Last October, Cyber Command tweeted a picture of a Russian bear dropping a Halloween candy bucket full of its latest malware trick or treats. From conception to deployment, the effort took 22 days.

The American military may be the finest in the world but its social media skills are embarrassing. (In true government form, the number of days spent producing the image was one less than the number of pages in the report detailing the exercise.)

If America is to succeed in the contested information space, then it should leave the mission to the nation’s civilian agencies.

The History

Once upon a time, the United States was extremely capable of information operations and influence campaigns.

During the Cold War, the United States applied an array of diplomatic and intelligence resources to counter Soviet information activities. Through coordinated campaigns in print, on radio, libraries abroad, and a roster of speakers, the U.S. successfully introduced foreign audiences to American interests and values. When necessary, American also covertly funded friendly parties and unions in other countries and created front organizations to expose communist atrocities. When given a choice between their regime’s state media and Radio Free Europe, oppressed Eastern Europeans chose the latter.

When the Cold War ended, the United States simply dismantled these instruments — peace meant America no longer needed these wartime tools.

However, American adversaries do not recognize the difference between peace and war and they have employed information energetically since their founding.

In the 1920s, Lenin erected an elaborate but fictitious counter-revolutionary organization, the Trust, to lure and mark dissidents at home and abroad for elimination. The multi-year effort effectively decimated the anti-communist emigre movement. In the same decade, Mao recast the Long March, a disastrous military retreat, as an irresistible message to oppressed peasantry — “the road of the Red Army is their only road to liberation.” After prevailing in the civil war, the Party tasked its propaganda arm, the United Front Work Department, with disseminating communist orthodoxy and marginalizing dissent.

After Putin solidified his control of post-Soviet Russia, he rapidly revived the state’s information capabilities and redeployed it effectively — first against the country’s near abroad and then the West.

Under Xi, China’s United Front supports the regime’s efforts to foster the loyalty of overseas communities, infiltrate dissident groups, and burnish its image around the world.

In the process, they have de-panted the United States in the media narrative locker room.

In the Ukraine, Russian operatives prepped the battlefield by provoking native Russians and publishing sensationalist stories of imaginary atrocities. Then it inserted the now-infamous “little green men” that Russia shrewdly use to deflect responsibility for the unrest. America found it incredibly difficult to denounce an invasion that was or was not occurring. The Ukraine requested armor but the United States instead posted a hashtag and sent meals-ready-to-eat.

More ambitiously, Russia intruded in the 2016 American presidential election and upended the country’s political discourse for the next two years.

Amid the global pandemic, Chinese authorities effectively undermined theories that COVID emerged from one of its laboratories while threateningly reminding other countries of their dependence on their assistance — “if someone claims that China’s exports are toxic, then stop wearing China-made masks and protective gowns.”

More comprehensively, the Chinese leadership contrasted its authoritarian regime’s success in neutralizing the virus with the continuing struggles faced by the West’s democracies.

What To Do Now

A democratic republic, the United States cannot imitate the tactics of these authoritarian regimes.

It, however, can imitate key aspects of their approaches.

In both Russia and China, these entities reported directly to the national leadership, in part because the regimes are authoritarian, but also because their leadership recognizes information is fundamental to grand strategy.

In the Soviet Union, the entity responsible for information operations, Service A, was continuously elevated within the KGB, amply resourced with funding and manpower, and allied capabilities were subordinated into its operations. (Of equal importance, the operatives were unconventional thinkers and creative contrarians; one fearsome practitioner became a painter in retirement.) Under Putin, information campaigns have attained even greater prominence, permeating all aspects of Russian military and intelligence operations.

Similarly, China’s United Front serves as the coordinating body for multiple departments, each well-resourced in their own right, moving aggressively on multiple fronts. Efforts include sponsoring visits by prominent political, military, economic, and cultural figures; funding academic institutes and exchanges; and, providing Chinese language and cultural education. However, the initiatives provide a cover for covert aims — tracking citizens abroad, collecting intelligence, co-opting media organizations, creating pressure groups, isolating Taiwan, and quashing reports of genocide in Xinjiang. The Chinese Communist Party deems the United Front a critical tool in its twin objectives — ensuring the party’s supremacy and establishing the nation’s pre-eminence around the world.

In glaring contrast, the United States does not have a single unified definition of information or a strategy outlining its application as an instrument in service of the national interest.

Moreover, American information responsibilities and capabilities are fragmented across multiple entities. State is responsible for “strategic communications”; the CIA for analyzing foreign cyber threats; and Homeland Security for domestic cyber-security and protecting critical infrastructure.

Naturally, the Department of Defense is expected to contribute significantly and has devised a holistic definition.

According to joint doctrine, the information environment “is comprised of and aggregates numerous social, cultural, cognitive, technical, and physical attributes that act upon and impact knowledge, understanding, beliefs, world views, and, ultimately, actions of an individual, group, system, community, or organization.” Ultimately, “the information environment directly affects and transcends all operational environments.”

Clearly comprehensive but ultimately unwieldy.

The definition “includes technical systems and their use of data” as an aside, but of course, it is here where the American military excels — disrupting and destroying the enemy’s information technology assets and capabilities.

