The invasion of Iraq in March 2003 was justified by its proponents as a preventive war to shield the United States from a dangerous foreign adversary. Instead, it turned into the quintessential forever war—a geopolitical vortex from which successive US leaders have found it seemingly impossible to break free. The costs to the United States in terms of blood and treasure over the past 20 years have been enormous. The damage done to US soft power, especially in the Middle East and North Africa, is likely irreparable.

Scholars will debate the origins and causes of the Iraq War for a long time to come. But the most obvious (albeit, perhaps, overly charitable explanation) is to take the architects of the war at their word. From this view, the invasion was caused by Saddam Hussein’s stubborn refusal to give UN weapons inspectors unfettered access to sensitive sites in Iraq. In the post-9/11 world, the United States and its allies could not take the risk that weapons of mass destruction might fall into the hands of terrorists. An invasion to disarm and depose the Ba’athist regime—which had a track record of using chemical weapons on the battlefield and against its own people—was the only recourse.

In effect, this was the doctrine of preventive war embraced by President Bush and his advisers. The White House was adamant that the United States was entitled to use force to neutralize foreign threats even in the absence of compelling intelligence that an attack on US interests was imminent. Condoleezza Rice put it succinctly: “We don’t want the smoking gun [that Iraq possessed nuclear weapons] to be a mushroom cloud.”

At the time, most Americans accepted the logic of preventive war. Opinion polling later revealed that many US citizens remained committed to the idea of preventive strikes even after the Iraq War had become a quagmire. Among elites in Washington, however, Iraq soon became byword for blunder. It is perhaps telling that both President Obama and President Trump saw it expedient to claim opposition to the war when running for the White House. Certainly, few elected officials today would regard the invasion as a model for future military interventions.

If there is a silver lining to the Iraq War, then this is it: a legacy that militates strongly against the United States initiating a large-scale land war for many years to come. Even neoconservatives such as Max Boot now regret their support for the invasion of Iraq. The settled wisdom in Washington is that blunt military force is the wrong tool for bringing about major changes to the government, politics, and societies of foreign countries—and rightly so.

But at the same time, the experience of fighting in Iraq has laid bare that the US political system has an alarmingly high tolerance for permanent war—just so long as such conflicts can be kept on the smaller side and mostly hidden from public view. This is a problem. For it is not enough that Washington has rejected the doctrine of preventive war. If Americans are ever to enjoy the fruits of genuine national security, their leaders must repudiate the doctrine of forever war, too.

The acquiescence in constant, low-level warfighting is one of the most insidious legacies of America’s relations with Iraq. It is often forgotten that between 1991 and 2003, US aircraft flew hundreds of thousands of sorties over northern and southern Iraq with the goal of weakening Saddam Hussein’s grip on power and eroding his ability to terrorize vulnerable segments of the Iraqi population. For 12 years, these US forces fired missiles, dropped bombs, destroyed infrastructure, and took heavy fire from Iraqi forces. Viewed in this context, the invasion of Iraq in March 2003 was not so much the beginning of a new conflict as it was the expansion of an existing war—one that had been smoldering since the 1990-1991 Gulf War.

