A top-tier defense expert breaks down the ADM-160 MALD, and how the U.S. military could put at risk any nation’s air defense platforms in a war – that means of course Russia or China: The ADM-160 MALD, or Miniature Air-Launched Decoy, is exactly what its name suggests: a small vehicle that’s launched by aircraft, like a cruise missile, that can mimic the radar returns of any American aircraft in service. While the various iterations of the MALD can’t destroy enemy surface-to-air missiles, they can play a huge role in helping to eliminate even the most advanced integrated air defenses on the planet.

The nine-foot-long, 300-pound MALD manages this feat via a Signature Augmentation Subsystem (SAS), which leverages active radar enhancers that broadcast across a wide range of frequencies to fool defensive radar systems into mistaking the missile-shaped MALD for jets ranging from the original gangster of stealth, the F-117 Nighthawk, all the way up to massive payload-ferrying bombers like the B-52.

The MALD effort began in the 1990s, following America’s success in the Persian Gulf War deploying more than a hundred ADM-141 Tactical Air-Launched Decoys into Iraq ahead of coalition aircraft to fool Iraqi commanders into activating their air defense radar arrays. Once the enemy radar systems came online, coalition aircraft engaged them with anti-radiation missiles like the AGM-88 HARM, making for an extremely effective means of rendering Iraqi airspace safer for subsequent air operations.

MALD development slowed in the late 1990s, however; hindered to some extent by the goal of keeping system costs low. By 2002, the Air Force was ready for a new take on the MALD concept, scrapping the $30,000 ADM-160A in favor of a new competition that would result in Raytheon’s larger and more capable ADM-160B, carrying a per-unit price tag of $120,000.

By 2016, the ADM-160C MALD-J was officially in service, incorporating not only the Signature Augmentation Subsystem of the original that can mimic the radar returns of other aircraft, but also a modular electronic warfare capability developed under the name CERBERUS. Rather than a single jammer, CERBERUS offers a variety of interchangeable electronic warfare (EW) payloads that can be swapped in and out in less than a minute, allowing for tailored EW attacks for a variety of battlefield conditions.

In other words, the small and expendable MALD-J, currently carried into the fight by either F-16s or B-52s, is capable of fooling enemy air defenses into thinking they’re all sorts of incoming aircraft, and can also jam early warning and targeting radar arrays to further complicate matters for defending forces.

While not as broadly capable or as powerful as dedicated electronic warfare aircraft like the Navy’s EA-18G Growler, the MALD-J’s ability to swap EW payloads for increased effect still makes it a highly effective system. And because the MALD is non-recoverable (or expendable), it can fly much closer to defending systems than any Growler would, offsetting its reduced broadcast range by simply flying closer to the target.

The MALDs in service today can cover 500 miles and remain airborne for over an hour, all the while complicating matters for any radar operators in the area. The newest iteration of the system, the MALD-X, incorporates even more advanced EW capabilities alongside an encrypted data link that will allow it to take cues from other platforms, shifting from a pre-programmed asset to a dynamic one capable of playing a more active role in combat operations.

Previously, after a MALD was launched, it would fly along a pre-programmed flight path based on intelligence gathered prior to the mission, regardless of how effective that path proved to be. Now, however, the MALD-X will be able to take commands during mid-fight, adjusting its flight path to suit the changing battlefield environment. This evolution of the system completed free-flight test demonstrations in 2018. The MALD-X is meant to eventually lead to a new iteration of the system meant for the Navy, dubbed the MALD-N.

