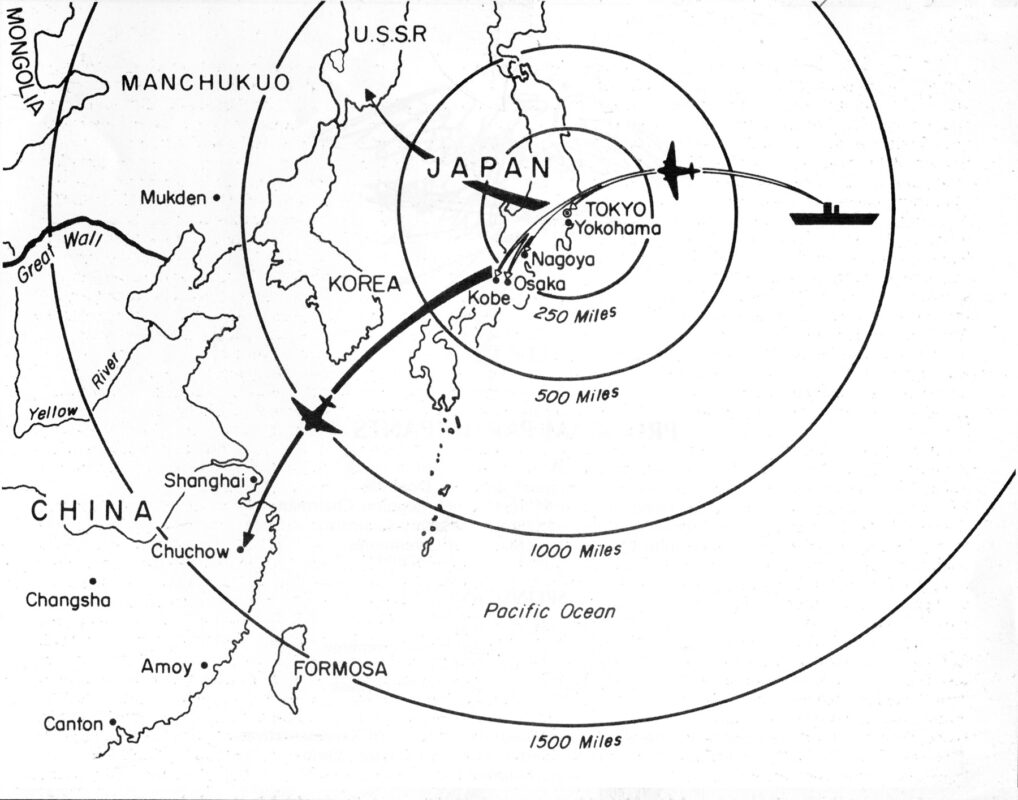

The Doolittle Raid was revenge for Pearl Harbor: On the April 18, 1942, sixteen B-25B Mitchell medium bombers, each with a crew of five, were launched from the United States Navy aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) and began a mission meant to avenge Pearl Harbor. The bombers were the first to conduct an air operation to strike Japanese cities including Tokyo, Kobe, Yokohama and Nagoya. The raid was planned and led by Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle.

Also known as the Tokyo Raid, the Doolittle Raid as it is more commonly remembered as, actually did comparatively minor damage – yet it demonstrated that the Japanese main island of Honshu was vulnerable to American air attacks.

Preparing for the Flight

Given the fact that the United States Army Air Force bombers had to take off from a carrier – something that had never been done before – and fly some 2,400 nautical miles, the B-25 Mitchells had to be specially modified. The range of the B-25 was just 1,300 nautical miles, so the bombers were modified to carry nearly twice the normal fuel.

The crews had been detailed to Eglin Air Base, Florida, for intensive training in March 1942 with Navy pilots who demonstrated carrier takeoff and landing procedures. The Army aircrews practiced on a stretch of runway painted to simulate a carrier flight deck, which was only 500 feet (152 meters) long.

As the bombers had been loaded onto the carrier deck by cranes and couldn’t return to the Hornet, the raiders had to complete their bombing runs against industrial targets in the cities and then fly on to land at friendly airfields in China. On April 1, 1942 the crews boarded the carrier at Alameda Naval Air Station in San Francisco Bay. As the bombers were too large for stowage on the hangar deck, the aircraft were lashed to the flight deck.

After boarding USS Hornet, Doolittle addressed the raiders, “For the benefit of those who have been guessing, we are going to bomb Japan. The Navy will get us as close as possible, and launch us off the deck.”

Doolittle asked if any of the men wanted to back out of taking part. Not a single one did.

Each of the bombers carried four specially constructed 500-pound (225kg) bombs, three of which were high-explosive munitions and one included a bundle of incendiaries. Five of the bombs also had Japanese “friendship” medals wired to them – awarded by the Japanese government before the war.

