U.S. relations with the Republic of Korea (ROK) have been experiencing severe strains over the past several years. That pattern reached a new level of intensity in April 2023 when leaked Pentagon documents indicated that the United States had been spying on its longtime ally. That revelation likely did not come as a great surprise to President Yoon Suk-yeol’s government. Washington has been caught conducting surveillance on numerous allies over the decades. Two especially notorious incidents, one in 2015, the other in 2021, involved National Security Agency (NSA) operations focused on German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Nevertheless, the latest revelation put Yoon in an awkward position. Korea’s opposition Democratic Party immediately exploited the situation, issuing a statement condemning Washington’s behavior as a “clear infringement” of the ROK’s sovereignty and accusing Yoon of overseeing “lax” security policies. The timing of this scandal also could scarcely have been worse, coming barely two weeks before Yoon’s scheduled summit with Joe Biden.

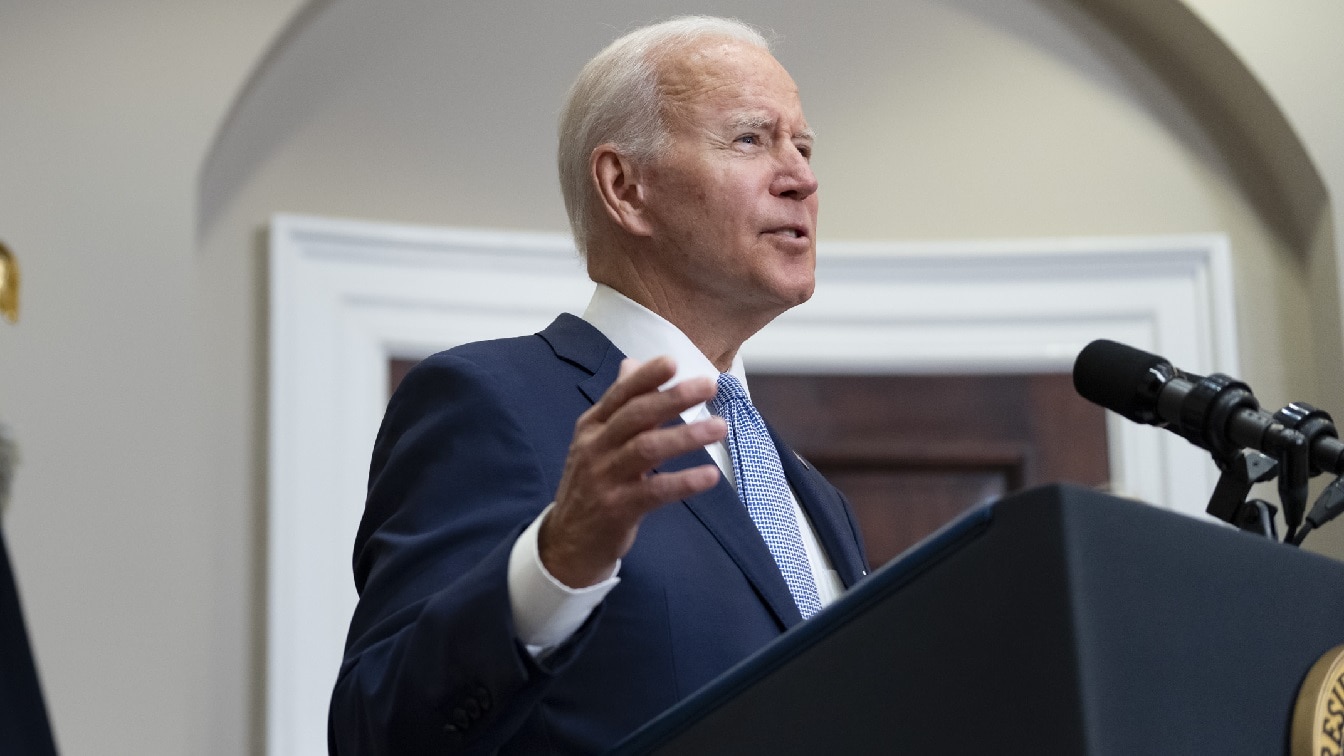

Biden moved to repair the damage as much as possible and to discourage Seoul from pursuing a foreign policy that seemed increasingly independent from Washington’s goals. U.S. leaders were growing concerned that the ROK was flirting with acquiring an independent nuclear deterrent to reduce the country’s reliance on the United States for its security. Prominent members of the American foreign policy community noted that a serious debate on the issue had begun to take place in South Korea.

The joint declaration at the conclusion of Biden’s April 2023 summit meeting with Yoon clearly sought to discourage that option by conveying a more robust U.S. commitment to South Korea’s security, including the symbolic gesture of sending a nuclear submarine to dock in the ROK for the first time since the 1980s. Biden also indicated that Seoul would have greater input into decisions involving the bilateral alliance, including nuclear policy. Whether or not such steps will be sufficient not only to keep South Korea in Washington’s camp, but to induce ROK leaders to commit their country to back Washington’s overall agenda in East Asia remains uncertain.

The main source of discord is policy toward the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As Donald Trump’s administration attempted to do, the Biden administration seeks to enlist South Korea in a de facto containment policy directed against Beijing. That approach has two main elements: encouraging allies to reduce their economic and technological dependence on the PRC (so called “decoupling”), and getting a commitment to help the United States defend Taiwan, if the PRC decides to use force against the island to compel reunification with the mainland.

Yoon’s predecessor, Moon Jae-in, firmly resisted that courtship, and even though Yoon was widely expected to be more hardline and pro-U.S., the trajectory of South Korean policy toward China has not changed that much. Seoul still would prefer to avoid antagonizing the PRC regarding either economic decoupling or Taiwan. China is a major ROK trading and investment partner, and Seoul needs the PRC to discourage North Korea from engaging in rash actions.

As Cato Institute senior fellow Doug Bandow points out, Seoul especially has major incentives not to antagonize Beijing militarily. “South Korean military facilities would be targeted by Chinese missile attacks to prevent their use by U.S. forces. If Seoul and other allied states committed to war on Washington’s command, Beijing would have an incentive to strike preemptively if conflict loomed.”

That reality largely explains Yoon’s refusal to make a firm commitment to Washington regarding policy toward Taiwan, North Korea, or other matters that could lead to a collision between the ROK and the PRC. Bandow points out that Yoon “appears to have edged back from the U.S. on THAAD deployments, Quad membership, semiconductor chips, and Taiwan’s defense. The Quincy Institute’s James Park likewise observes that the ROK leader “looks far from [being] a China hawk.”

Such major differences between Washington and Seoul about relations with China mean that Biden’s concessions at the recent summit will have only limited beneficial effect. The ROK is not about to enlist in a U.S. crusade against China, especially regarding the issue of defending Taiwan. Despite Biden’s best efforts, the joint summit declaration merely puts a band-aid on a festering wound in the bilateral alliance.

MORE: The F-35 Now Comes in Beast Mode

MORE: Why the U.S. Navy Tried to Sink Their Own Aircraft Carrier

A 19FortyFive Contributing Editor, Dr. Ted Galen Carpenter is a senior fellow at the Randolph Bourne Institute and a senior fellow at the Libertarian Institute. He also served in various policy positions during a 37-year career at the Cato Institute. Dr. Carpenter is the author of 13 books and more than 1,200 articles on international affairs. His latest book is Unreliable Watchdog: The News Media and U.S. Foreign Policy (2022).