The Hunt for Red October, starring the late great Sir Sean Connery, was a huge hit with film critics and moviegoing audiences alike. K-19: The Widowmaker, starring Harrison Ford and Liam Neeson, was not as successful with either critics or at the box office, but nonetheless remains an entertaining and memorable film about a Cold War-era Soviet nuclear submarine. A big plus about the latter film is that it’s based on a true story.

In fairness, yes, the late great Tom Clancy also did base his original bestselling novel very loosely upon a true story, but in that real-world instance, the Storozhevoy was a surface ship, not a submarine, and what’s more, the mastermind, Valery Sablin, was a dyed-in-the-wool Communist, not a freedom-seeking defector.

However, as is typical of Hollywood, even when they tell a “true” story, they embellish it for entertainment purposes. With that in mind, let’s take a deeper dive (bad submarine pun intended) into the real story of the K-19 and see where the filmmakers deviated from reality.

Hollywood Hokum

Harrison Ford bears a fairly passable resemblance to the real-life skipper of the K-19 during the vessel’s 1961 maiden voyage, and the rank of Captain 1st Rank (the equivalent of an O-6/Captain in the U.S. Navy) was correct. But the real-life Captain’s name was Nikolai Vladimirovich Zateyev, not Alexei Vostrikov. Zateyev was considered to be an ambitious and capable officer by his superiors, as affirmed by his early promotion from Marshall Georgy Zhukov (then-Defense Minister of the USSR) at the young age of 32.

Capt. Zateyev’s published memoirs did in fact serve as part of the source material for the movie. Moreover, the normally heavily fact-oriented National Geographic Society was involved in the production of the film. NatGeo even hired one of the nation’s leading experts on Cold War submarines, retired U.S. Navy Capt. Peter Huchthausen, as a technical adviser. Capt. Huchthausen also authored the non-fiction book that was published as a movie tie-in.

But that didn’t stop the filmmakers from taking some liberties. For one thing, whilst The Widowmaker may have been a catchy film subtitle, and while the real-life crew of the K-19 did indeed consider the boat to be cursed, their actual nickname for it was “Hiroshima.” I suppose the use of “Hiroshima” as the movie’s subtitle might’ve confused audiences into thinking it was a WWII film.

In addition, as noted by Chicago Tribune columnist Michael Kilian, “But Hollywood couldn’t resist a few embellishments. In a long sequence, the producer and director have a U.S. destroyer, shadowing the surfaced K-19, launch a helicopter to take a look at it close up. Stealing a scene from ‘Braveheart,’ they have the Russian crew bare their behinds to the chopper to show contempt (is this going to become a cliche of all war movies?). Fine, but for one thing: U.S. destroyers in 1961 didn’t carry helicopters…’I told them we didn’t have helicopters on destroyers in 1961, but they kept it,’ Huchthausen said. ‘We depicted everything we knew had happened. The only departures from the real fact are what the movie’s director and producer thought they had to do to make it a little more sensational.’“

Indeed, many of the real-life survivors of the K-19 incident were unhappy with the film’s script, and quite a few of their countrymen complained that the timing of the film – released in 2002 – was exploitative of the Kursk tragedy that had transpired two years earlier – a key difference, of course, being the fact that none of the Kursk‘s crew lived to tell their tale.

The Story Behind the Story

Since Capt. Hutchhausen’s book isn’t available on Kindle and therefore I don’t have it handy for reference on such short notice, let us instead turn to sources such as a declassified NSA analysis – which still has multiple redactions – for some objective facts.

