An old book from the 1950s explains How to Lie with Statistics. Author Darrell Huff alerts readers to be on guard against those who misuse numbers—wittingly or unwittingly—as an implement of persuasion. A world of mischief lurks within statistical analysis. Numbers are neutral. How people use them may be subjective.

And often is.

It turns out the same goes for visual imagery. Even seemingly objective imagery such as cartography can convey political messages as well as facts. So mapmaking, like mathematics, can mislead. In fact, it almost has to. It’s impossible to render a globe on a flat page with perfect fidelity. Some degree of distortion is baked into maps.

Think back to the caterwauling in 2012, when the Obama administration announced that the Pentagon would “pivot” to Asia, reapportioning naval and air forces in particular to favor the Pacific theater. Almost instantly Europhiles took to protesting that the pivot was a grave mistake because it meant that America was turning its back on Europe.

Uh, no. The standard U.S.-centric Mercator map of the world does convey that impression. But it’s a false impression. That’s because it splits the Eurasian supercontinent between the map’s leftward and rightward margins. It appears Washington must either face Europe across the Atlantic Ocean or do a one-eighty and face Asia across the North American continent and the Pacific. But glance at a Mercator map not centered on North America, and it becomes obvious how wrongheaded such complaints were. Better yet, look down from the North Pole and behold how sea traffic sweeps around both sides of Eurasia to reach the Pacific and Indian oceans.

Yes, it is possible to look westward from Washington DC to Tokyo, Taipei, or Beijing. It’s also possible to look eastward to Asia, South Asia in particular. And indeed expeditionary forces routinely make their way to the Indian Ocean—and sometimes beyond—from East Coast seaports such as Norfolk or Mayport. How do they get there? Across the Atlantic, through Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea, and thence through the Suez Canal (when it’s not plugged by a stranded container ship), the Red Sea, and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, the entryway to the western Indian Ocean. In other words, much Asia-bound shipping traverses Europe’s environs.

So even if Americans did reallocate policy energy and material resources to the Pacific, the pivot did not necessarily mean they were turning their backs on Europe. At worst it meant deflecting their attention a few degrees to the south and concentrating on waterways rather than European dry earth. Such is the power of maps to deform perceptions of the world and what human beings ought to do in it.

None of this would come as news to Fletcher School emeritus professor Alan K. Henrikson, who pioneered the concept of “mental maps” or “cognitive maps” back in the 1970s. For Henrikson a mental map is “an ordered but continually adapting structure of the mind” whereby “a person acquires, codes, stores, recalls, reorganizes, and applies, in thought or action, information about his or her large-scale geographic environment.” A mental map goes into action when someone has to make a “spatial decision,” namely a decision between alternative movements in geographic space.

A mental map, says Henrikson, is an “idea” about the world as much as an objective portrayal of physical space. And ideas are malleable. Time and speed mold mental maps. For instance, my conception of southern New England is distorted. It takes about an hour to make my way to the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, about twenty-three miles away. It also takes about an hour to journey to the seaside town of Mystic, Connecticut, which lies about fifty-seven miles away. Why? Simple. The route to Newport winds entirely through small-town Rhode Island, where speed limits are low and stoplights commonplace. The route to Mystic takes you along limited-access highways where the speed limit never drops below fifty mph and is often much higher. You flit to Mystic, plod to Newport.

Objectively speaking, it’s absurd to say Newport and Mystic are equidistant from the homestead; subjectively speaking, they are. Mental maps, in other words, need not be and oftentimes are not congruent with objective reality.

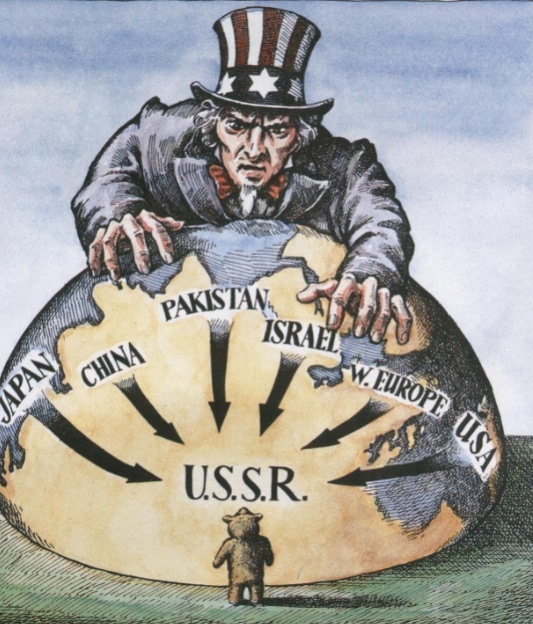

Henrikson hits on why mental maps fascinate, and why they’re integral to human affairs. Take this intriguing political map from the early Cold War, which purports to illustrate the Soviet worldview as the U.S. threat took shape in the late 1940s. (Its provenance is uncertain, but it must depict Moscow’s mental map sometime before 1949. It shows China as an American ally, which was true only until Mao Zedong and his Red Army triumphed in the Chinese Civil War that year.) First look at the scale of the contenders! Uncle Sam is a colossus coming over the horizon. He’s glowering at a tiny Russian teddy bear in the Eurasian heartland. Uncle Sam clutches at the Soviet Union. America exudes menace in this rendering.

The map also puts an ominous spin on U.S. strategy for the Cold War. By the late 1940s, U.S. political and military chieftains had more or less subscribed to the “containment” doctrine sketched by diplomat George F. Kennan in his famous Long Telegram and the abbreviated version published anonymously in Foreign Affairs. In brief, Kennan prophesied that if free nations could contain Soviet geographic expansion, they could siphon off the ideological fervor that fueled communism. Do that for long enough and the Soviet Union would mellow into something the free world could live with. Or Soviet communism would fall.

Kennan prescribed a strategy founded mainly on political and economic support, in hopes that Washington could help friendly nations facing communist subversion help themselves. By the late 1940s, nevertheless, Washington was busily constructing military alliances ringing the Soviet bloc, from NATO in Western Europe to SEATO in Southeast Asia to the U.S.-Japan alliance in Northeast Asia. The map depicts U.S. allies around the Eurasian perimeter, conveying a sense of encirclement. This is a reasonable interpretation of containment.

Intriguingly, though, the map also shows arrows thrusting inward from U.S. allies toward the Soviet heartland, as well as from North America across the Atlantic. Now, Americans did flirt with the notion of rolling back communism from time to time during the decades of cold war, but rollback never became official policy. Containment did take on a more martial tinge than Kennan wanted, but it remained almost entirely defensive in outlook. For example, the North Atlantic Treaty, NATO’s founding charter, contemplates military action only if a foe first launches an armed attack against a NATO ally. Strategic offense plays no part in the North Atlantic Treaty or any other accord constituting a U.S.-led alliance.

If this political map accurately conveys the Soviet worldview at the outset of the Cold War, worst-case thinking—if not paranoia—gripped Moscow. The United States had its Red Scare, the Soviet Union its American Scare.

Professor Henrikson’s mental-map concept, then, retains its power as an aid to knowing oneself and others forty-five years after he wrote it. During World War II, Franklin Roosevelt asked Americans to open their atlases and think about strategic geography. Yes. Look at your map—and look at it with a critical eye.

James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College. The views voiced here are his alone.