General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev dissolved the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on Christmas day 1991. In the two succeeding decades, the Communist Party of China, mindful of the Soviet demise, was implementing policies prolonging its rule and thereby postponing the USSR’s fate.

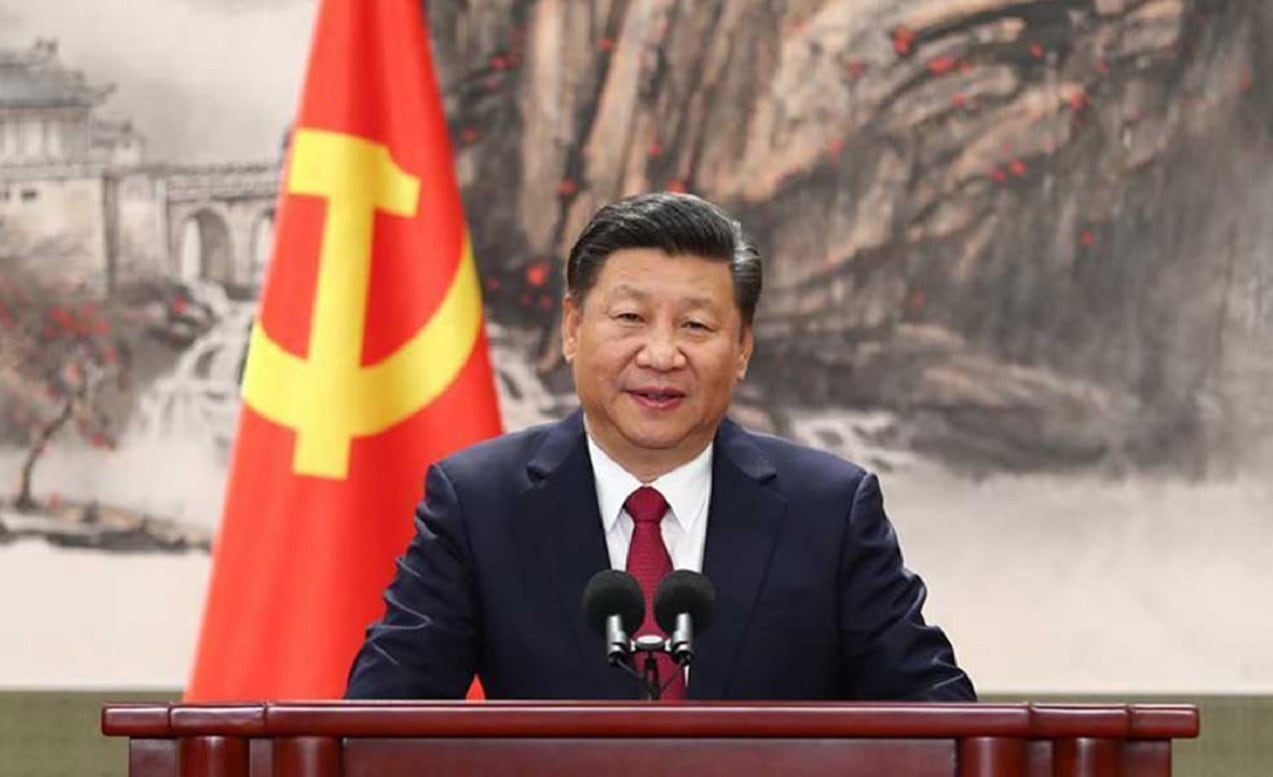

Yet in the past decade, under General Secretary Xi Jinping, China’s ruling party has reversed course. As a result, some see signs of decay. “The situation with the Chinese Communist Party today is in many ways directly comparable to that of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s,” Gregory Copley, editor-in-chief of Defense & Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy, tells 1945.

Most observers believe Gorbachev took over a near-corpse and had to do something. Yet most everyone also realizes his bold policies of glasnost, openness, and perestroika, restructuring, ultimately hastened the end of the Soviet state.