American armed forces turned off the power in downtown Belgrade, emasculated Iraqi command and control systems in back to back wars, and (allegedly) crippled Iranian nuclear centrifuges with malicious code. (Allegedly.)

However, even DOD has not yet consolidated the mission in a single entity.

The Under Secretary for Policy has been designated as the Principal Information Operations Advisor. Biden’s just-confirmed pick for the position, however, has had minimal experience with information operations. In fact, his only experience briefly jeopardized his nomination — his overly partisan tweets prompted concerns as to whether he could work with both parties in Congress.

The NSA celebrates its sixtieth anniversary next year and has been indispensable to American efforts to protecting sensitive communications while collecting information and data globally. The agency’s zeal in performing the latter mission backfired, however, when it was revealed allied communications were also being collected.

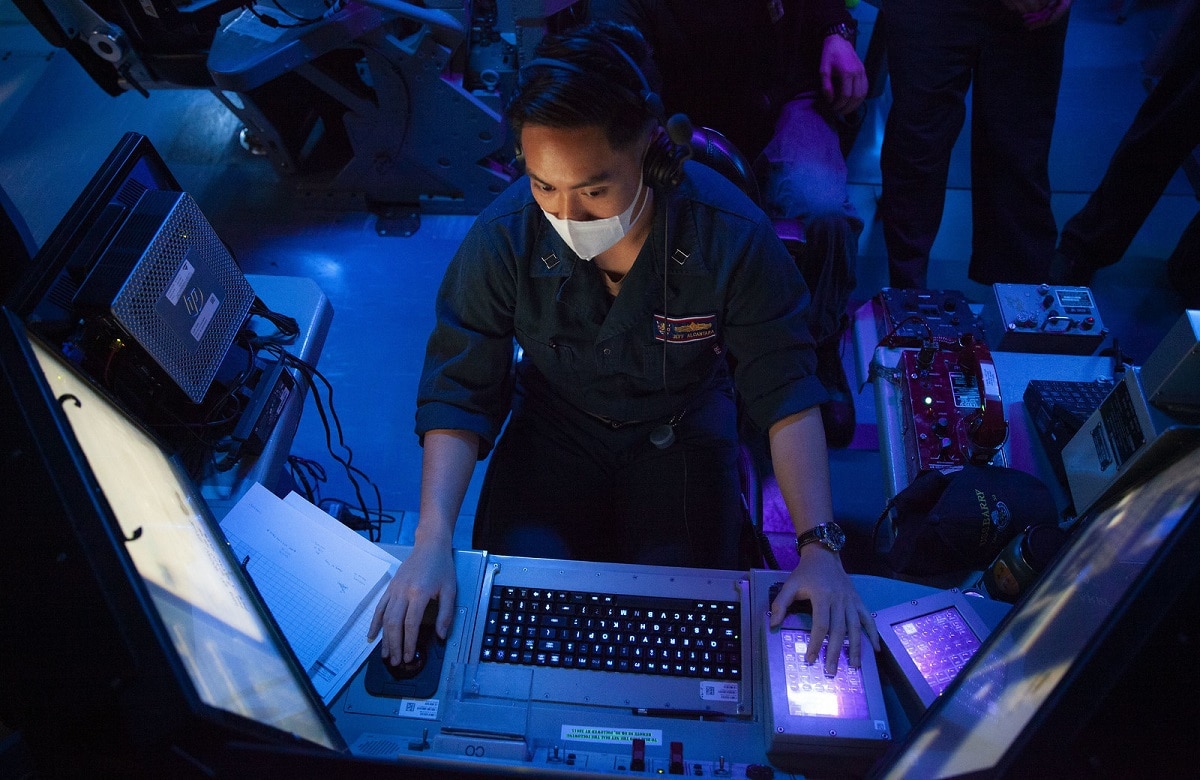

Within DOD, Cyber Command is responsible for offensive cyberspace operations and Special Operations Command is the lead for information operations. Unfortunately, at a March hearing, DOD witnesses acknowledged the military isn’t keeping up with information-warfare threats from Russia and China and reiterated the need for a whole-of-government approach.

One could fairly interpret the latter comment as a plea to be excused from the mission. During the global war on terrorism, the whole-of-government mantra was repeatedly endlessly and still the other departments barely showed up.

ISIS information operatives once tormented America with its relentless messaging. They’re also now dead because American bombs were more effective than tweets. DOD could be forgiven for wanting to be given a pass and to focus on kinetic operations.

Kennan, the architect of containment, recognized America’s belief that peace and war were distinct and would hinder its efforts to counter the Soviets. To succeed, Kennan’s solution was simple — wage “political warfare”. Most importantly, Kennan recommended the implementing entity would be staffed and led by civilians reporting directly to the President via the Secretary of State.

The United States would be wise to revisit this recommendation.

In Greek mythology, Athena is the goddess of just war but it is Hermes who is the herald of the gods.

To paraphrase the Scriptures, render unto Athena that which is Athena’s, render unto Hermes the things which are Hermes.

Jordan Prescott is a private contractor working in defense and national security since 2002. He has been published in RealClearDefense, The National Interest, Small Wars Journal, and Modern War Institute.