China’s Legislative Session Delivers Ominous Message to Investors, and Businesses – The annual session of China’s rubber-stamp legislature, the National People’s Congress, left businesses and investors with no shortage of friendly rhetoric. However, beneath the surface of pledges to attract foreign investment and improve the business environment lies a message that should worry the business community.

During the opening session on March 5, outgoing Premier Li Keqiang announced a target growth rate of “around 5%,” underwhelming investors and pundits who had speculated the target might be as high as 6%.

Analysts were quick to attribute the “cautious” target to Chinese officials “playing it safe” after reporting just 3% growth in 2022, falling well short of an ambitious goal of 5.5%. Indeed, China’s economy faces several pressure points in 2023, and officials don’t want to risk missing their target for a second year in a row.

But this narrative is incomplete. While China’s economy has been slowing for the past decade and still faces strong headwinds, last year’s economic woes were largely self-inflicted. This year’s low starting point and the scrapping in December of pandemic controls blamed for the bulk of the economic disruption could likely set the stage for faster growth if China’s leaders wanted it. Yet, Beijing opted for an easy growth target and resisted the kinds of stimulus it previously used to maintain growth in periods of uncertainty.

The reason for these decisions is clear and has been for some time: economic growth is no longer the Chinese government’s end game. It has bigger priorities, many of which aren’t conducive to high growth rates.

To be sure, Beijing’s greatest immediate focus is on ensuring a full economic recovery. The government work report—an authoritative statement of policy that Li presented on Sunday—made this clear. However, the report emphasized not growth but “economic stability.” While this presupposes a stable level of growth, the report also prioritized maintaining stable employment and prices.

This comes as no surprise. China faces record youth unemployment and, while it has managed to keep prices at a reasonable level, the broader world is grappling with the highest inflation in decades. For a government obsessed with preserving social stability, balancing economic growth with creating jobs for new university graduates and keeping the consumer price index increase within 3% (another target presented in the work report) are higher priorities than maximizing investors’ returns. By setting an easily achievable growth target, the government is freeing itself to focus on these issues with greater implications for the Chinese Communist Party’s biggest priority: maintaining its grip on power.

