Nuclear weapons nonproliferation is one of the most sacred totems in U.S. foreign policy. America’s commitment to preventing even its closest democratic allies from acquiring nuclear weapons has left Washington with a gaggle of dangerous nuclear commitments around the world. In principle, if, say, Montenegro is threatened militarily, the U.S. is committed to using nuclear weapons for the country’s defense, even if the result would be America’s destruction.

This policy is reckless and foolish.

Indeed, Washington finds itself in an increasingly hot proxy war with nuclear-armed Russia, with U.S. officials attempting to discern Moscow’s potential red lines. At what point might ill-disguised American involvement in the conflict, combined with Russian conventional weakness, push the Putin government to use tactical nuclear weapons to retrieve its battlefield position? Could Washington be pulled into a cycle of mutual escalation?

In Ukraine’s Defense: Time for Nuclear Weapons?

The Ukraine conflict might have been entirely avoided had the U.S. not pressured Kyiv to yield the nuclear weapons left in its possession when the Soviet Union collapsed. When 1992 dawned, Ukraine was theoretically the world’s third-largest nuclear power with some 1,900 strategic and 3,000 tactical nuclear warheads, as well as 176 intercontinental ballistic missiles and 44 strategic bombers. However, in December 1994 Kyiv agreed to yield its nuclear weapons in a pact known as the Budapest Memorandum. Alas, the agreement offered Ukraine no security guarantees—adherents to the 1994 Budapest Memorandum merely promised to take any attack on Ukraine to the United Nations Security Council, on which the most likely aggressor, Russia, possessed a veto.

Nevertheless, at the time abandoning its nukes seemed like the right decision for Kyiv. Ukraine was unstable politically and bereft economically. It depended on the largesse of the West and the goodwill of Moscow, both of which would have been at risk had Kyiv not agreed to go nuclear-free. Aggression by Russia seemed unlikely. Moreover, Ukraine lacked the weapons’ operational codes, though the nuclear material could have been reused. Reconstituting and maintaining a nuclear force would have been a major burden.

