The Lancet loitering munition is a standout success for Russia. While other weapons have performed below expectation during the invasion of Ukraine, this 35-pound kamikaze drone has proven capable of taking out a wide range of targets, including main battle tanks and parked aircraft, from far over the horizon. This performance should be enough to make Western analysts take note, but potentially more alarming is the Lancet’s impressive track record against artillery and air defenses.

New figures compiled by Russian sources suggest that Lancets are now shipping in larger volumes, and the threat will get much worse.

Rise of the Lancet

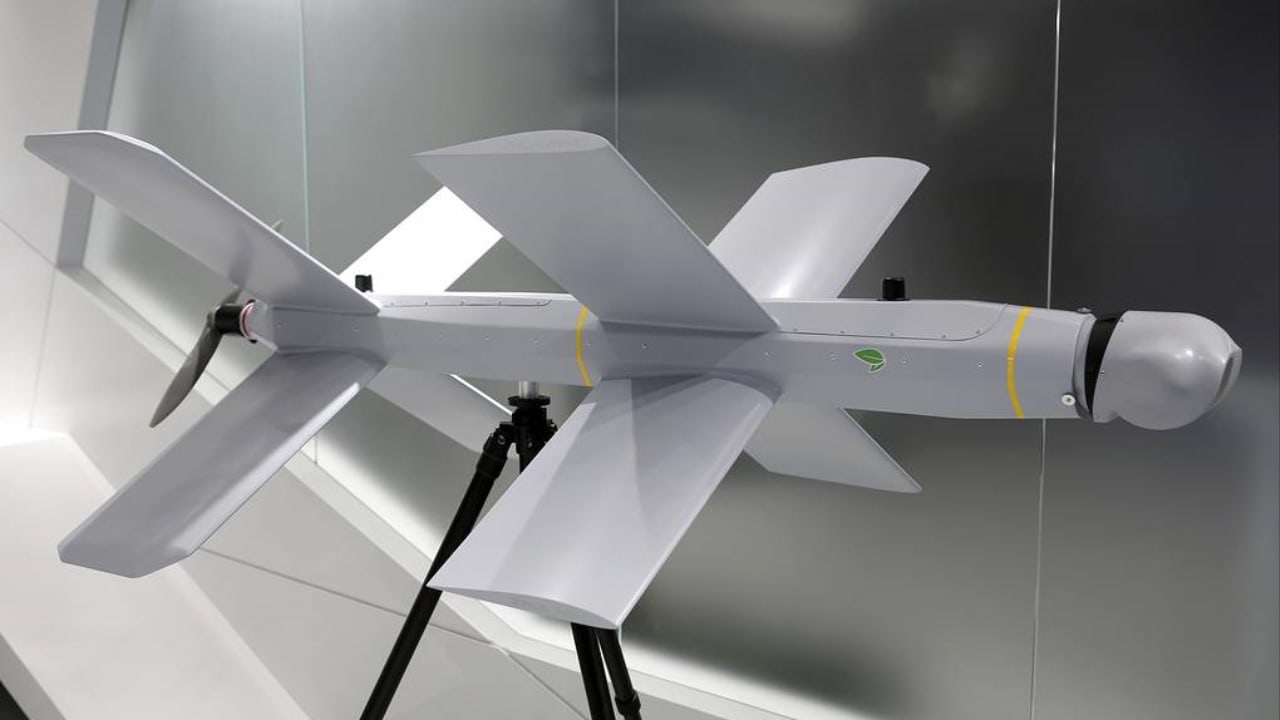

Unveiled in 2019, the Lancet is Russia’s first purpose-built loitering munition. The Lancet-3 is made by Zala Aero Group, a subsidiary of the Kalashnikov concern, and it comes in two varieties. The smaller Izdeliye-52 has two conspicuous X-shaped wings and carries a 6.5-pound warhead, while the Izdeliye-51 has an 11-pound warhead.

After being used on a trial basis in Syria in 2021, the Lancet was rushed into full-scale service for this conflict. The first known use in Ukraine was in July 2022, some five months into the invasion. Since then it has been used in small but growing numbers.