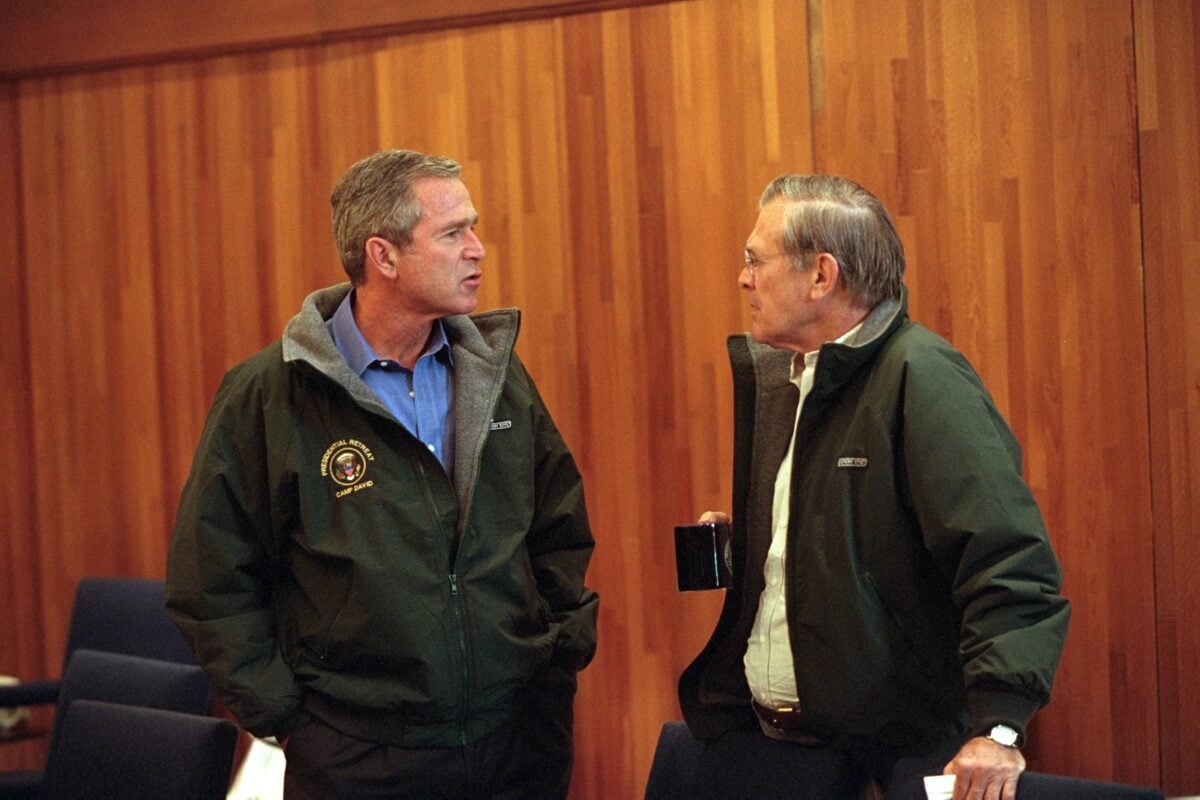

President George W. Bush talks with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld Saturday, Sept. 15, 2001, during a break from a National Security Council meeting at Camp David in Thurmont, Md. Photo by Eric Draper, Courtesy of the George W. Bush Presidential Library

In 2011, US troops ended combat operations in Iraq and withdrew from the country at the behest of the government in Baghdad. President Obama’s exit from Iraq marked the end of a two-decade stretch of US-led military engagement in Iraq. Just three years later, however, Obama ordered the return of US forces to Iraq in the name of stopping Islamic State fighters from overrunning the region. Thousands of US troops were deployed to defeat the militants—a mission that only ended in December 2017.

Since then, US forces have remained stationed in Iraq, mostly serving as advisers and trainers for the Iraqi military. Some 2,500 US personnel are resident in Iraq at any given time. This is hardly a trivial presence, not least of all because Iranian-backed groups attack US forces with some regularity, causing serious injuries and running the perpetual risk of a greater conflagration between Washington, Tehran, and their allies. In January 2020, for example, Iran launched 12 missiles at US bases in Iraq in retaliation for the assassination of Qasem Soleimani, wounding dozens of US military personnel. It is only through sheer fortune that this did not result in a wider war.

Taken together, the United States has been at war in Iraq for 32 years—around 13 percent of America’s history as an independent nation. At present, it shows no signs of exiting the country. On the contrary, the indefinite commitment to militarily policing Iraq seems to have been replicated elsewhere, from Syria to Libya and Somalia to Niger. In all of these countries and more, US soldiers’ lives are being placed at risk for dubious national-security benefits.

