What the AUKUS submarine deal could mean: On Monday, leaders of the U.S., Australia, and the UK including President Joe Biden, Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese, and British prime minister Rishi Sunak, are meeting in San Diego to unveil a plan that will see the ‘land down under’ acquire its first-ever nuclear-powered submarines by the early 2030s—used ones, reportedly, initially crewed in large part by American sailors. The acquisitions would be followed in the 2040s by Australian-built boats based on a British design.

Specifics of the AUKUS plan, first reported by Reuters and subsequently elaborated by other sources, look ambitious, expensive, and full of political risks.

AUKUS Politics

The submarine pact is clearly intended to enhance the AUKUS members’ capability to counter China’s military expansion into the Pacific. This wasn’t lost on Beijing, which issued a statement last week claiming the deal “hurts peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific” and poses a nuclear non-proliferation risk.

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) currently operates six aging Collins-class diesel electric attack submarines needful of replacement in the 2030s. In 2021, Australia caused a stir when it canceled a $66 billion deal to procure French-built submarines even as it revealed alternative plans to acquire pricier nuclear-powered submarines via a pact with the United States and United Kingdom called AUKUS.

The new plan already seems a tricky needle to thread, as both British and American submarine builders are overbooked and Australia has limited experience with nuclear technology.

Initial Acquisition Plans

Canberra’s current objective is to acquire eight nuclear-powered attack submarines, or SSNs—and the capacity to build them domestically. The Australian-built sub will likely be based on the UK’s next-generation SSN(R) attack submarine program due in the 2040s, including its Rolls-Royce PWR3 reactor. Australia’s version, however, will be equipped with U.S. weapons and BYG-1 combat systems (already used on RAN submarines).

But prior to that, the plan is for the U.S. to sell three, with the option for up to five, of its Virginia-class attack submarines in U.S. Navy service in the 2030s.