“It is used sparingly, most likely by the SOF [Special Operations Forces] and similar units,” Samuel Bendett, an analyst with the CNA, CNAS, and CSIS told 19FortyFive. “And their use is creating difficulties for the Ukrainian military.”

At first only a handful of Lancet strike videos were posted each month. But this January, 22 Lancet attack videos appeared. That number rose to 62 in May, and 124 in August. The makers claim they are mass-producing the weapon at a new facility, so what we are seeing now is only the start. This growth in production is taking place despite the fact that the Lancet uses Western-made electronics, which in theory should be impossible for Russia to obtain.

“There are signs that the Russian defense industry is ramping up Lancet production, along with improvements that lead to more advanced designs,” says Bendett.

The Lancet is launched from a catapult rail and transmits video back to the operator. Lancets are reportedly flown in conjunction with reconnaissance drones which spot targets and relay coordinates. The Lancet operator flies to the target area, visually confirms the target, and carries out the strike.

An electric propeller drives the Lancet at around 70 miles per hour. This slow speed makes it an easier target than a guided missile or other munition.

“Every day we shoot down at least one or two of these Lancets,” Yuriy Sak, an adviser to Ukraine’s defense minister, told Reuters. “But it’s not a 100 percent interception rate, unfortunately.”

Early Lancet attacks were all on static targets. More recent videos have shown hits on moving vehicles. This may indicate a change in doctrine or an improvement in operator skill levels.

However, even now Lancets frequently miss. Videos posted online usually show successful attacks, but in the case of Lancets, optimistic posters sometimes put up videos that on close inspection turn out to be near-misses.

Russian open source analysts Lost Armor have compiled and classified every known Lancet strike video online. About 7% of Lancet attack videos clearly show misses, and in another 8% it is impossible to tell if the target is actually hit. A small number of videos, perhaps 1% of the total, show Lancets hitting what are identifiable as inflatable or wooden dummies.

The rest are doing real damage.

Target Set

One Ukrainian analyst puts the success rate of the Lancet at approximately 25%-30%, suggesting that there are a couple of misses or shootdowns for each of the strike videos seen.

According to Lost Armor, as of Oct. 3 there are 667 Lancet strike videos. Of these, 210 are classed as target destroyed (31%), 355 target damaged (53%), 48 miss (7%), and 52 are unknown (7%) . In particular, the heavy armor of tanks sometimes shrugs off the Lancet’s relatively small warhead.

This suggests that around 2,000 Lancets have destroyed 200 targets and damaged hundreds. That may seem low, but with each Lancet costing perhaps $35,000 and each target costing millions, the Lancet is extremely cost-effective.

Twenty-five percent of the targets comprised tanks and lighter armored vehicles — in at least one case, a German-supplied Leopard-2 tank. Analysts suggest that the Leopard was already immobilized by a mine or missile before being finished off by the Lancet. As in the other videos, the tank is observed by a Russian drone before, during, and after the strike. Whether or not the Lancet was the sole cause of destruction, this episode suggests that even the latest and best -protected armor is vulnerable to Lancet strikes from long range. If you accept a value of $11 million for a Leopard-2, that’s about 300 Lancets.

Ten percent of the targets were motor vehicles and other relatively low-value targets. These may have been selected when a Lancet failed to find its intended target (or this had already been destroyed), or where a vehicle carrying ammunition was considered a priority. Cheap FPV drones costing a few hundred dollars apiece are far better suited to the task of hitting enemy transport or troops in trenches.

Another 15% of the targets were very high value: Ukrainian surface-to-air missile launchers and radar systems. These are typically kept several miles back from the front line, but not far enough to be out of Lancet range. Knocking these out allows Russia to use its air superiority in helicopters and strike aircraft on the battlefield.

The Artillery Killer

By far the largest number of Lancet strike videos show attacks on Ukrainian artillery, both towed and self-propelled guns. As a recent report from UK defense think tank RUSI notes, Russian forces now use the Lancet extensively as a counter-battery weapon. Artillery is the traditional means of striking enemy artillery, but the long range of the Lancet, and its ability to seek out hidden targets on the ground, give it real advantages. Additionally, the Lancet operator remains hidden and will not be targeted by counter-battery fire.