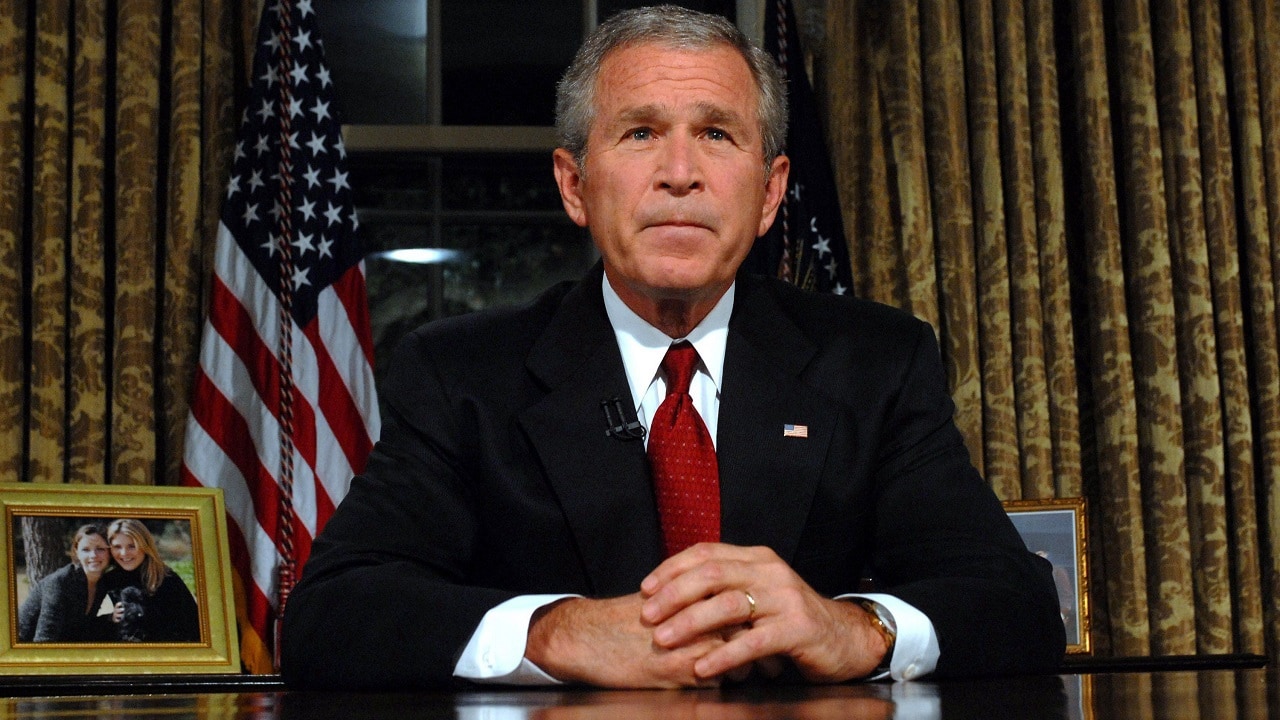

President George W. Bush delivers an address regarding the September 11 terrorist attacks on the United States to a joint session of Congress Thursday, Sept. 20, 2001, at the U.S. Capitol. Photo by Eric Draper, Courtesy of the George W. Bush Presidential Library

The legacy of the Iraq War is complex and still unfolding. But one thing can be said for sure: despite the unpopularity of the war today, the experience of Iraq did not augur a period of wide-ranging retrenchment or restraint for US foreign policy. On the contrary, the consensus that the US military must be omnipresent and all-powerful is as strong as ever.

Has the United States learned anything from its blunders in Iraq? Yes, but not enough. Properly understood, the war in Iraq remains the archetypal forever war—one that ought to be brought to an end sooner rather than later, and never repeated.

Dr. Peter Harris is an associate professor of political science at Colorado State University, a non-resident fellow at Defense Priorities, and a contributing editor at 19FortyFive.