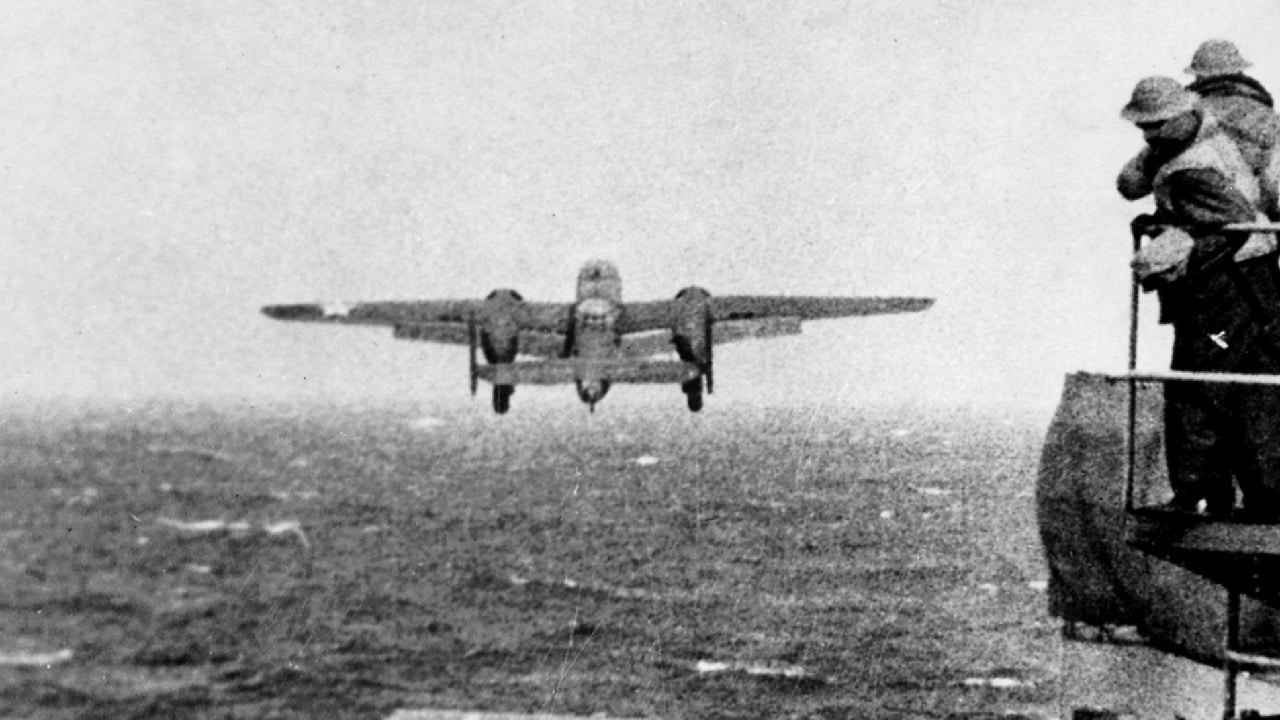

The Raiders Take Flight

On April 18, at 7:38 am, USS Hornet and Task Force 16 were approximately 650 miles off the Japanese coast when a Japanese 70-ton patrol boat, No. 23 Nitto Maru, was sighted. The U.S. Navy light cruiser USS Nashville went to battle stations and sunk the patrol boat but the Americans were unsure if the Japanese sailors had sent a warning.

While they were 200 miles further from Japan and it was ten hours earlier than planned, the decision was made to launch the strike.

In a photograph found after Japan’s surrender in 1945, Lt. Robert L. Hite, copilot of crew 16, is led blindfolded from a Japanese transport aircraft after his B-25 crash-landed in a China after bombing Nagoya on the the “Doolittle Raid” on Japan and he was captured. He was imprisoned for 40 months but survived the war.

The first Mitchell was piloted by Doolittle and left the flight deck of USS Hornet at 8:20 am, followed by the remaining aircraft in three-minute intervals. The aircraft reached the home islands and climbed to 1,200 feet in clear skis. The U.S. raiders were under specific orders to avoid dropping their payloads on the Imperial Palace, the residence of Emperor Hirohito, or any civilian targets including schools, markets or hospitals.

The raid completely took the Japanese by surprise. Air defense was virtually non-existent as the bombers reached their targets. Material damage was light, but it proved that Japan could be hit. Until that April morning, in fact, Japan considered the home islands inviolable.

As the aircraft flew on to China, several B-25s were shot down or crashed, while combat damage forced some of the surviving B-25s to head to the nearest neutral territory rather than to the planned bases in China. Little may have actually been gained militarily from the raid, but it demonstrated to the American people that the U.S. military could strike back.

Notable B-25 Mitchell Facts

The Doolittle Raid was not actually the combat debut for the B-25 Mitchell. The aircraft had been used in the early stages of the war on antisubmarine patrols, and a B-25A scored the first “kill” for the bomber on Christmas Eve, 1941, when it attacked and sunk a Japanese submarine off Puget Sound on the United States’ West Coast.

Map showing Doolittle Raid targets and landing fields. Doolittle Raid was an air raid by bombers from an American carrier on Tokyo and other places in Japan on 18 April 1942 , four months after Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor.

Named for the forward-thinking aviation pioneer U.S. Army Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell, the charismatic airpower prophet who proved in 1921 and 1923 that planes could sink battleships, the B-25 Mitchell gained an unsurpassed reputation as a ground-attack bomber and ship killer.

The rugged and highly versatile B-25 saw action on almost every Allied front, from the Mediterranean to the Pacific, and from Burma to Normandy, and was regarded by many as the most successful twin-engine combat aircraft of World War II.

Now a Senior Editor for 1945, Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers and websites. He regularly writes about military hardware, and is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress, which is available on Amazon.com. Peter is also a Contributing Writer for Forbes.