After over a decade in the making, the Army’s new fitness test has arrived. And at a moment when the U.S. Army is facing tough competition from Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, and many other nations, it could help the service get in fighting shape. Or will it?

On Saturday, the Army‘s new fitness test becomes official after nearly 12 years in development, marking the first time since soldiers began training for the new standard two years ago that they will have their strength and endurance formally held up to the new benchmarks.

A staple of military service, the fitness test has effectively been sidelined as officials tuned it and soldiers got familiar with revamped, more difficult fitness routines. The test becomes official for part-time National Guard and Reserve soldiers in April.

The Army Combat Fitness Test, or ACFT, has been a heated topic among troops, the media and Congress as the service effectively developed much of the test in public, seeking feedback in real time. Soldiers initially blasted the test for being overly complicated and a logistical hurdle to set up while Congress, think tanks and Army Secretary Christine Wormuth raised concerns on the test’s impact on women. And despite finally putting the test into effect, more changes are likely coming, though they are expected to be minor.

“This is probably the most studied, talked-about, reviewed and scrutinized fitness test, probably in the history of the world. Certainly more than our sister countries and services,” Michael McGurk, who oversaw the development for the ACFT, told Military.com.

Meanwhile, Sergeant Major of the Army Michael Grinston was constantly traveling between bases beating the drum as the test’s hype man, selling a skeptical rank and file on what will be one of the most important new elements of their careers.

Active-duty soldiers take fitness tests for record twice a year while part-time troops in the reserve components take them once a year. Those scores can largely dictate their careers, playing a big role in promotions, especially in combat arms. Failing to pass can lead to being removed from the service.

For Grinston, with a year left as the service’s top enlisted leader, he sees getting the test across the finish line as one of the proudest moments of his career.

“We’ve had three failed attempts to get the Army to change the PT test, but we did it,” he told Miltiary.com in August. “It’s gonna make us more lethal.”

Military.com interviewed dozens of soldiers across all ranks over the past year about the new fitness test. Many had opinions on how the test can or should be tweaked. Some soldiers, especially in the Reserve and National Guard, are irritated over the heavy reliance on specialized gear and the difficulty that presents for training in civilian gyms. Some think the minimum standards are far too low while others question the purpose of a fitness test altogether.

All sources interviewed with direct knowledge of the ACFT’s development underlined just how difficult it was to launch a new fitness test in an Army that’s slow to change.

Army officials have tried several times since the 1980s, but such efforts quickly crashed and burned. Yet the smoke has mostly cleared. The closer the Army got to the test going live on Oct. 1, the less soldiers voice objections in interviews. A lot have generally accepted the ACFT as a much-needed improvement over its predecessor and is broadly seen as easier to pass but much more difficult to earn a perfect score. In many cases among junior troops, it’s the only test they know. But most are simply tired of the debate over scoring and which exercises should end up in the final package.

Some even think it’s fun.

“It [is] much more of a social event,” one noncommissioned officer told Military.com, comparing it to the previous fitness test. “It builds camaraderie. It is much less violent on your body. No more desperate thrashing of your hip flexors before a two-mile run. Frankly, I think it’s the best new thing the Army ever implemented.”