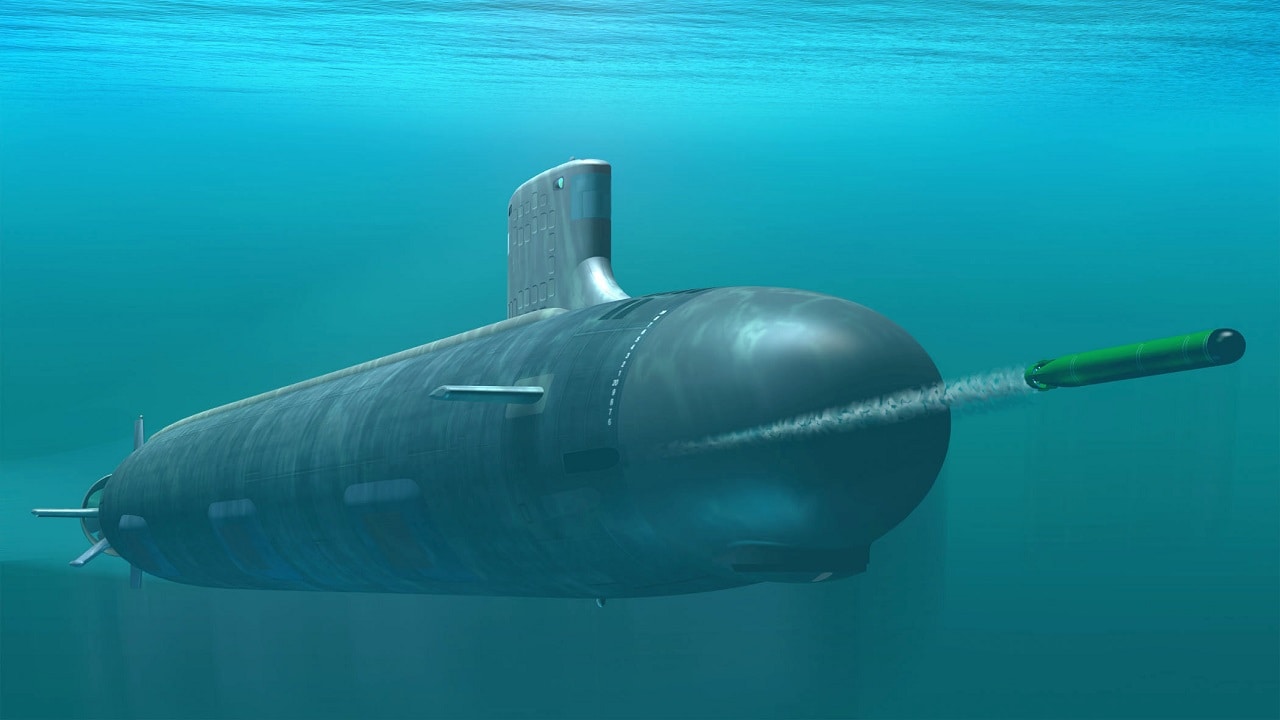

Virginia-Class Submarines

The Virginias, which have a standard crew of 132, are arguably best-in-class due to U.S. advancements in acoustic stealth, including quieter high-speed cruising. By early 2023, there are 21 in service, gradually replacing aging-out Los Angeles class submarines, and serving alongside three larger, premium Sea Wolf-class boats. In December 2022, the first of the Block V Virginias was laid down, sporting additional vertical launch systems increasing capacity from 12 to 40 Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles. These subs will also eventually support hypersonic weapons.

Initial groundwork for the Virginia handover would begin in 2023 with annual visits by U.S. submarines to Australian ports. Meanwhile, Australian workers would travel to the United States to learn production techniques, and incidentally help fill a labor shortage in America’s submarine-building industry, with Grotton, CT-based Electric Boat by itself reportedly seeking 5,000 new hires. Canberra may also contribute up to $1 billion to expand the U.S.’s strained submarine industrial base.

New Mexico is the sixth ship of the Virginia class. With improved stealth, sophisticated surveillance capabilities and special warfare enhancements, it will provide undersea supremacy well into the 21st century. (Photo by Chris Oxley)

By 2027, a forward deployed base for U.S. submarines would be activated in Western Australia, capable of servicing and sustaining operations for U.S. (and eventually Australian) SSNs. Locally stationed subs would operate with mixed U.S. and Australian crews.

Then, according to Australia’s Financial Review, in the 2030s, Canberra would select at least three—but optionally up to five—of the jointly crewed Virginias for purchase at a reduced price determined by the State Department. This would occur in time to gap-fill the retirement of Australia’s Collins submarines, though mixed crews would likely remain necessary through the 2030s.

The rationale for nuclear submarines

Submarines are very useful when confronting locally powerful adversaries; they can ambush valuable warships and merchant ships while creeping away from threats and remaining unperturbed by radars and massed missiles that threaten surface vessels with detection and destruction from hundreds of miles away.

In the context of U.S.-China competition, anti-submarine warfare is a relative weakness for the latter. A simulation of an attempted invasion of Taiwan run by the CSIS think tank found that submarines and bombers armed with long-range missiles accounted for the majority of PLA shipping losses because neither were vulnerable to the PLA’s thousands of long-range missiles.

However, conventional submarines must periodically surface, or use a snorkel just below the surface, to run an air-breathing diesel engine to recharge the batteries—an indiscretion period in which they’re vulnerable to being detected and destroyed. (Even the snorkel shows up on radar.)

Nuclear-power submarines have a big advantage: they never have to surface! And they can indefinitely sustain high speeds that would rapidly exhaust a conventional submarine’s batteries. The boats have essentially unlimited range and endurance as long as weapons and food last.

These factors make SSNs much more effective over long distances, which matters if Australia pursues a strategy of ‘forward defense’ blocking maritime choke points or supporting allies. But nuclear propulsion remains fantastically expensive, while diesel-electric submarines, though hardly cheap, are more cost-effective for short-range missions such as coastal defense.

Pacific powers Japan, South Korea, and China have begun building conventional submarines using air-independent propulsion (AIP) and/or lithium-ion batteries with substantially greater underwater endurance in the range of a few weeks, albeit traveling very slowly.

