Ukraine dominates the news because it happens in full view of the world. China’s destruction of Uyghur lands is far more systematic but occurs in the dark.

The international community can ignore it or simply virtue signal with meaningless rhetoric but take no action because China’s draconian controls keep Uyghur suffering out of the daily news cycle.

It is for this reason that Gulchehra Hoja’s new book, A Stone is Most Precious Where it Belongs, is so valuable. Hoja is an accomplished journalist. She left Xinjiang television after refusing to promote the Chinese Communist Party propaganda and found a home at the U.S.-funded Radio Free Asia, the only Uyghur broadcaster that allows an independent line. That move earned her a red notice and a ban on returning to China. She is both an excellent writer and a scholar and approaches the Uyghur genocide with a depth many journalistic accounts lack.

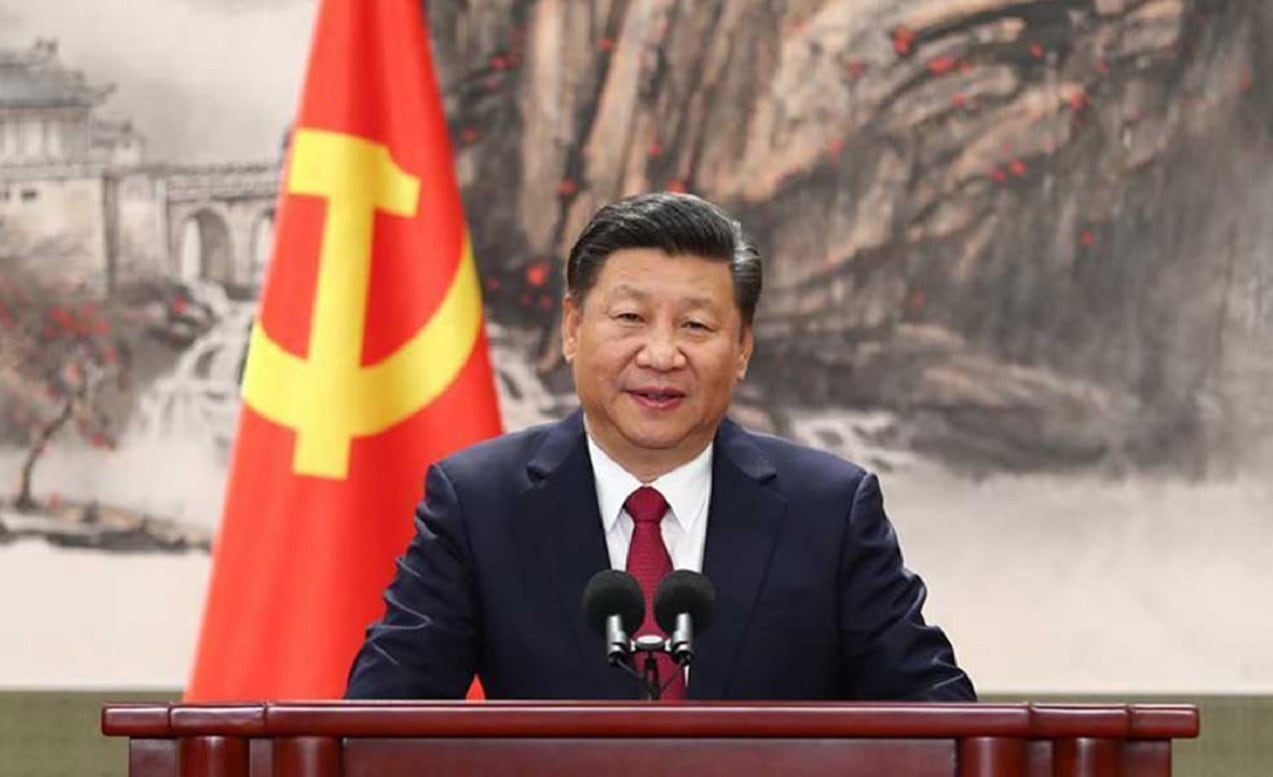

It is for this reason that Chinese President Xi Jinping will hate Hoja’s work, because it is not something that Chinese Communist Party-sponsored junkets for foreign reporters and religious organizations can refute.

Just as Chinese authorities craft an artificial narrative to suggest Taiwan to be part of China, Hoja shows how they crafted a big lie to lay claim to East Turkestan. “Up until 1949, East Turkestan proudly waved its own flag, and came as much within the cultural sphere of the Soviet Union as of the Chinese state,” she explains. “Although it was a majority Uyghur area, with Uyghurs constituting 75 percent of the population until the mid-twentieth century, there was also a sizable population of Kazakhs, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Tatars, and Kirgiz, most of whom follow some form of Islam. It was a delicate balance, one that in the mid-1900s the Chinese government began to systematically destroy.” The name Xinjiang, she teaches, Chinese for “new territory” is just a recent creation.