How It Started

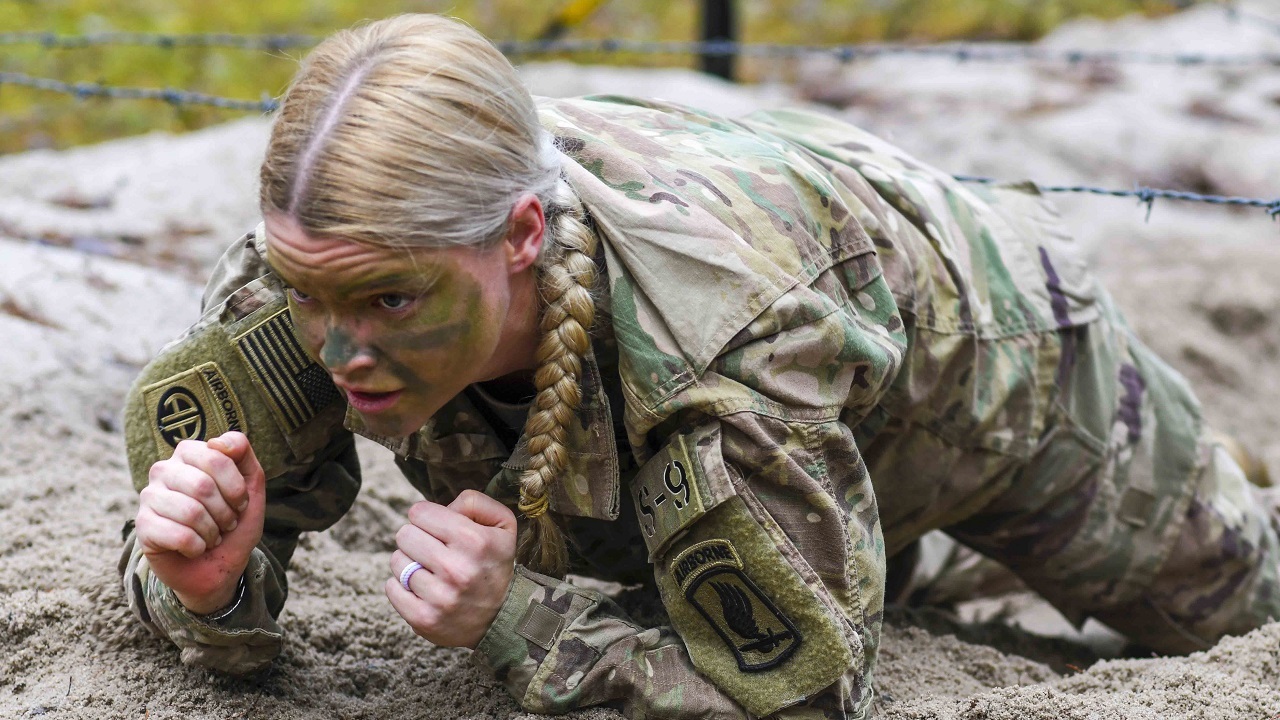

The ACFT is a six-event test including deadlifts, hand-release push-ups, a plank, a two-mile run, an event which soldiers must yeet a 10-pound medicine ball as far as they can, and another event consisting of carrying 40-pound kettlebells, dragging a 90-pound sled and sprinting.

It’s a far more complicated event than its predecessor, the Army Physical Fitness Test, or APFT, that the service has used since 1980. That was only a three-event test measuring push-ups, sit-ups and a timed two-mile run. The APFT was largely seen as too simple, possibly an overcorrection from other prior fitness tests that sometimes used ladders, obstacle courses and other logistically burdensome requirements.

President Theodore Roosevelt is largely credited with establishing graded fitness tests, implementing one consisting of a 50-mile walk within 20 hours, a 90-mile horseback ride in three days or a 100-mile bicycle ride to be completed within three days.

After nearly a decade into the Global War on Terrorism, it became clear to Army leaders that the service needed new fitness standards, especially after multiple major deployments to the mountains of Afghanistan.

“I had a young captain who influenced me a lot in terms of thinking who spent seven months in the Korengal Valley [Afghanistan], and we talked a lot about taking direct fire every single day, every time he stepped out of the chopper or wherever he was,” Whitfield East, an Army physiologist who helped develop the ACFT, told Military.com. “It was a rigorous environment.”

The first major meeting on replacing the APFT was in October 2010 with Lt. Gen. Mark Hertling, who oversaw the Army’s Center for Initial Military Training, or CIMT. Hertling, who has since retired, is seen as one of the main driving forces to getting a new fitness test off the ground. Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was also a huge advocate for a new fitness test behind the scenes, according to multiple sources.

Researchers looked into a huge roster of exercises, including pull-ups, dips, deadlifts to fatigue, medicine-ball rotation workouts, crunches, sit-ups, a 400-meter sprint and a vertical jump. They even mulled allowing soldiers to fail one or two events on the test but still pass overall.

Eventually, in 2016, the name ACFT was coined.

“We first started calling it the Army Physical Readiness Test; we got about halfway through the study and got pushback from some folks about readiness because it was such a broad term,” East said. “We were always going to have [the word] ‘Army’ in it. We were always going to have ‘fitness’ and we were always going to have ‘test’ in it. So that makes the fourth letter pretty easy.”

The two major goals behind developing the ACFT were to mitigate injuries and to diversify the Army’s workout routine, that until now, was largely centered around running and push-ups. Not all Army bases are equipped with state-of-the-art gyms, but some of the newer ones have all the accoutrements of a high-end CrossFit gym with rows of squat racks, plyo boxes, battle ropes, assault bikes and plenty of space to deadlift.

Yet the gear-heavy test drew the ire of some in the National Guard and Reserve. Civilian gyms rarely have enough space to throw a medicine ball or all the gear and space required to practice the Sprint-Drag-Carry event. Army officials have put out a series of workout options that do not require special equipment, though it’s unclear how successful a soldier can be on the test sticking to those alternate training programs.

