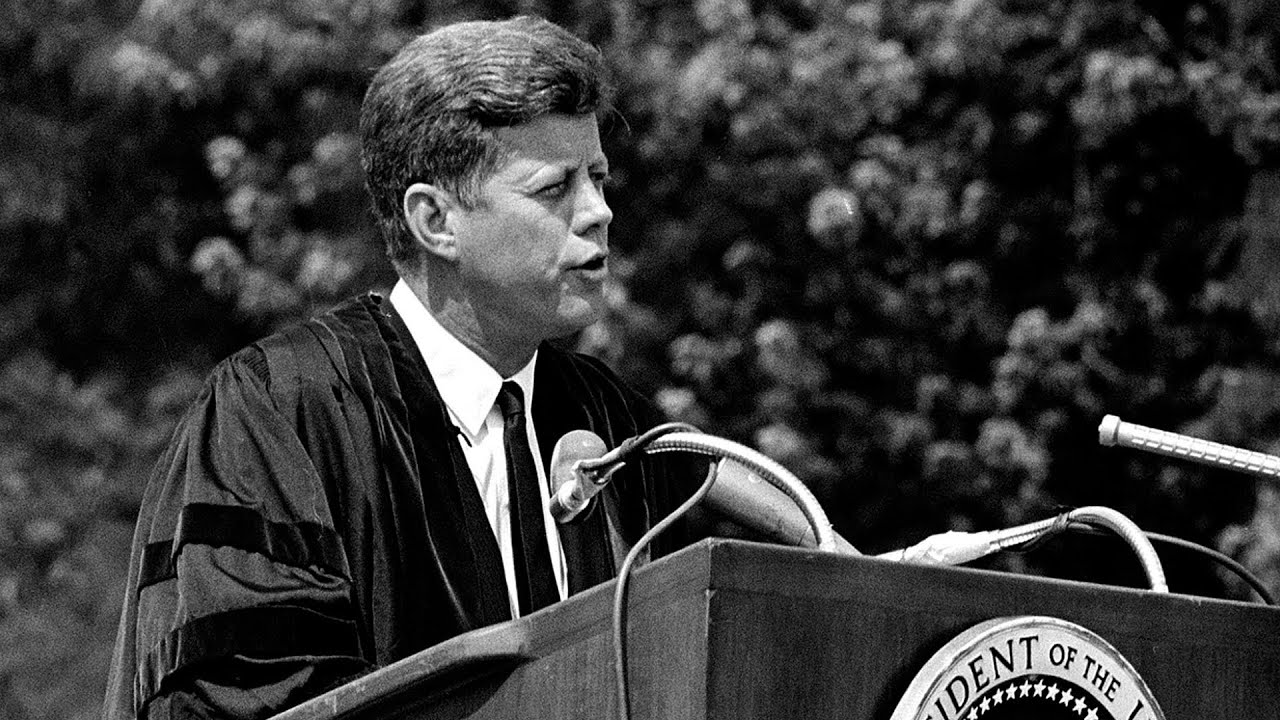

Today marks the 60th anniversary of perhaps the most remarkable speech President John F. Kennedy ever gave.

In it he laid out, from a position of unrivaled American strength, a path to peaceful coexistence with our most hated, powerful and feared enemy, the Soviet Union. Whatever hope was kindled on that day was snuffed out mere months later, however, as Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963. Such principled, passionate desire for peace has not been seen in the White House since. For the sake of our continued security and prosperity, the United States today urgently needs to resurrect that spirit.

The Vital Call for Peace

Kennedy delivered the keynote address for the graduating class at American University on June 10, 1963. He stunned many observers in both Washington and Moscow at the time by laying out a comprehensive argument for peace between the two archrivals and advocating a reduction in nuclear weapons, starting with a test ban treaty. Unsurprisingly, some criticized the president at the time for believing peace could ever come between two such staunch opponents. Such obstructive thinking remains pervasive in the United States today.

Too often we view those who advocate for peace as being weak, insufferably naïve to the harsh realities of the world. I approach the topic from the exact opposite perspective. As I routinely write and argue on televised appearances, we must see the world as it is, taking it in all its harsh, cruel realities, and seek to craft a quality and sustainable life for American citizens in spite of those realities. I have personally seen the devastation war imposes on its victims, fighting through four combat deployments during my 21-year career in the Army.

Further, my advocacy for peace is grounded on the firm understanding of the reality that there are evil men in this world and that at times it is necessary to fight to keep one’s family and nation safe. I unapologetically argue that maintaining a strong and capable national defense capacity is vital. In 1963, Kennedy had this same experience and motivation.

Fears We Should Keep

The 35th president was a combat veteran of World War II and saw the utter devastation that resulted from the use of nuclear weapons. He wisely feared the catastrophic consequences of nuclear war. Many today have lost that very healthy fear, including many of those who should most acutely understand the dangers. Instead of leading the way to explain the cataclysmic risks of any nuclear exchange and being passionate advocates for finding peaceful coexistence with our nuclear-armed adversaries, too many of today’s retired generals seem to go out of their way to dismiss the concerns.

