Defense Secretary Austin was in Singapore this week to give a speech on bolstering naval and other cooperation with partners in Southeast Asia. Discussions with foreign leaders in both the Philippines and Vietnam centered around a concept of integrated deterrence, and a call for China to scale back military action in the region.

A China Review Panel is due to release a set of strategic recommendations this Fall. A broader defense strategy from the administration is also in the works. Those will inform formal DOD plans on what resources we’ll move around the globe, and that itself follows an earlier memo by Defense Secretary Austin in June on closing what has by now been referred to as a ‘say-do gap’ between what the military says it should do on China and what it’s actually doing.

So, we’ve got Obama administration alums in many senior national security positions, many of whom felt burned by falling short of the ‘pivot to Asia’ in their prior turn in government. And instead of quick action, we’ve got strategies and panels; we’ve got reviews and councils, but do you know what we don’t have?

An actual plan to complete the pivot to Asia that we’ve been hearing about since 2011. Nor do we have the urgency required on this issue, and that’s true of policymakers on both sides of the aisle save for some tough questions on Capitol Hill. I mean this criticism not as an easy jab at a burdensome interagency process, but instead because there are two traps we may very well fall into if we’re not careful:

-That much of Washington now sees the pivot as simply a continuation of normal statecraft, versus a necessary and required strategic reorientation of our security posture that has not yet occurred. Just focusing on China more as it grows is different than making a grand shift in our security posture with a resulting step change in world affairs.

-That the pivot was, and will be, used by some as a rhetorical cudgel to continue American disengagement around the world or to satisfy a yearning for an imagined more traditional, cleaner era of great power conflict.

The Washington consensus has for years been that the most important thing to do is pivot to Asia, and the reason we couldn’t is that we were keeping a few thousand troops in Afghanistan and Iraq. But now we’re gone: out of Afghanistan and in Iraq only 2,500 in non-combat roles.

But what and where are our firm commitments in Asia? Which money, men, and materiel now freed up are heading where? Are we committing to 60% of our naval assets to remain in the region, as the Obama administration at one point signaled? We need specifics and to ask the Biden administration if they think may be waiting a year into a four-year tenure to get any of this in motion is not the right pace.

More importantly, we need to hear from this administration not just what the plans are to move the chess pieces around, but the explicit state-change we intend to produce. Which Vietnamese or Filipino fishing trawlers will go un-harassed by Chinese army-affiliated vessels? If China tries to build new military bases in international waters, will the United States prevent that from happening? If so, how?

These questions need to be put to the President and the Press Secretary, but they also are answerable by the American people too. We need to – and soonest – have our own discussion as to whether we actually support a beefed-up presence in Asia and aggressive participation in great power politics, or whether we cheered on this language, advanced by both parties, in service of further isolationism. Put more simply, are we willing to embrace and stand by our alliances when they require backing in blood or did we just mean this whole pivot stuff as a way to get out of the Middle East?

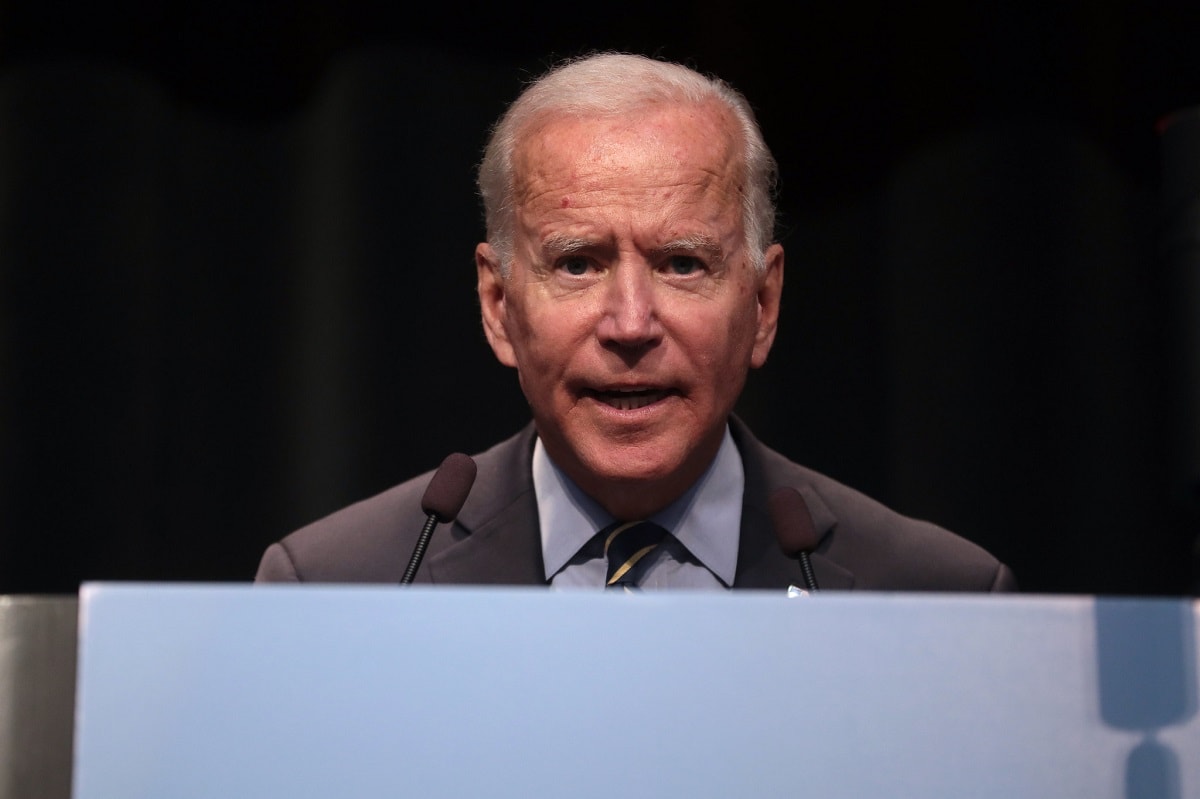

Image: Obama White House Flickr.

A lack of general curiosity as to the mechanisms and manifestations of a ‘Pivot to Asia’ in the wake of the withdrawal from our long wars suggests it may be the latter. In Part II of this piece, I’ll explore the idea that regardless of our answer there are some tough conversations ahead if we want to avoid greater conflict.