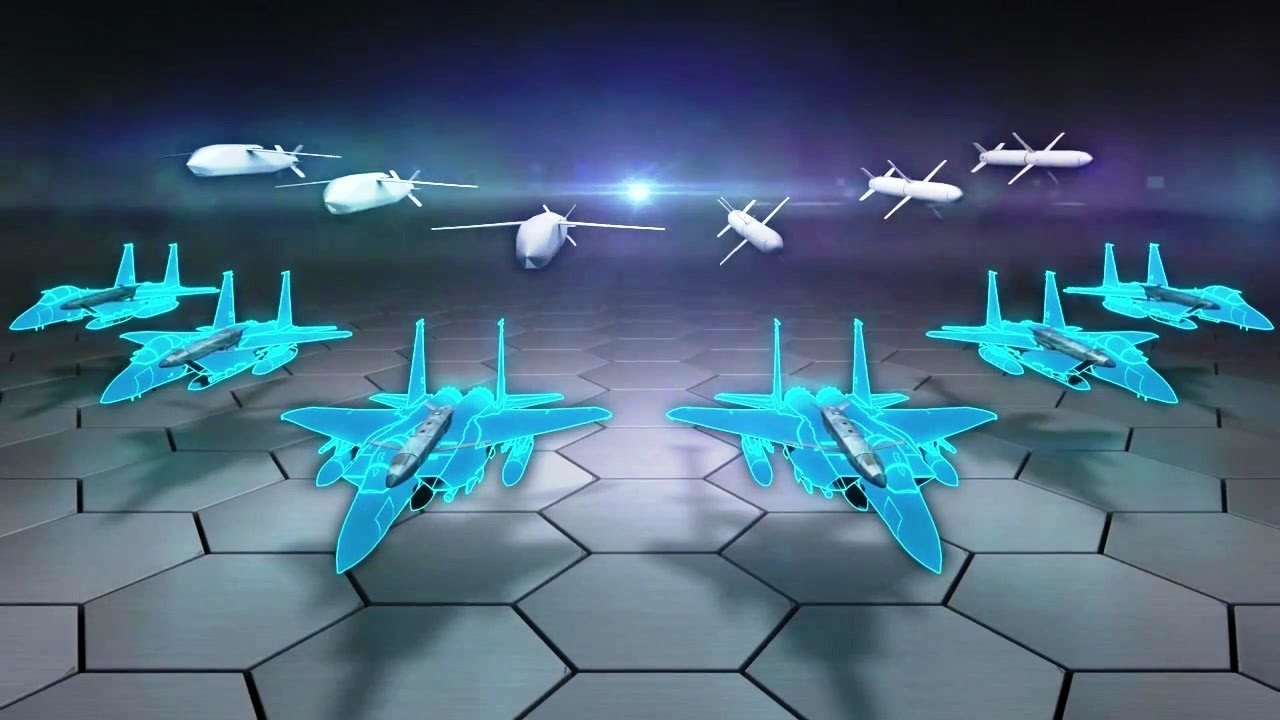

In a large-scale conflict against a country with substantial air defense capabilities, there is a high likelihood that the ADM-160C MALD-J would be among the first American assets to cross into enemy airspace. By deploying a high volume of these jamming decoys into a contested area alongside cruise missiles and aircraft, air defense systems would be forced to try to divine the difference between real and fictional radar returns on their scopes, and all while sifting through a stream of static delivered by the system’s jamming capabilities.

Launching interceptors at the flood of real and simulated radar returns pouring into enemy airspace would leave these systems vulnerable to attack from anti-radiation missiles like the AGM-88 or the more advanced AARGM-ER, soon to be carried internally by F-35s, while simultaneously depleting their surface-to-air missile stores.

In more limited engagements, a formation of MALDs presenting the returns of F-15E Strike Eagles closing in on a potential target, as one example, could draw a great deal of focus while stealthy F-35s flying at higher altitudes deploy munitions at the same target.

By mixing combat tactics and using MALDs to replicate tactics leveraged in previous real attacks, the efficacy of these systems could remain high even deep into a conflict. Put simply, ignoring an encroaching swarm of fighters or bombers on your radar screen is just too risky, even if they prove to be nothing more than decoys some of the time.

Mix in some long-range low-observable cruise missiles like the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM), which can be lobbed into the fight by A-10s, B-52s, a variety of fighters, or in larger groups by cargo aircraft thanks to programs like Rapid Dragon, and you’ve created a terrifying swarm of real and fictional threats that even the most advanced integrated air defense systems on the planet couldn’t hope to effectively manage.

The use of the MALD as a part of a broader combined strategy could allow the United States to return to an approach to air warfare that’s somewhat reminiscent of the bombing raids of World War II — where defeating the enemy’s air defenses was more a question of volume than successful tactics. Except in a modern fight, most of the targets that would actually appear on enemy radar screens wouldn’t be real, and the most pressing threats from stealth aircraft or cruise missiles may not appear on targeting scopes at all.

And that’s a very difficult problem for any opponent to solve.