Would the Cold War have been hotter? Would fifty thousand American soldiers have lost their lives? Would today’s Americans worry that North Korean nukes will land on their heads?

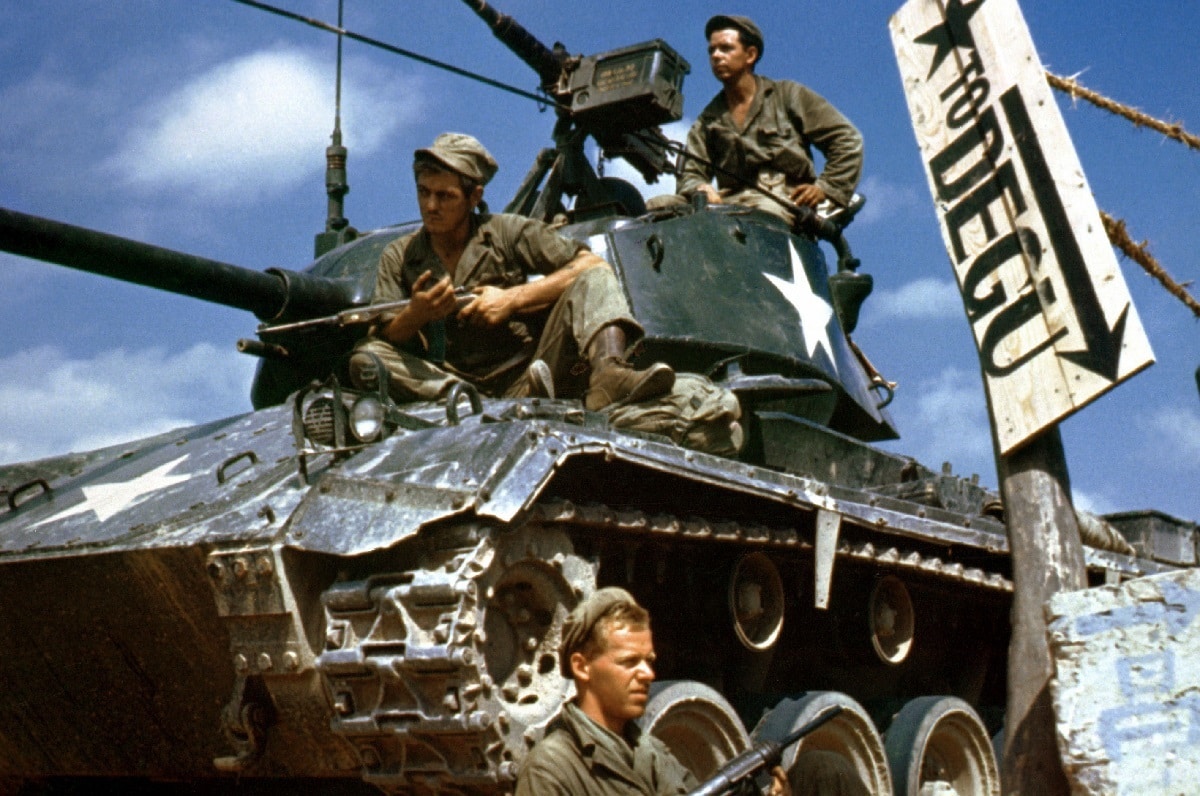

The problem with counterfactual history is that it’s often pointless to speculate or the speculation is crazy. But a North Korean victory was more than within the realm of possibility. Kim Il-sung’s army came tantalizingly close to victory in August 1950, when its Soviet-supplied tanks flattened the outgunned and demoralized South Korean troops. Much of the South was captured, before hastily deployed U.S. troops and South Korean remnants barely held onto a bridgehead around the port of Pusan.

Then in September came the U.S. Marine landing at Inchon, and the UN counteroffensive that sent the North Koreans reeling back north across the thirty-eighth parallel. But what if the Marines had never been sent to Korea? The Marines were only there because the Soviet UN ambassador boycotted the Security Council over the issue of Taiwan having a UN seat instead of Communist China. If he had been present, he could have vetoed the first-ever UN resolution authorizing force.

Without a UN mandate, the Truman administration might have balked at sending troops unilaterally. In 1941, U.S. troops had embarked on a crusade against fascism. In 1950, they were fighting a “police action” against aggression (as Alan Alda asked in M*A*S*H: if Korea was a police action, where were the cops?).

In fact, the United States didn’t care that much about South Korea until the Communists invaded it. In January 1950, Secretary of State Dean Acheson had omitted South Korea from a speech defining which territory was included in America’s Asian defense perimeter. Truman and his advisers also worried that the North Korean invasion was just a Soviet decoy to divert U.S. troops from defending Western Europe.

Thus, there were numerous reasons why the United States could have chosen not to intervene in Korea, and concrete reasons why South Korea would have been conquered without that intervention.

Then there is the question of China. There were really two Korean Wars: the initial North Korean invasion in August 1950, and the Communist Chinese offensive that began in November 1950. The three-hundred-thousand-strong Chinese force routed U.S. and UN forces out of North Korea, surged back across the thirty-eighth parallel and captured Seoul before the offensive petered out. The Chinese armies lacked the logistics to overrun all of South Korea. But in that panicky “Bug-Out” winter of 1950–51, it’s not totally impossible that the United States and UN could have chosen to evacuate their forces from the peninsula.

In that case, we again end up with the two Koreas unified under one Communist government based in Pyongyang. What would have this meant for the Korean people? Good and bad, according to scholar Andrei Lankov. There would have mass repression in the South, but military victory and the absence of a hostile South Korea on its border might have made the regime a bit less murderous.

A less paranoid North Korea might also have been more open to Chinese-style economic reforms, Lankov believes. And perhaps North Korea would have felt less of a need to develop nuclear weapons or ICBMs. Still, Korea would have been united under rulers who could sleep soundly at night while their people ate grass to survive.

The question of Communist victory in Korea inevitably leads to the question of Communist victory in the Cold War. Cruel as it sounds to those who died in the mountains and snow and mud, the Korean War was never about Korea. What counted wasn’t Korean security, but the security of Western Europe, Japan and Communist China.

Defeat in Korea would have focused American eyes on Japan. With Truman already under attack by U.S. conservatives for allegedly losing China to the Communists, a North Korean victory would have spurred fears of Soviet invasion or subversion of Japan, which in turn might have led to a deeper U.S. security commitment in Asia.

Certainly a North Korean victory would have stoked American fears over what it saw as a global Communist conspiracy to enslave the world. In fact, Kim Il-sung invaded South Korea with Stalin’s approval rather than at his command. Whether success in Korea would have emboldened Stalin or Khrushchev, we’ll never know.

Nor can we know whether the United States would have felt compelled to act more forcefully during crises such as Berlin or Suez. Would a superpower wounded in prestige and self-respect by the loss of Korea have been more likely to pull the trigger next time?

Indeed, North Korea triumphant might have led the U.S. to adopt an early version of the Domino Theory. Just as the Korean War erupted, so did the Communist insurgency in French Indochina. As the French struggled against the Viet Minh, the United States might have heeded calls to provide air support (including nuclear weapons) to support the French defenders of Dien Bien Phu. Or, the United States might have committed troops earlier than 1965 to prop up the Saigon government.

Korea was “the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy,” General Omar Bradley famously declared in May 1951. Or was it the right war? Preventing a Communist victory in Korea might have been the circuit-breaker that stopped World War III.

Michael Peck is a defense writer based in Oregon. He can be found on Twitter.