On the morning of September 15, 1950, as US and Royal Navy warships fired at targets ashore, US Marines boarded landing craft and assaulted Wolmido, a small fortified island at the mouth of Incheon harbor.

The North Korean invasion three months earlier had devastated the South Korea army, pushing it into a last bastion in the southeastern corner of the peninsula.

The Marines landing at the port of Incheon were part of a 40,000-strong landing force with a critical objective: liberate the city and open a second front.

It was the largest amphibious invasion since D-Day, and like that operation, it would turn the tide of the war. Nothing less than the fate of South Korea was at stake.

Pusan Perimeter

The situation in South Korea in September 1950 was perilous. The North Korean offensive launched on June 25 was too strong for South Korea’s military to fight off alone, and Seoul was captured in just three days.

On June 27, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 83, which condemned the North Korean action as a “breach of the peace” and called for the world to assist South Korea. Resolution 84, passed on July 7, designated the US as the leader of military operations to save South Korea.

Ultimately, 21 countries contributed to the US-led effort. It was the Cold War’s first hot conflict.

The first American soldiers arrived in early July, but due to equipment and supply shortages as a result of the downsizing of the US military after World War II, they were unable to reverse North Korea’s gains.

By August, communist forces held all but a 100-mile by 50-mile area around the port city of Busan that was known as the “Pusan Perimeter,” where UN and South Korean forces desperately held off repeated KPA attacks.

‘I shall crush them’

Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the famed American general in charge of UN forces in Korea, knew the pressure needed to be taken off the Pusan Perimeter.

He devised a bold plan for an amphibious operation to land thousands of troops at Incheon — 150 miles behind enemy lines.

Incheon was on the opposite side of the peninsula and only 20 miles from Seoul, which meant UN forces could land, liberate the capital, and launch a pincer attack that would surround the KPA on two sides.

It would not be easy. Incheon’s tide fell as much as 36 feet twice a day, exposing completely impassable mudflats for 12 hours. Moreover, the city had seawalls as high as 12 feet in some places, and the KPA had turned Wolmido into a fortress.

Troops assaulting in the morning waves would have to wait 12 hours for reinforcements, and those arriving in the evening would have only 30 minutes of daylight to secure their objectives.

“We drew up a list of every natural and geographic handicap — and Inchon had ’em all,” one staff officer wrote later.

“Make up a list of amphibious ‘don’ts,’ and you have an exact description of the Inchon operation” another officer recalled.

MacArthur was undeterred. He knew such an operation would be “sort of helter-skelter” but believed it would be the kind of surprise that could win the war.

“We must act now or we will die,” he told his staff at a planning conference. “We shall land at Inchon, and I shall crush them.”

Operation Chromite

MacArthur’s plan, dubbed “Operation Chromite,” was approved and assigned a massive force of 40,000 men and 230 ships.

UN aircraft and warships bombed and shelled cities, bridges, and railways across Korea in the weeks before the battle, hoping to distract the KPA from the true target.

Air attacks on Incheon began on September 10. On September 13, two days of naval bombardment began, with particular attention to Wolmido, the first target for capture. Despite the intensity of the bombardment, three destroyers were damaged by return fire from coastal artillery.