Certainly, Xi Jinping blamed Gorbachev. “Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Soviet Communist Party collapse?” Xi asked in a secret speech to Guangdong province cadres in December 2012, one month after being named general secretary at the 18th National Congress. “An important reason was that their ideals and convictions wavered.”

“Finally, all it took was one quiet word from Gorbachev to declare the dissolution of the Soviet Communist Party, and a great party was gone,” Xi declared. “In the end, nobody was a real man, nobody came out to resist.”

Xi’s address has been called a “new southern tour speech.” Deng Xiaoping, Mao Zedong’s eventual successor, signaled the restarting of economic reforms in 1992 with highly symbolic visits to Shenzhen and other Guangdong locations.

Deng, who promoted “reform and opening to the outside world,” believed that Chinese communism would not survive the wreckage of the Maoist years without delivering prosperity and that prosperity would not come without economic liberalization. He probably did not say “to get rich is glorious”—a phrase often attributed to him—but he did in fact utter these words: “poverty is not socialism.”

It cannot be a coincidence then, that Xi Jinping chose Guangdong for his December 2012 speech. Xi’s regressive words embraced the policies of the first Chinese Communist supremo, whom the current leader reveres. Deng believed he was saving Chinese communism from Mao while Xi believes he is saving Chinese communism from Deng.

Why did Soviet communism fail? Many analysts point to its grossly inefficient economic system, which could not keep up with American-style capitalism.

Yet there was an even more fundamental reason. “The core of the Soviet system was control over people’s minds,” David Satter, a Russia scholar, and author, told 1945. “As soon as the system, in a misguided attempt to reform itself, opened a space for the truth, the collapse of a system based on lies was inevitable.”

Deng’s reforms created prosperity, but they also created power centers not beholden to the Communist Party. More importantly, they created hope among common Chinese that the country would loosen political controls. As such, the reforms undermined acceptance of Marxist ideology and eroded the legitimacy of the Party and its control over society. The massive demonstrations in the Chinese capital and hundreds of other cities during the Beijing Spring of 1989 were largely the result of people sensing the possibility of change and therefore demanding it.

Deng’s response to the widespread protests—the wholesale killing of Chinese citizens to demonstrate the determination of the Communist Party to keep power—prolonged its rule, but his two successors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, did their best to cover up Deng’s murderous response, thereby undoing the effect of his lesson. Consequently, the Chinese people, who were losing fear of the Party, began, once again, to reject its orthodoxy.

Xi Jinping demands acceptance of that orthodoxy, something evident in his Maoist-inspired “common prosperity” program. He is reversing reform by attacking the private sector, reinstituting totalitarian social controls, demanding absolute political obedience, and cutting foreign links. Closing China off from the world is an essential element in Comrade Jinping’s attempt to save communism. “Xi is embracing the failed Soviet model,” Copley notes.

Xi is borrowing from a well-used Chinese playbook. His isolationism and xenophobia evoke policies from the earliest years of the People’s Republic and during the two millennia of imperial rule. As Georgia Tech’s Fei-Ling Wang details in The China Order: Centralia, World Empire, and the Nature of Chinese Power, isolationism is inherent in Chinese totalitarianism.

Chinese rulers, as Arthur Waldron of the University of Pennsylvania told the Hoover Institution, have periodically avoided contact with other societies “lest that lead to disorder, as globalization is doing in China today.” These rulers throughout history relentlessly enforced their geliguojia—“separated country”—system, he points out. Today, Xi Jinping is going back to that approach.

Of course, as Chinese leaders closed off China from time to time, economic stagnation and failure inevitably followed. At the moment, the Chinese economy is probably contracting, mostly the consequence of Xi’s misguided views.

There is no way to save Chinese communism. Deng failed with openness. Xi Jinping is now failing with isolationism. Chinese leaders always tell us their regime is unique, so call it failure with Chinese characteristics.

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China and The Great U.S.-China Tech War. Follow him on Twitter @GordonGChang.