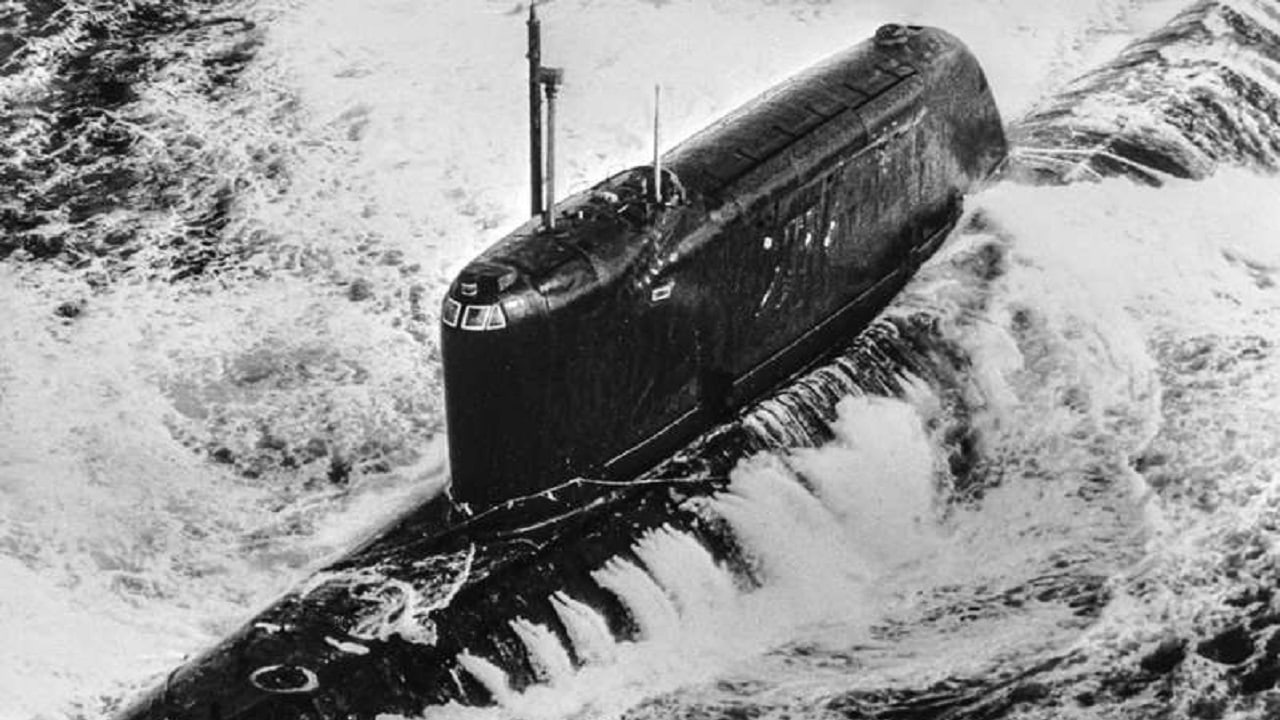

The K-19 was the first boat in the Soviet Navy’s Projekt-658 class of submarines, which were given the NATO reporting name of Hotel-class submarines. In turn, the Hotel class was the USSR’s first generation of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). The Hotel-class subs were roughly 350 feet (106.68 meters) long and 30 feet (9.14 meters) wide, with a surface displacement of 4,095 tons and a submerged displacement of 5,080 tons. They had a max speed of 15 knots surfaced and 26 knots submerged and were powered by two pressurized water nuclear reactors capable of generating 70 megawatts.

K-19 had her keel laid in the Severodvinsk shipyards on the White Sea on 17 October 1958, was launched on 8 April 1959, and commissioned on 12 November 1960. In the Soviet hierarchy’s rush to get their first SSBN operational, they cut corners in terms of safety inspections and quality control, as was already evident during the sea trials: “An omen of bad things occurred in February 1961 when an unexplained loss of pressure occurred in the first containment system of one of the reactors.”

This would come to a head during the sub’s first operational tour, which took place from June to July 1961. On the 4th of July – yes, the birthday of the Soviet Union’s “capitalist” rival nation, of all days – one of the pipes that regulated the pressure for the coolant system of one of K-19′s two reactors burst. As the declassified NSA report continues, “An engineering oversight had put the pipe in an inaccessible spot. No one could reach it and repair the leak. (Other reports claim that the port-side pump that provided cooling for the heat exchanger broke down.) The crew had to jury-rig a system for cooling the reactor. The radiation that leaked out was estimated to be about 5 roentgens an hour – any crewmen working in the area would receive a dangerous dose after that time.”

Aftermath

By the time the crew was finally rescued by another Soviet sub participating in the training exercise, eight of K-19’s 139-man crew had perished, with 15 more sailors dying over the next two years. The sub herself would continue to be plagued with bad luck until her decommissioning in 1990. The surviving crew were sworn to secrecy and unable to finally tell their stories until 1991, the final year of the Soviet Union’s existence. Capt. Zateyev passed away from lung disease on 28 August 1998, at the age of 72. Seven-and-a-half years after his passing, Capt. Zateyev and his crew were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, whose glasnost (“openness”) policy had made it finally possible for the K-19‘s crewmen to share their stories in the first place.

Christian D. Orr is a former Air Force officer, Federal law enforcement officer, and private military contractor (with assignments worked in Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kosovo, Japan, Germany, and the Pentagon). Chris holds a B.A. in International Relations from the University of Southern California (USC) and an M.A. in Intelligence Studies (concentration in Terrorism Studies) from American Military University (AMU). He has also been published in The Daily Torch and The Journal of Intelligence and Cyber Security. Last but not least, he is a Companion of the Order of the Naval Order of the United States (NOUS).