Just after 4 a.m. on Feb. 6, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck Gaziantep, in southeastern Turkey. Nine hours later and about 60 miles north, another major earthquake (7.5 magnitude) struck Kahramanmaraş.

The combined effects of two major earthquakes just hours apart destroyed entire villages, towns, and districts. The quakes toppled nearly 200,000 buildings across 10 Turkish provinces. They killed more than 50,000 people and injured more than another 170,000 in Turkey and Syria, casualty figures that sadly are very likely significant undercounts and indeed continue to grow. Since Feb. 6, four additional earthquakes of magnitudes 5 or higher as well as 45 aftershocks have rattled the region, adding to the death and destruction.

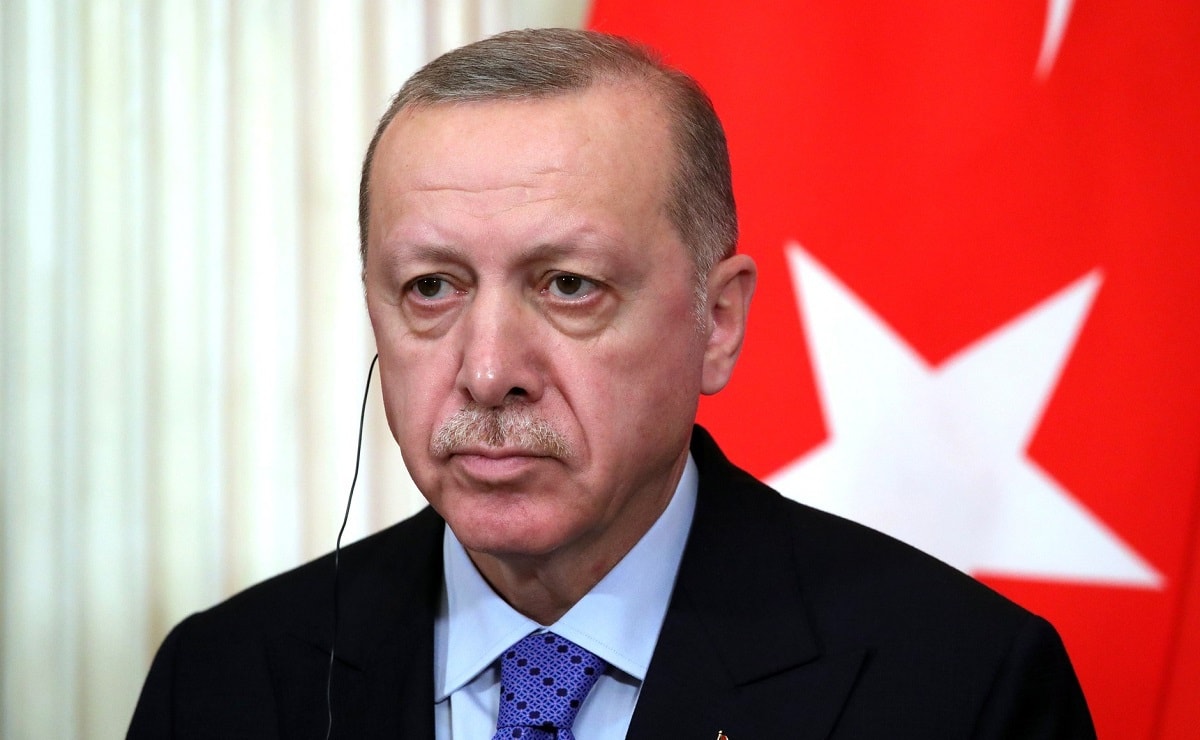

Turkey is unfortunately no stranger to earthquakes, with the last major earthquake killing more than 17,000 in western Turkey in 1999. Compounding the humanitarian crisis caused by the earthquakes, the Turkish government’s preparation for the event was clearly inadequate, and its initial response was slow and insufficient, causing widespread anger. Allegations of shoddy construction, and of corruption in the waivers granted from earthquake building codes put in place after the 1999 earthquake, have exacerbated public animosity towards Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The president has ruled Turkey since 2003 and came to power himself in part due to the political aftershocks of the 1999 earthquake.

Anger Bursts Forth in Turkey

There is good reason for the criticism directed at the government. After the 1999 earthquake, the Turkish military immediately responded — it deployed tens of thousands of troops within 48 hours. This time, however, the Turkish military deployed only 9,000 troops in the two days after Feb. 6, limited in part by reforms in 2016 that placed the military under greater civilian control. (This was an arguably logical decision, coming as it did after the failed July 2016 military coup attempt.) The changes removed the Turkish General Staff’s authority to respond immediately to natural disasters.

The Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency’s response to the earthquakes was also slow and underwhelming, with much of the initial search and rescue efforts conducted by residents of the disaster zones. Accounts abound of trapped earthquake survivors living for days beneath the rubble, but many more probably died because the Turkish government’s response was so poor.

All of this has generated widespread anger, as grieving Turks have begun to ask why the earthquakes caused so much death and destruction. To be fair, any single earthquake of the same magnitude would cause substantial death and damage if it occurred in any given populated area, including, for example, along the San Andreas Fault in California. Two earthquakes of this magnitude striking in such close geographic and temporal proximity is unprecedented, and few, if any, models assess such a potential. And although Erdoğan has amassed great power in Turkey over the last two decades, he does not have any influence on the occurrence of natural disasters. He certainly does, however, have immense influence in and control over the Turkish government’s response. This response — slow and insufficient as discussed above — appears to have been compounded by corruption. Specifically, the alleged corruption concerns ties between Erdoğan’s party and government on one side, and construction firms for which earthquake building codes were reportedly waived on the other. These firms, freed from constraints enacted in 1999, allegedly went on to construct unsafe buildings. Popular anger, then, seems very much warranted, even if enforcement of building codes in earthquake zones is notoriously difficult.

