When the “Guns of August” began to fire in the summer of 1914, Europe was thrust into the worst war it had experienced to that point. Over the next four years, new weapons were introduced including the tank, while the airplane saw its first widespread use in combat.

However, one weapon truly changed modern warfare like no other – the machine gun.

Despite a misconception that military planners didn’t see the potential of the weapon, and expected to fight a 19th-century war – the truth is that most armies knew of the devastating power the weapons offered. They just didn’t expect the other side to fully understand it as well.

As a result, the machine gun changed the battlefield, and after Germany’s attempt to capture Paris and quickly end the war failed, the conflict transitioned to the now-familiar trenches where progress was measured in feet and yards instead of miles. It was the machine gun that made crossing “no man’s land” so very challenging.

Germany: Maschinengewehr 08

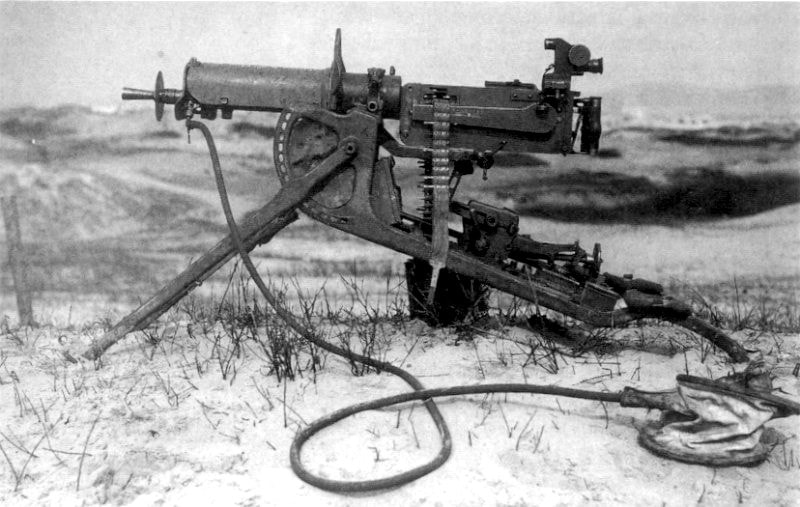

The German Army’s standard machine gun from the First World War – Maschinengewehr 08 – was essentially an adaptation of the already proven Maxim Machine Gun, which was designed in 1884 by Hiram S. Maxim. The American-born British inventor was reportedly told if he wanted to get rich “invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut 5 Deadliest Machinea5 Deadliest Machich others’ throats with greater facility.” Instead of a blade it was the machine gun.

As with most nations at the time Germany’s military planners didn’t foresee the weapon’s full potential, yet in 1914 there were 4,411 available to battlefield units. Not expecting a lengthy conflict, only some 200 MG08s were produced each month when the war broke out, but by 1917 that number was up to 14,400 per month! What Germany lacked in foresight it made up for quickly.

The water-cooled machine gun had a practical range of 2,000 meters and an extreme range of 3,600. With a rate of fire of 450-500 rounds per minute it could literally spray death across an open field – and was one of the factors that resulted in the armies digging in and settling into trench warfare.

France: Hotchkiss M1909 Benét–Mercié Machine Gun

The French were one of the few European powers not sold on the Maxim-style gun. A number of political issues were at play, and French nationalism was a big part of it. Instead a going with the flow, the French military adopted a different line of machine guns developed by the Hotchkiss et Cie company. Like Maxim, the Hotchkiss firm was founded by an American – in this case gunsmith Benjamin B. Hotchkiss.

In a strange twist of fate, the firm bought the rights to a machine gun design from Austrian nobleman Adolf Odkolek von Újezd – and thus was born the Hotchkiss M1909 Benét–Mercié Machine Gun.

The gas-operated weapon had a rate of fire of 400-600 rounds per minute, and was originally fed by a 30-round feed strip – later models were belt fed. Fearing that the factory might be overrun, production was moved to Lyon, while the British government invited the company to set up shop in Coventry. It was there that that a British model was produced for use with the early tanks, while a portable version – the Hotchkiss Portative – was used in the Palestine Campaign by various British units, most notably the Imperial Camel Corps.

Great Britain: Vickers Machine Gun

The British Army had been among the earliest adopters of the Maxim Gun, and during the First World War employed the Vickers Machine Gun, which improved upon the original design of the Maxim. The Vickers firm had bought out Maxim in 1896, and immediately went to work refining the weapon. The Vickers, which inverted the main firing mechanism and reduced its weight, served as the standard British machine gun throughout World War I and it remained in use in parts of the world until the 1970s.

While it could fire 450-500 rounds per minute and had an effective range of 2,000 meters it was anything but portable. Again, like the German Maxim it took several men to move it and that is why water-cooled guns like these were primarily used in a defensive role throughout the war.

Russian: Maxim M1910 Machine Gun

Another allied power simply went with what worked but improved it in its own notable ways. In 1910 the Imperial Russian Army adopted the Maxim gun, chambered in 7.62x54mmR. Whereas the Germans and British utilized tripods or sled, the Russians developed a wheel mount with gun shield. The early versions of the M1910 also featured a radiator cap on the top of the water jacket so that ice or even a snowball could be placed inside.

The short-recoil design allowed for a 600 round per minute rate of fire, and while the Sokolov mount in essence doubled the weight of the gun it also made transport much easier, even over rough ground. The machine gun went on to see use in the Russian Civil War, World War II and was even employed by the Red Chinese during the Korean War, while there are accounts of a few being used by the Vietcong.

United States: Browning M1917

When the United States entered the war in 1917 it was woefully unprepared, as in the years leading up to the conflict military planners showed little interest in a machine gun. In fact, the aging Colt Browning M1895 was still in use.

However, American ingenuity was ready if the military wasn’t. Prolific gun designer John Browning, who had designed the M1895, quickly refined the Maxim style design and that resulted in the M1917 Browning machine gun. The recoil-operated firearm had a rate of fire of 450 rounds per minute, which was improved upon to 600 rounds per minute with the M1917A1 version.

Browning even improved his design again with the M1919 air-cooled machine gun – a weapon still in use to this day. Had World War I continued there is little doubt these M1919 would have been at the front lines with the American Doughboys. Instead, it would serve throughout the world in the next World War and well beyond.

Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers and websites. He regularly writes about military small arms, and is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress, which is available on Amazon.com.