The victory of Mao Zedong was a death knell for Uyghur self-determination. While Hollywood brought the story of Tibet’s conquest to the big screen, and A-list actors made Tibet’s cause their own, East Turkestan got no such exposure. The Uyghur’s experiences were similar, however. Mao settled Han Chinese in the northern part of East Turkestan. “Simply put, the situation became one of a colonized people and a colonial overlord, with all the shots called by the communist powers in Beijing,” Hoja explains. Within just a few decades, Uyghurs were a minority in their own land.

The Tibet and Uyghur experience diverged in 2017, when Chinese authorities transferred huge numbers of Uyghurs into detention camps built in the middle of the desert. “Somewhere between one million and three million people have been forced into these camps, where they’re subjected to dehumanizing treatment, such as torture, rape, forced labor, and routine,” she estimates. Even those not yet sent to camps are under constant surveillance. “High-tech cameras hang on every telephone pole and can identify Uyghur individuals using sophisticated facial recognition software developed specifically for the purpose of keeping the population intimidated and in line,” she explains. “On corners where watermelon vendors used to park their donkey carts or trucks, military police now stand with machine guns at the ready. Policemen march in formation everywhere, and even going to buy vegetables at a bazaar requires an invasive search. A Uyghur needs an ID even to buy gas at a gas station,” Hoja writes. Han Chinese face no such restrictions.

What makes A Stone is Most Precious Where it Belongs so compelling, however, is how Hoja not only explains the current terror, but she juxtaposes it with what came before. She describes growing up in Ürümchi, and playing in former U.S. consulate, abandoned by the State Department in 1949 when American diplomats fled in the face of Mao’s victory. She describes an idyllic girlhood punctured by growing cultural assaults by Han migrants. Mahallas—neighborhood communities—did not translate when Chinese bulldozers destroyed old towns in order to construct new high rises. Community dissipated.

So too did family units as Mao’s Cultural Revolution purposely broke down anything that could compete with party. “Uyghurs felt that the upheaval had to do with the Han and their culture, and that it shouldn’t involve the Uyghurs at all. But the political forces were too strong to avoid,” she relates; the repression touched her own family, as the communist regime forcibly separated her parents for a time.

They were relatively lucky; her great-grandfather had been executed years earlier in revenge for advocating for Uyghur independence. She describes school, learning Chinese, discovering her own family history, and her first experience as the victim of corruption, being denied a scholarship after another student’s family paid a bribe. She describes life at the university, college students’ social lives, and the clash between Uyghur and Chinese expectation.

This clash grew as Hoja became involved, first in movie making and then television. The Chinese Communist regime also became more overbearing. Police arrested—and then tortured—her brother on trumped up charges, ultimately sentencing him to a decade in prison. Authorities forced her mother to end pregnancies to conform to China’s one-child policy.

Hoja’s entire story is worth reading on a number of levels. It is an education into Uyghur culture and history. It humanizes tragedy millions of her compatriots face today. Perhaps its greatest importance is exposing the moral and intellectual bankruptcy of China today. Indeed, Hoja’s intellectual sparing and subtle resistance to Chinese communist functionaries transforms A Stone is Most Precious Where it Belongs into a Uyghur equivalent of Fear No Evil, the prison memoir of Natan Sharansky as the Soviet Union’s most famous dissident resisted his KGB tormentors.

As the Uyghur holocaust continues, A Stone is Most Precious Where it Belongs should be required reading not only for any U.S. diplomat or official working on China but, indeed, for every U.S. diplomat, congressional aide, and flag officer, not only for what it teaches about the Uyghurs but, as importantly, for how it demonstrates the moral and intellectual bankruptcy of America’s most powerful competitor today.

Author Expertise and Experience

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, Dr. Michael Rubin is a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). Dr. Rubin is the author, coauthor, and coeditor of several books exploring diplomacy, Iranian history, Arab culture, Kurdish studies, and Shi’ite politics, including “Seven Pillars: What Really Causes Instability in the Middle East?” (AEI Press, 2019); “Kurdistan Rising” (AEI Press, 2016); “Dancing with the Devil: The Perils of Engaging Rogue Regimes” (Encounter Books, 2014); and “Eternal Iran: Continuity and Chaos” (Palgrave, 2005). The ideas expressed in this piece are the author’s own.