned his toxic brand of foreign policy independence. Not many people in positions of authority are buying it, however — leaders are accustomed to Erdogan’s sharp U-turns.

A Duck-and-Weave Foreign Policy

The qualifying term to describe all the positive developments discussed above is “for now.” Erdogan has de-escalated tensions with Greece and Cyprus mainly because of the influence their lobbies have in Washington. Key lawmakers in Congress — such as Sen. Bob Menendez, who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations Committee — are sympathetic to the Hellenic position, which sees Erdogan as a threat. Menendez and the committee he chairs are preventing the sale of new F-16 fighter jets to Turkey. For this acquisition to go through, Turkey needs to satisfy congressional requirements and not threaten Cyprus and Greece.

Much the same can be said for his attempts to rebuild his image in Turkey’s region. Erdogan is likely to meet with Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, and he has already shaken hands with the Egyptian leader, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, whom he once referred to as a tyrant. This is in addition to conducting a tour of the UAE and Saudi Arabia following his re-election. Erdogan secured notable investments and trade deals as part of that effort.

Erdogan behaves this way for now, because if he does not mend ties with the powers cited, Ankara will be isolated. How far Erdogan’s shaking of hands with regional leaders will go to actually rebuilding substantive, close ties with the countries in question can be no more than a guess.

One thing is clear, however, and has been well explained by my colleague Steven Cook, who recently wrote that Erdogan’s goal is the “pursuit of three basic foreign-policy ideas: strategic independence, power, and prosperity.”

I would add that these three identifiers mean different things to Erdogan than to his counterparts. If Ankara does manage to acquire F-16’s from Washington, there is no guarantee it will not engage in antagonistic behavior toward its Hellenic neighbors. Within NATO, let’s assume the Turkish parliament ratifies Sweden membership. Can we be certain that at some point in the near future, Erdogan would not hold up NATO business, perhaps seeking to leverage another defense acquisition from Washington? If Ankara can procure investment streams from the Gulf, how sure can we be that Erdogan will continue rebuilding substantive political dialogue with Israel?

We should abandon the notion that Erdogan’s Turkey will anchor itself with the West. Leaders like Erdogan — and perhaps Viktor Orban of Hungary — have figured out that wholesale commitment to any cause or alliance pays low dividends. What pays more is leveraging one’s position inside entities such as NATO or the European Union. For now, it fits Erdogan to suit up as a team player. Turkey will hold its local and municipal elections in May 2024, and there is strong evidence to suggest that a strong economy will not be on offer as a winning message. Around the new year, I am waiting to see which country Erdogan will demonize, as he pivots back to emphasizing an “independent” foreign policy.

Sinan Ciddi is a non-resident senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), where he contributes to FDD’s Turkey Program and Center on Military and Political Power (CMPP).