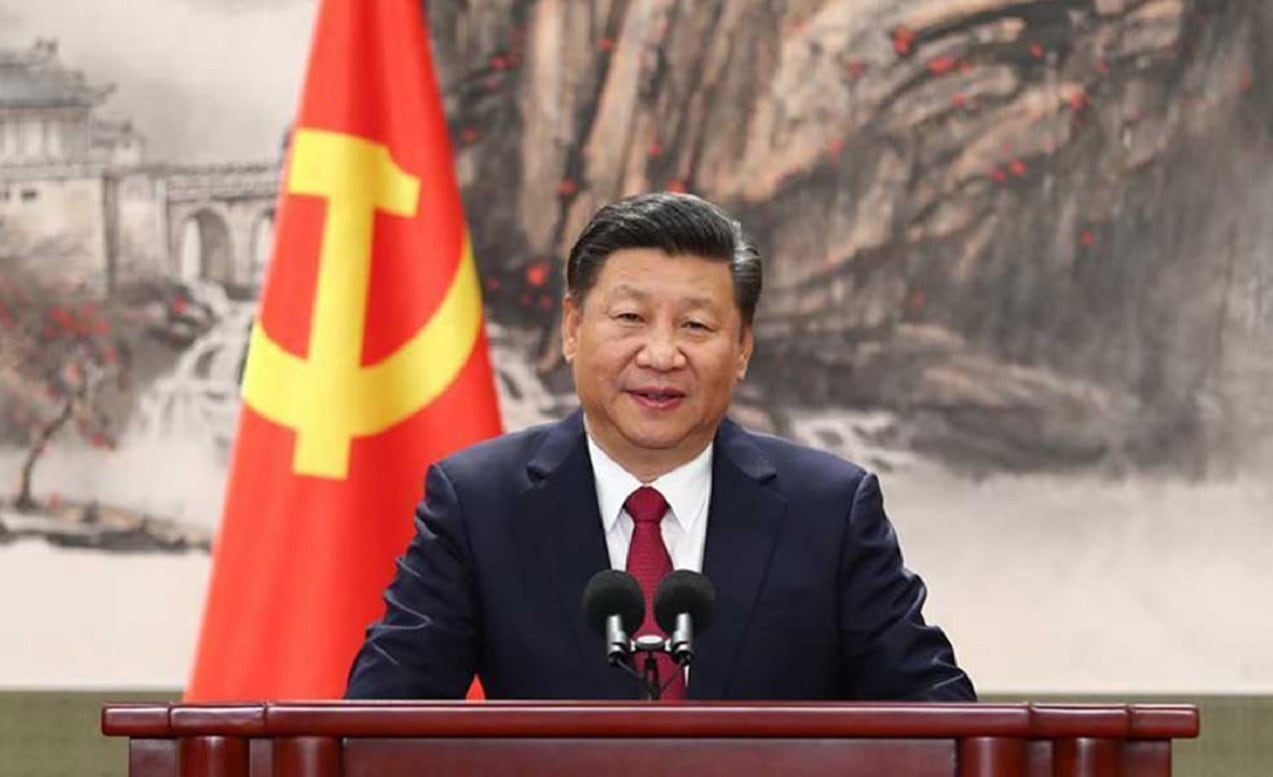

More importantly, Beijing’s manageable growth target for 2023 shows that the government is eager to push along its economic transformation and address what it views as long-term, systemic risks. Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, he has overseen a shift in China’s development paradigm from an almost singular focus on quantitative growth to a pursuit of “high-quality” development aimed at helping China avert the “middle income trap” and consolidate its rise as a global power.

While these objectives cannot be achieved without maintaining a healthy level of economic growth, they also require restructuring the economy in line with China’s long-term goals. These “structural reforms,” as Beijing calls them, require taking on powerful vested interests, often resulting in considerable short-term pain. Importantly, while many of these “reforms” address genuine risks and aim to help businesses in the long run, they often involve regulatory developments that are a far cry from the liberal reforms western governments and businesses would like to see Beijing adopt.

China under Xi has taken a gradual approach to restructuring. It saves the most difficult action for periods when economic growth is stronger than needed and eases off this action when the economy or society become stressed. For example, it was only after far exceeding its growth targets for the first half of 2021 that Beijing intensified its crackdowns on the internet and education sectors in the second half of that year. It rolled back this action in 2022, however, as the residual effects of those crackdowns combined with widespread COVID-19 outbreaks to seriously hamper the economy.

By resisting the temptation to set an ambitious growth target, Beijing is laying the conditions to re-intensify its “structural reforms” at some point in 2023. The government work report confirmed this by declaring the government’s priorities for the year to be “pursuing progress while ensuring stability.” In other words, rather than maximizing growth, Beijing seeks just enough growth to preserve stability while diverting other resources to making progress on longer-term objectives.

As for what this will mean in practice, the work report specifically highlights concerns about the financial, real estate, and the public sectors. Indeed, a slow-burning “cleanup” of the financial sector has been underway for years and seems likely to intensify. A plan to reorganize some government ministries, which was presented during the legislative session on Tuesday, includes the creation of a powerful new financial regulator, further confirming the sector as a likely target.

Beijing will initially have to tread lightly to keep businesses and investors engaged. But its efforts to attract investment and appease businesses are just means to facilitate Beijing’s bigger plan of restructuring its economy in line with its domestic and global ambitions. The days when economic growth reigned supreme in China are long gone. China’s leaders have, once again, signaled they have bigger priorities than keeping investors happy.

Author Biography and Expertise

Michael Cunningham is a Research Fellow in The Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center, where he focuses on China’s domestic politics and foreign policy. Prior to relocating to Washington, D.C. in 2021, Michael spent over a decade in the Greater China region, where he advised multinational businesses on the political, operational, and security risks associated with their business activities in China and Northeast Asia. Michael obtained a bachelor’s degree in international relations from Brigham Young University and a master’s degree in international affairs from American University. He has lived extensively in both mainland China and Taiwan and is fluent in Mandarin Chinese and Portuguese.