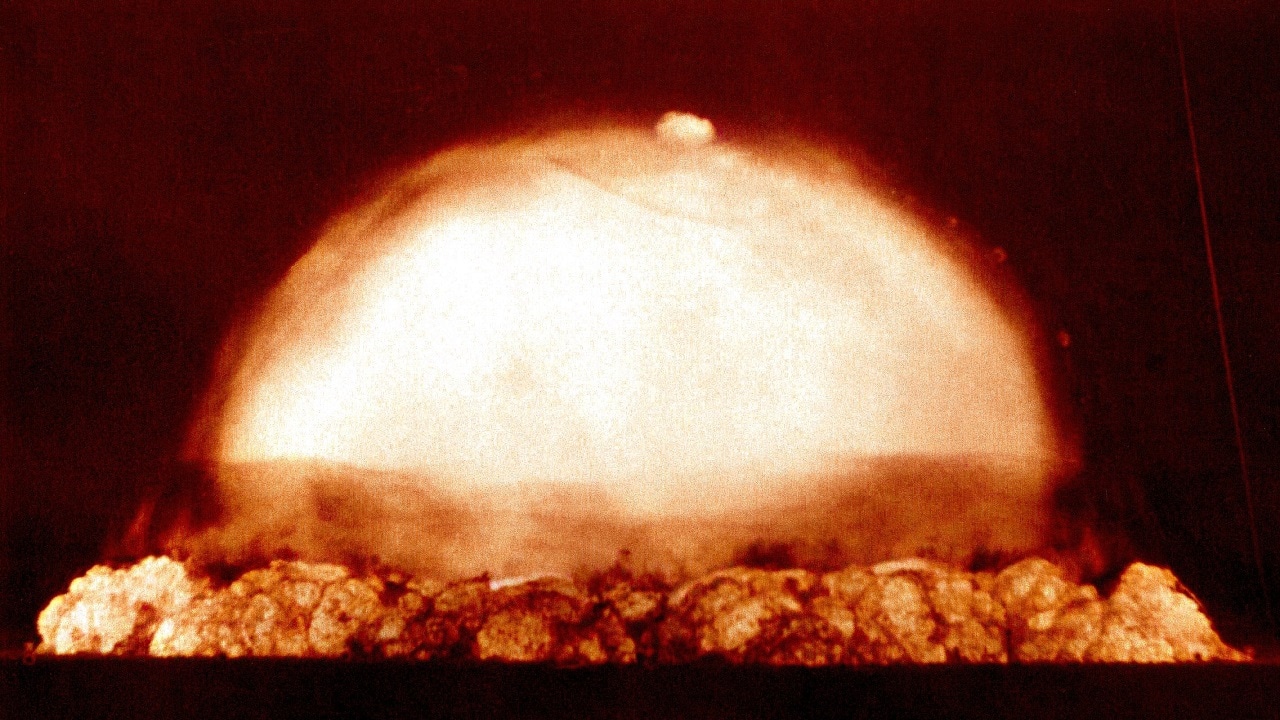

And yet, imagine if Kyiv had possessed even a small nuclear deterrent on February 24, 2022. It is unlikely that Russia would have attacked. The risk of retaliatory destruction would have been too great. A similar fear, instilled by America’s nuclear arsenal, helped ensure that the Red Army never tested Western Europe’s ability to withstand an attempted Soviet Blitzkrieg.

Now the issue recurs. The Zelensky government wants security guarantees, preferably NATO membership, as part of any agreement to end the conflict. That won’t come easy. Although in 2008 at Washington’s insistence the allies committed to incorporating Ukraine (and Georgia), they spent the following 14 years running from their promise since no one wanted to risk war with Russia. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin continued to offer what amounted to polite falsehoods when visiting Kyiv just a couple of months before Russia’s invasion. And even with Ukraine under attack, the allies refused to enter the war directly.

So how will Ukraine be defended, assuming the war ends without a Russian collapse, which doesn’t look likely?

Taiwan Poses a Parallel Conundrum

A similar issue is bedeviling U.S. policy toward Taiwan. The main island is barely 100 miles off China’s coast and thus vulnerable to attack. Although the Carter Administration abrogated America’s mutual defense treaty with the longstanding Republic of China when recognizing the People’s Republic of China, Washington continued to maintain an ambiguous defense commitment to Taipei. Doing so seemed easy during the early years since the PRC lacked the military means to threaten Taiwan seriously.

Even when China brandished missiles in advance of the reelection of ROC President Lee Teng-hui during the 1995-96 Taiwan Strait crisis, the threat was modest. The Clinton administration responded by sending two aircraft carriers and accompanying ships to the region as a show of force, against which Beijing had no recourse. The result was humiliating impotence for Beijing, creating a powerful incentive for the PRC’s ensuing military buildup.

Today the Chinese military is much more capable. The consensus in Washington is that the U.S. should still defend Taiwan, but how remains unclear, given the latter’s distance and lack of certain allied support. Some policymakers imagine verbal threats deterring PRC intervention, which vastly underestimates the intensity of China’s commitment to reunification. The main debate in Washington appears to be over whether the U.S. should move from “strategic ambiguity” to “strategic clarity,” making America’s commitment explicit.

Yet the U.S. could lose such a conflict. Its forces would lack air superiority over the island, be dependent on access to allied bases, and face enormous losses if operating near the coast of China. In wargames, China has most often triumphed. The less frequent U.S. victories have been dearly bought. The Center for Strategic and International Studies recently completed a series of tests, reporting success in saving Taiwan but warning that “this defense came at high cost. The United States and its allies lost dozens of ships, hundreds of aircraft, and tens of thousands of service members. Taiwan saw its economy devastated. Further, the high losses damaged the U.S. global position for many years.”

Particularly fearsome is the prospect of escalation. Taiwan is an existential issue for Beijing, which the former cannot afford to lose. The PRC would rely on mainland bases, ensuring American attacks on such facilities, which in turn would trigger retaliation against U.S. territory. If neither Beijing nor Washington was prepared to yield, escalation would be difficult to halt, short of the use of nuclear weapons. The prospect of moving down this path would force any president to hesitate, and perhaps pull back and decide not to get involved, despite Washington’s long, ambiguous commitment to do so.