AUKUS Political Problems

An immediately apparent issue with the new AUKUS plan is that the U.S. is struggling to produce new submarines fast enough to achieve its own goal of increasing the Navy’s SSN fleet from 49 to 66 or 72 hulls. Production has fallen behind the targeted two-per-year, due to labor shortages, COVID-era bottlenecks, and delays in building new Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines. Giving Australia 3-5 Viriginias would subtract from that SSN fleet just as the service is trying to increase in size.

Meanwhile, Australia will be committing to operating two types of submarines, costlier and less efficient as it requires separate pools of spare parts, training programs, and facilities for maintenance and repair.

Globally, the moving parts in the U.S.-Australian submarine sale appear vulnerable to sabotage should future governments get elected to power who no longer wish to abide by the deal, an acute risk given hostility from the U.S. Navy (which wants to increase its SSN fleet), and Australian shipyards in Adelaide whom in 2021 was promised by former Liberal Prime Minister Scott Morrison they would get to build all eight of Australia’s future submarines. One risk from this view might be that the RAN might reasonably want to stick with the Virginias once habituated instead of devoting huge resources to building Australian SSN(R)s.

Australia’s Collins Class Submarines, HMAS Collins, HMAS Farncomb, HMAS Dechaineux and HMAS Sheean in formation while transiting through Cockburn Sound, Western Australia.

Peter Coates of Australian submarine blog Submarine Matters argues the plan to buy subs directly from the U.S. may be “intentionally unworkable”, arguing “… resistance to Australia buying already built Virginias from U.S. shipyards will be such that Albanese can then honestly claim ‘Oh well! Then we’ll need to wait for the UK-designed SSN(R)s.’”

He projects SSN(R) design will take place in the mid-2030s, the first British hull laid down in 2039, followed by Australia’s indigenous version in 2042, with commissioning into RAN service only coming in 2047.

Coates sees political risks on the other end of the Pacific too: “Might a Republican president (at worst the alliance downgrader Trump?) have different priorities, which might include bowing to already expressed U.S. Navy pressure not to sell Virginias to Australia?”

He also fears plans of mixed U.S.-Australian crews could pose political dilemmas: “What if Washington wants these joint-leased subs to attack Chinese mainland ports while Australia doesn’t want to go to war against China?” He estimates it wouldn’t be until 2038 before enough RAN personnel were adequately trained to provide the majority of the crew for Australia’s Virginias—concerns echoed in an article in the Canberra Times.

Analyst Craig Hooper is more optimistic, arguing at Forbes that the current plan offers a good on-ramp for Australia by giving the RAN years to set up support infrastructure, nuclear safety regulations, and above all to train personnel for the Virginias. He also argues contrary to the conventional wisdom that the U.S. Navy’s capacity to operate submarines is falling behind the production, so giving away a few will create needed breathing room.

Image of Virginia-class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Having outlined costs and risks, it’s worth highlighting some of the benefits of the SSN pact if it is actually implemented: it would result in the U.S. essentially getting a new submarine base on allied soil in the Pacific a healthy distance from most Chinese ballistic missiles.

It would still give Australia SSN-capability relatively quickly while reducing the complexity of that transition by starting with the established Virginia-class instead of a brand-new design, also potentially ‘locking in’ Australia’s transition to SSN operations. Finally, Australia’s SSNs would be more capable of aiding allies in the North and South China Seas, including the dreaded Taiwan conflict scenario, generally resulting in a tighter U.S.-Australia-U.K. alliance.

Time will tell whether the new AUKUS submarine deal between the Anglophone nations can avoid foundering under political, financial, and technical changes to realize its potential.

Author Expertise and Biography

Sébastien Roblin has written on the technical, historical, and political aspects of international security and conflict for publications including 19FortyFive, Popular Mechanics, The National Interest, MSNBC, Forbes.com, Inside Unmanned Systems and War is Boring. He holds a Master’s degree from Georgetown University and served with the Peace Corps in China. You can follow his articles on Twitter.