Plenty of Precedent

Prominent Turkey experts have assessed these developments and declared the country is entering into “terra incognita” — earthquakes and the public anger they set loose have upended Turkish politics, much as the earthquakes themselves reshaped Turkey’s geography. The general argument is that the outcome of the elections announced for May in Turkey, should they occur, might finally oust Erdoğan from power.

Yet there are important ways in which the circumstances in Turkey are hardly unprecedented. Indeed, natural disasters have occurred throughout human history, and many studies have assessed the impact natural disasters have on elections. Despite this academic abundance, analysis of how the earthquakes might impact Turkey’s May elections often fails to take the vast literature on this topic into account. And while the various studies have produced decidedly mixed results that depend on a range of factors, the general trend is that while voters tend to punish incumbents for natural disasters, voters also tend to reward incumbents for disaster response, perhaps because government spending tends to increase after a natural disaster. Often, disaster relief can actually improve electoral prospects.

This suggests that voters may punish Erdoğan both for the earthquakes themselves and the Turkish government’s lackluster initial response. However, there are still just over three months until the Turkish elections on May 14, giving Erdoğan and the Turkish government a good deal of time to provide the sort of post-disaster aid associated with the improved electoral support that the literature identifies.

Erdoğan and his government may have failed in the initial earthquake response, but the Turkish rebuilding effort is already underway. It is accompanied by updated building regulations and a pledge by Erdoğan to provide new homes within a year for all Turks left homeless by the earthquakes. Notwithstanding issues related to earthquake building codes, Turkish construction firms have a track record of quickly completing quality projects, and they are likely up to the task. Furthermore, Turkey has received a large amount of aid, including an initial tranche of $1.78 billion from the World Bank, $185 million from the U.S., $100 million from the UAE, and more than $300 million from a range of countries including Germany, Kuwait, the UK, Canada, and many others. Meanwhile, a domestic fundraising call-in show on Feb. 17 generated more than $6 billion in aid for earthquake victims, including more than $1 billion donated by the Turkish Central Bank. Major Turkish banks and companies are also donating hundreds of millions of dollars each.

While these initial donations only start to chip away at the damage caused by the earthquakes, which is estimated at $84 billion, they do provide additional resources with which Erdoğan may achieve the level of emergency relief that will lead voters to reward his efforts. How successful Erdoğan’s earthquake recovery efforts are over the next several months will probably have a major impact on election results in May.

Possible Measures

Erdoğan’s own political success over the last two decades offers additional insight into what may lay ahead. Since 2002, Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party have won national elections with varying vote shares, ranging from 34% in 2002 to 52.5% in 2018, and higher margins in local elections and referendums.

Erdoğan’s electoral history very much suggests he will do everything possible to win the upcoming election. The idea of postponing the election was floated publicly by Erdoğan allies in the days immediately following the earthquakes, a common tactic used to gauge public responses. More recently, government sources have said the election is likely to go forward in June, as originally scheduled, not a month earlier as Erdoğan had announced in January 2023.

If the election is held in May or June, observers should be on the look-out for irregularities, including things like large increases in registered voters, questionable data on invalid votes, and odd vote share increases, as well as potential cancellation of results not supportive of Erdoğan or his party (although such shenanigans backfired spectacularly the last time Erdoğan took such a step). Erdoğan already used a national referendum in 2017 to significantly amend the Turkish Constitution. The changes increased his power considerably and established a precedent suggesting he will show little restraint in shaping events to support his desired outcomes.

Well-informed observers have argued that delaying the election would be unconstitutional, apparently assuming that should Erdoğan desire a delay, unconstitutionality would be unlikely to stop him, and omitting the possibility that Erdoğan could force an emergency constitutional or electoral rule change. In other words, Erdoğan over the last several decades has provided plenty of examples to show what he is willing to do to stay in power. Additionally, the studies on elections and natural disasters discussed above also suggest that postponing elections is well within the normal range of responses to major incidents, as are changes to electoral processes, campaign rules, and cancellations.

In sum, Turkey is not entering into unknown territory as many analysts have insisted. Rather, both Erdoğan’s own political career and the long history of how natural disasters have impacted elections help show us what might transpire in Turkey over the coming months.

Still, the Turkish government’s wholly insufficient initial response to the Feb. 6 earthquakes should be a cause of concern for Erdoğan. It will likely reduce or complicate his chances of re-election. Pre-earthquake polling in January 2023 showed support for Erdoğan’s coalition with the far-right Nationalist Movement Party standing at 42% on average, followed closely by the main opposition coalition at 39%. As it stands right now, post-earthquake polling suggests support for Erdoğan’s coalition has dropped to 35%, while support for the opposition has risen to nearly 48%, clearly sending warning signals to Erdoğan. If elections do occur in May or June, though, Turkish voters might no longer be in a mood to punish Erdoğan for the earthquakes or the failed initial response.

Jeff Jager holds a B.S. from the U.S. Military Academy; an A.A. in Turkish from the Defense Language Institute; and three M.A.s (Turkish Army War College, security studies; Georgetown University, German and European studies; Webster University, international relations). He is currently a Ph.D. student in Salve Regina University’s international relations program.