The recent bilateral meetings between U.S. and Chinese diplomats stumbled into acrimonious territory as the two powers accused each other of upsetting international norms.

The United States accused the Chinese government of human rights abuses in Hong Kong and Xinjiang with the Chinese retaliating by pointing out the conditions that gave rise to the Black Lives Matter movement as evidence of U.S. hypocrisy on these issues. The U.S. point alleging that domestic policies enacted by Beijing affect the greater world was met by the Chinese counterexample from diplomat Yang Jiechi of, “We do not believe in invading through the use of force, or to topple other regimes through various means, or to massacre the people of other countries because all of those would only cause turmoil and instability in this world.”

Whatever one thinks of either Washington or Beijing’s domestic policies, signs around the world point to the U.S. insistence on speaking of its own ideology as the universal values of the international system as becoming a product of a bygone era.

The Chinese have already shown that two can play the game of making human rights reports about their geopolitical rivals. Both the U.S. and China have taken recent hits at their international reputation due to coronavirus response-related issues. The U.S. in particular has seen oscillating levels of international approval with some truly dramatic dips ever since the Iraq War of 2003, implying that the Chinese critique of U.S. interventionism holds sway with many around the world.

The obvious double standards applied to U.S. allies like Saudi Arabia compared to rivals like Russia and China increasingly make claims to moral leadership ring hollow in the ears of many. This unnecessary double standard causes Washington’s leadership to become less popular.

This is not the time to be pushing a framework of a “New Cold War” or to justify alliance networks based off of supposedly creeping “Authoritarianism”. What we are seeing, instead, is a more multi-polar world arising. One in which smaller countries have more freedom to bargain for better deals between different major powers regardless of their domestic politics.

Ideology will take a backseat to calculations of interest and security, and so forcing such a conception onto U.S. foreign policy will hobble the interests of Washington’s diplomats compared to countries like Beijing which so far have no such hang-ups. This gives China an advantage at reaching compromises with other countries in negotiations.

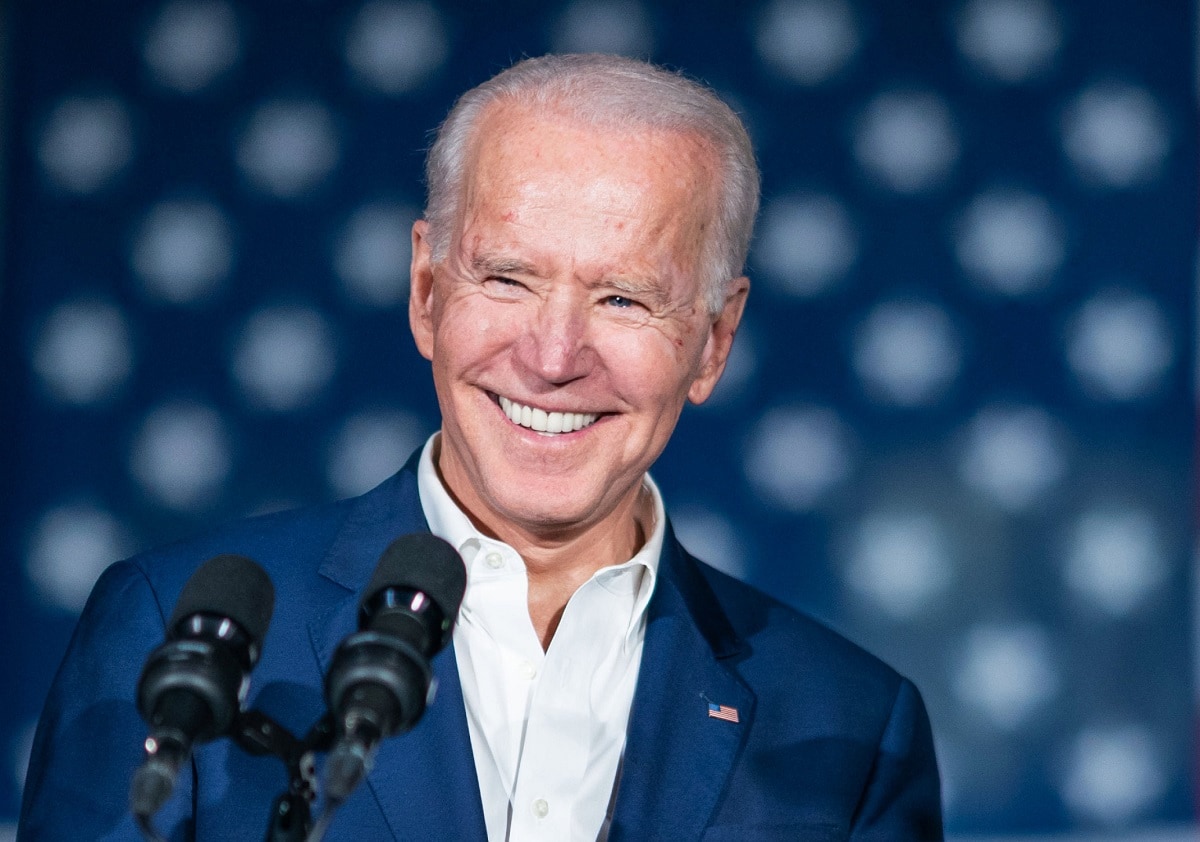

The Biden Administration seems to be genuinely taken aback by the pushback they get from rivals and ostensible allies alike, as the talks with Turkey at the most recent NATO summit show, it seems that many U.S. diplomats are operating under an assumption that merely stating “America is back” reboots the pre-2016 world order.

What the U.S. should instead do, however, is pursue a strategy founded on sound practical conceptions of its grand strategy that delivers benefits to the American people without the costs of attempting to wage a global ideological battle that restricts diplomatic options around the world. An attempt to resurrect the bipolar rivalry as existed after the Second World War and until the collapse of the Soviet Union would be a reckless mistake.

The United States has an immensely favorable combination of geographic position, military power, economic influence, and potential appeal in the realm of diplomacy. If it so chose, it could be seen as a protector of smaller countries’ sovereignty and key balancer in world affairs rather than a belligerent aggressor intent on social engineering. But this kind of welcome realignment to a sustainable policy based around national interests defined by a favorable cost/benefit calculation for the American people is undermined by attachments to obsolete ideologies about stated U.S. civic values being the glue holding the international system together.

What could actually bring about more stability is an honest acknowledgment of everyone’s interests and seeking constructive compromises through a diplomatic realism that requires no litmus tests for countries with different internal politics. Approaching great power competition in an ideological manner is a recipe for needless escalation.

The Biden Administration would be wise to take notice of the existing world they operate in, not the one they seem to believe they can recreate.

Christopher Mott is an international relations specialist and author of The Formless Empire: A Short History of Diplomacy and Warfare in Central Asia.