Lost Armor counts 142 hits on self-propelled artillery and 170 on guns and mortars. These are significant numbers. According to the database compiled by open-source analysts Oryx, Ukraine has suffered 222 self-propelled guns destroyed or damaged. This suggests that Lancets may be responsible for 64% of Ukrainian self-propelled gun losses.

The proportion for towed artillery appears unbelievably high: 169 hits, compared to the 160 destroyed or damaged and recorded by Oryx. Towed artillery is much harder to destroy than a self-propelled gun, even when hit. The latter is a tracked vehicle with a store of flammable fuel and explosive ammunition on board, either of which can be set off by a Lancet strike. A towed artillery piece, by contrast, is a more solid piece of machinery able to survive the blast and minor shrapnel fragments of a Lancet hit.

“The lethality of Lancet is often insufficient,” according to the RUSI report. “One officer also said that although he had seen his gun ‘destroyed’ several times online, it remained alive and well.”

This tallies with previous conflicts in which towed artillery has proven more robust to counter-battery fire. Crews may be injured or killed, but the guns themselves tend to survive and remain serviceable. In WWII, the loss rate for self-propelled guns was two to three times higher than for towed artillery. So many of the Lancet hits on towed artillery likely did not result in kills.

The claim in May by Russia’s RIA Novosti that Lancet-3s had destroyed 45% of Ukraine’s Western-supplied artillery is likely a wild exaggeration based on this sort of overcounting. But it is clear that a high proportion of Ukrainian artillery losses are from Lancets, and those losses are likely to increase as more Lancets are deployed.

Hard Lessons Ahead

The situation in Ukraine is evolving fast, and the effectiveness of Lancets and other loitering munitions may yet be blunted. Ukrainian artillery crews use protective nets that have some success in stopping Lancets. Jammers are now issued widely, but it is not clear how effective they are. The Lancets, and the defensive measures used to stop them, will both probably improve.

So far, the Lancet’s main limitation seems to be limited numbers.

“There are still not enough of them to saturate the front,” says Bendett, noting commentary in Russian military Telegram about the demand for more such drones.

Another concern is that the Lancet’s range is being stretched. In September, a Russian Lancet destroyed a parked Ukrainian MiG-29 jet at a range of at least 50 miles. According to Russian media, this was achieved with the aid of unspecified design modifications.

The success of the Lancet has also inspired a number of Russian companies and volunteer groups to produce low-cost Lancet look-alikes. These offer similar capabilities for a fraction of the cost. According to makers, they could be fielded by the thousands.

These rivals include the Skalpel made by the Vostok design bureau, and the Oko company’s Privet-82. Both companies say they can mass-produce as soon as they get an order. Volunteer group Archangel has also produced a prototype fixed-wing loitering munition that they say is much cheaper than the Lancet. Bendett notes that competitors tend to have shorter range — around 25 miles or less. Though less sophisticated, they may still be dangerous.

Zala clearly aims to produce a lot more loitering munitions, and the company has already shown video of a Lancet swarm in which one operator controls several Lancets in a simultaneous strike. This would increase the chances that at least one gets through.

Bendett notes that Zala has a well established relationship with the Russian government and military, so others may struggle to break into the market. But with increased Lancet production and several other possible contenders also pushing loitering munitions, we are likely to see far more strikes from this type of weapon in the coming year.

For its part, Ukraine has used large numbers of small FPV kamikazes to great effect. But we have yet to see anything on their side with the size and range of the Lancet. This is likely to change in the very near future. The shadowy U.S.-supplied Phoenix Ghost, of which there are no known images, may be the nearest current equivalent.

Loitering munitions do not make tanks or artillery obsolete. But they may push casualties higher and drive new types of thinking and new styles of warfare. There are hard lessons to be learned, for Ukraine and the rest of the world.

About the Author

David Hambling is a London-based journalist, author and consultant specializing in defense technology with over 20 years’ experience. He writes for Aviation Week, Forbes, The Economist, New Scientist, Popular Mechanics, WIRED and others. His books include “Weapons Grade: How Modern Warfare Gave Birth to Our High-tech World” (2005) and “Swarm Troopers: How small drones will conquer the world” (2015). He has been closely watching the continued evolution of small military drones. Follow him @David_Hambling