So how should Taiwan be defended, whether or not the U.S. is prepared to act?

Korea Has its Adversary

That’s not all. The Republic of Korea is another long-time security dependent, despite possessing some 50 times the economic strength and twice the population of the North. Once reliant on American defense welfare, always reliant on American defense welfare, it seems. At least, similar to the case of Taiwan, American “extended deterrence” was relatively costless when the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea only had conventional arms, meaning a capable army. Any U.S. casualties would be limited to the Korean peninsula and Washington could use its entire arsenal in response to a North Korean attack. This situation is no longer the case, however.

The DPRK has been rapidly building up its nuclear arsenal and missile inventory, with Kim calling for an “exponential” increase in nuclear weapons. The Rand Corporation and Asan Institute warned: “by 2027, North Korea could have 200 nuclear weapons and several dozen intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and hundreds of theater missiles for delivering the nuclear weapons. The ROK and the United States are not prepared, and do not plan to be prepared, to deal with the coercive and warfighting leverage that these weapons would give North Korea.”

Facing such a force, which could target American cities, would an American president be willing to defend South Korea? By all evidence, Pyongyang is a rational actor and wouldn’t launch a suicidal first strike on America. However, even what begins as a conventional conflict could go nuclear, since the North might respond to the possibility of regime change by the U.S. with a threat to attack America’s homeland. Imagine an allied defeat of North Korean conventional forces and an allied plan to march north, ala late 1950, followed by a demand from the DPRK that American and South Korean forces desist or face nuclear annihilation. Imagine such an ultimatum backed by a demonstration nuclear explosion on the outskirts of Seoul.

Nuclear Weapons and Keeping the Peace

In all these cases possession of nuclear weapons would benefit America’s clients, giving them control over their own security. Only then would they enjoy some certainty. For instance, Ukraine might have to wait a long time, and perhaps forever, for either the U.S. or Europe to offer to fight on Kyiv’s behalf. An ambiguous American commitment to defend Taiwan might be better than nothing for Taipei. Still, there is no certainty that a future U.S. president would risk America’s survival on Taiwan’s behalf.

In contrast, South Korea enjoys a treaty commitment. However, paper guarantees look increasingly fraught as the DPRK continues to expand the size and accuracy of its nuclear and missile arsenals. Moreover, though war over Taiwan would not directly threaten the survival of the Chinese regime; a conflict on the Korean peninsula would put Pyongyang’s existence in doubt. Would future U.S. administrations forever risk everything for the ROK?

Ukraine has no easy path back to nuclear status, but Taiwan once had a nuclear program and could resume its effort, as some analysts suggest. Even more so in Seoul, as ROK actively sought nuclear weapons a half-century or so ago. And there is substantial public support for the acquisition of nuclear weapons today, with President Yoon Suk-yeol recently mooting the possibility.

The consequences of even friendly proliferation would be serious, of course, but U.S. security should come first. Risking the American homeland on behalf of anything short of an existential threat—an attack on the U.S. itself—is not just foolish, but also a betrayal of Washington’s responsibility to its own people. Moreover, the promise to risk destruction on behalf of other nations is becoming less believable.

MORE: Ukraine Needs M1 Abrams Tanks Now (But Will Have to Wait)

MORE: Joe Biden Won’t Send F-16 Fighters to Ukraine

MORE: Why Putin Should Fear the F-16 Fighter

MORE: Why Donald Trump Can’t Win in 2024

Noted Foreign Policy’s Stephen Walt: “convincing people you might use nuclear weapons to defend an ally isn’t easy.” With the potential of American involvement in hot conflicts involving Russia, China, and North Korea, possibly simultaneously, the U.S. should rethink its commitments, especially to fight nuclear wars for other nations.

There are obvious downsides to proliferation, but only the second-best security solutions are available today. Instead of arbitrarily ruling out what might be the most realistic option, the relative costs and benefits of friendly proliferation and extended deterrence should be compared and debated. And the interests of the American people should be emphasized. For they are who Washington’s foreign policy elites are supposed to serve.

Doug Bandow is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. A former Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan, he is author of Foreign Follies: America’s New Global Empire.