But a gear-heavy test wasn’t part of the plan initially. At first, officials wanted a test that could be conducted anywhere at any time, which was one of the redeeming qualities of the old APFT. But relying on body-weight fitness options alone, they could only come up with a test that was marginally better than what was already the Army standard. Given the difficulty of fundamentally changing how the Army conducts physical fitness, the bang wasn’t worth the buck. The service, they concluded, had to use some gear.

“We then thought if we were going to design a new PT test, we need to use equipment, but we minimize the amount of equipment we use,” McGurk said. “[We wanted] to keep it as simple as possible … and, relatively speaking, portable. It’s not something you can stick in your pocket, but you can certainly set it up in a location, break it down and move it all somewhere else if needed.”

That gear ended up including kettlebells, bumper plates, sleds and a hex bar, all of which are relatively portable — a strict requirement from service leaders as it became quickly apparent that integrating any sort of obstacle courses, ropes or ladders wasn’t feasible for most units. The service spent $70 million just on the initial contract with Sorinex, which was likely the largest single purchase of exercise equipment, in the military’s history, but has also bought gear from Rally Fitness and Rogue.

Bout with Congress

The most difficult part of developing the test was figuring out how it should be scored. Army planners initially aimed for a gender-neutral test that would grade soldiers based on their job, the idea being an infantryman needed to carry more weight and run faster than a chaplain. That’s when the test hit turbulence. Gen. James McConville, the Army’s chief of staff, told lawmakers in June 2021 that he was committed to having the test grade men and women the same.

The Army started testing those standards in 2019 and smashed right into the coronavirus pandemic, effectively torpedoing the ACFT’s development and delaying its final rollout. Then, the test drew scrutiny from Capitol Hill, specifically Sens. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., and Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., who were able to delay the test further in the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, passing a requirement into law that implementation would remain on hold until a third-party study examined the test’s impact on recruiting and retention — specifically with women.

Concerns about the test were compounded when Army Secretary Christine Wormuth expressed skepticism about the ACFT during her confirmation hearing in May 2021.

“I have concerns on the implications of the test for our ability to continue to retain women,” Wormuth told lawmakers, adding that she was also concerned over how strict fitness standards will impact high-demand jobs that are typically far from the frontlines, including cyberwarfare.

Three days before that hearing, Military.com reported on early Army data showing nearly half of the women in the service were failing the test while men breezed through it and the few women who did pass performed well.

The study mandated by Congress was conducted by Rand Corp. and publicly released in March of this year. It included damning findings on how women were performing, echoing Military.com’s earlier reporting on initial test data.

Rand’s report also killed one exercise, the leg tuck, which wasn’t found to appropriately measure core strength. The plank took its place.

Those findings were the nail in the coffin for a gender neutral test. The Army faced an unwinnable public perception issue: Keep the standards as-is and risk having to boot women en masse, or change the grading, reversing a major justification for creating a new test and taking heat for the perception of lowering the standards.

The Army reverted back to an APFT-style grading system, assessing soldiers based on gender and age, which irked several commanders behind the scenes. Army leaders changed the idea that the test measures a soldier’s ability to perform in combat to it being a “general fitness test.”

“There should be one standard for combat arms branches and it shouldn’t be gender based,” one female artillery officer told Military.com. “The soldiers in my platoon all have to carry artillery rounds. [High-explosive] 155mm rounds are loosely around 100lbs, that weight doesn’t change based on the gender of the person carrying it. I need my soldiers to be able to carry a lot of these rounds, not just one round and then they’re done.”

That same month, lawmakers on the House Armed Services Committee passed an amendment into the annual defense policy bill directing the Army to establish new fitness standards for combat arms troops. It was a move that some see as a compromise between the early idea on how to grade the test while also not requiring too much of soldiers in jobs that aren’t physically demanding, something the Army was already working on, one source with direct knowledge told Military.com.

“If we stumbled anywhere, it was perhaps going too far, too fast,” East said. This [test] will have to go back into a cycle of revisions and updates.”

Steve Beynon is a reporter for Military.com (where this first appeared) based in Washington D.C. He specializes in covering ground combat. An Afghanistan war veteran, serving over a decade as a cavalry scout, he currently serves as a non-commissioned officer in the National Guard. He previously covered Capitol Hill and the Department of Veterans Affairs for Stars and Stripes. His work has also appeared in Politico, The Washington Examiner, National Guard Magazine and Military Times. In his hometown of Cincinnati, Steve wrote for the Cincinnati Enquirer and worked at Fox 19.