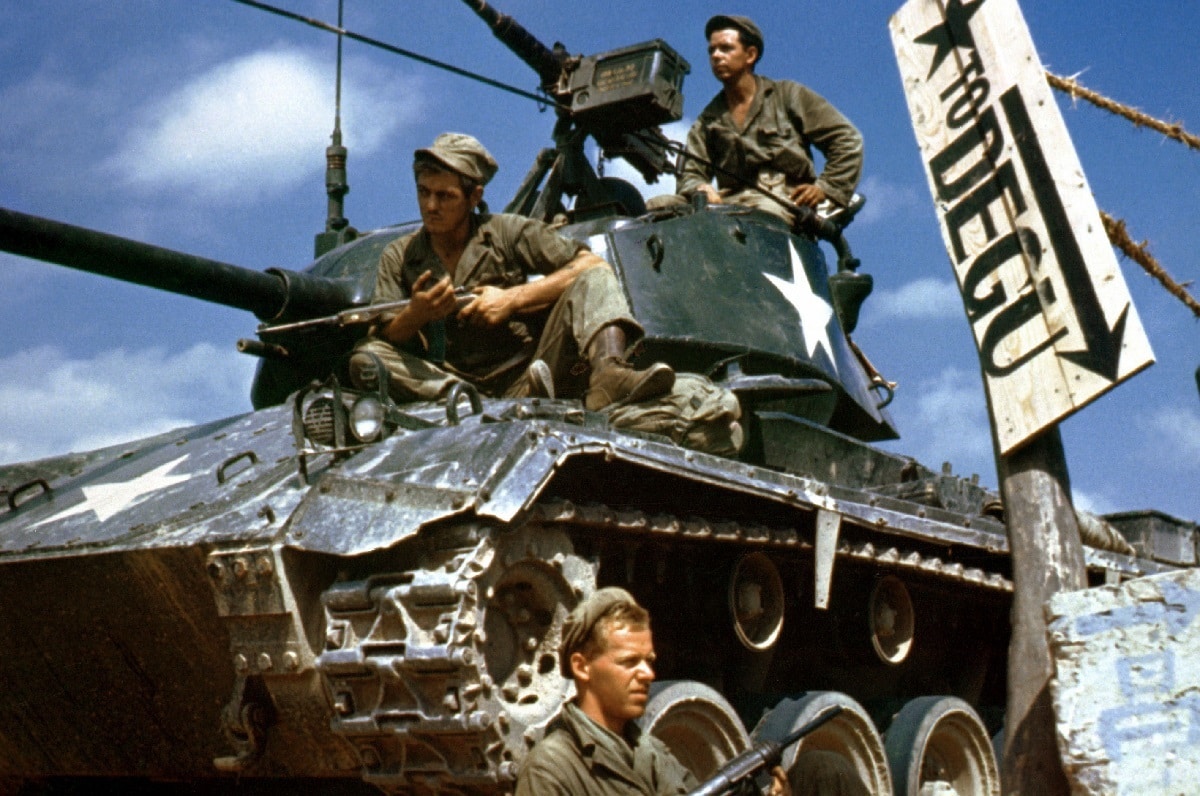

On September 15, the first landing craft arrived at Wolmido. With support from 10 tanks, the Marines were able to quickly take the island with only 17 wounded.

They waited 12 hours before the second wave arrived, which landed Marines at beaches north and south of Incheon. As the Marines pushed into the city, they were constantly supported by fire from cruisers, destroyers, and aircraft carriers.

The Marines were able to secure the harbor by September 16. There were a few pockets of heavy resistance during the initial landings but mostly light resistance in the city itself. US troops quickly moved to the surrounding hills, taking Kimpo Airfield on September 18 and turning it into an airbase.

The KPA were completely surprised, and the diversionary tactics added to the confusion. The KPA sent tanks to slow down the Americans, but they were no match for UN forces. By September 19, Incheon was secure.

Three more years

Operation Chromite was a massive success. With Incheon liberated, UN forces headed to Seoul. It was retaken within two weeks of the landings, despite desperate KPA resistance.

The invasion of Incheon and liberation of Seoul resulted in about 3,500 casualties for UN forces. KPA casualties, meanwhile, were estimated to be roughly 14,000 dead and 7,000 captured.

The KPA was outflanked and soon forced into complete retreat. On September 23, UN forces at Pusan began pushing north to link up with troops at Incheon and Seoul.

Allied airpower, operating from Kimpo, other airfields in South Korea, and Japan, as well as from nearby carriers, continued to attack KPA positions virtually unchallenged.

By the end of September, the remnants of the KPA had retreated back across the 38th Parallel. It was a stunning reversal, but the war was far from over.

MacArthur, buoyed by his victory and determined to push the communists out of Korea, was allowed to advance north of the 38th Parallel.

Worried about the loss of an ally, the Soviets and Chinese increased their support. The Chinese officially joined the war in October, and Soviet fighter pilots began engaging UN aircraft in November.

There would be another three years of bloodshed before the war ended in a stalemate that persists to this day.

Benjamin Brimelow is a reporter at Business Insider.