Former four-star General Ben Hodges, for example, routinely claims Russia would never use nuclear weapons and aggressively advocates the U.S. supporting Ukraine with the most offensive and lethal aid and weaponry, seemingly unconcerned about the possibility Russia might resort to nuclear weapons if it were to ever be in danger of losing. It was precisely the recognition of this dynamic that in part animated Kennedy to deliver his peace speech 60 years ago.

To understand the gravity of Kennedy’s speech at American University, it is crucial to understand the context. First, it was only 18 years since World War II had ended with the nuclear detonations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was two years since the USSR had tested a 100 megaton nuclear bomb (3,800 times more powerful than the Hiroshima blast), and a mere eight months after the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, during which the world was a hair’s breadth away from nuclear Armageddon. Far from wanting to talk peace, most in America wanted to build up defenses, especially our nuclear arsenal, to be prepared for a war against the USSR.

Further, the United States was then the unrivaled economic power on the planet. It had remained unscathed during World War II and was an engine of economic growth throughout the free world. The United States had the most powerful conventional army, navy, and air force in the world, and our nuclear arsenal was three times larger than the Soviets’ stockpiles. From this position of unequaled power, Kennedy could have pressed to expand America’s economic and military advantages in an effort to increase deterrence against Moscow. Instead, he chose a much more principled, courageous – and effective – path.

The Peace That Makes Life Worth Living

In his remarkable speech, Kennedy didn’t flinch on calling out Soviet behavior or threats. He did not downplay the risk to American and global security represented by the USSR. Yet he also avoided the hubris that has afflicted most of the U.S. and the West over the past several decades. He called for self-reflection by all Americans. Among the most substantive of his many excellent points, Kennedy said:

-

- What kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, the kind that enables men and nations to grow and to hope and to build a better life for their children — not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women — not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.

- Today, should total war ever break out again — no matter how — our two countries would become the primary targets. It is an ironic but accurate fact that the two strongest powers are the two in the most danger of devastation. All we have built, all we have worked for, would be destroyed in the first 24 hours.

- For we are both devoting massive sums of money to weapons that could be better devoted to combating ignorance, poverty, and disease. We are both caught up in a vicious and dangerous cycle in which suspicion on one side breeds suspicion on the other, and new weapons beget counterweapons.

- Let us examine our attitude toward peace itself. Too many of us think it is impossible. Too many think it unreal. But that is a dangerous, defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war is inevitable — that mankind is doomed — that we are gripped by forces we cannot control. … But (I also warn) the American people not to fall into the same trap as the Soviets, not to see only a distorted and desperate view of the other side, not to see conflict as inevitable, accommodation as impossible, and communication as nothing more than an exchange of threats.

And lastly:

- This generation of Americans has already had enough — more than enough — of war and hate and oppression. We shall be prepared if others wish it. We shall be alert to try to stop it. But we shall also do our part to build a world of peace where the weak are safe and the strong are just. We are not helpless before that task or hopeless of its success. Confident and unafraid, we labor on — not toward a strategy of annihilation but toward a strategy of peace.

So many of the themes Kennedy articulated back then are especially relevant today. The need to recalibrate our actions and attitudes towards Russia is urgent. The animosity and hatred among many in both Russia and the United States against one another are as acute as they have been in many decades. Talk of nuclear escalation in the Russian-Ukrainian war, by both Western and Russian voices, is far too cavalier.

Presidential Obsessions With War

The ramifications of any nuclear exchange between Moscow and Washington are just as catastrophic today as in 1963, and the need to lower tensions and seek peace is more urgent than ever. Yet there has been little interest in decades from any occupant of the White House in pursuing a difficult peace with Russia.

Every occupant of the Oval Office since Kennedy died has been more interested in tying his legacy, to one degree or another, to being a “wartime president.” Though Jimmy Carter does deserve credit for trying to broker peace in the Middle East (and won a Nobel Peace prize for it after leaving office), even his record on war and peace was mixed while in office. After 9/11, however, it seems every president has considered it a necessity to bolster his legacy by wanting to show military strength above any interest in peace.

The efforts U.S. presidents since 2001 have made toward peace have usually been characterized by trying to coerce other global players to adopt policies and behaviors beneficial to us, irrespective of how or whether it may benefit another party. Engagement via diplomacy, allowing each side to get something valuable to itself in a final settlement, has almost vanished.

The result has often been that because of our great economic and military power, we have frequently gotten our way. But at a cost. Anger and resentment has been building against our country for decades, and now as other players are growing in power of their own, they are demonstrating they are less and less willing to bend to our will and more willing to pursue their own interests, which increasingly come at our expense.

Where Is the Modern-Day Kennedy?

It has rightfully been said that with great power comes great responsibility. I would add to that, however, that to wield great power also requires wisdom. We must recognize that to rely purely on American military and economic power to try and compel all other nations to submit to our preferences on all matters is ultimately self-defeating. Wisdom recognizes that sometimes the most powerful and persuasive means to achieving beneficial outcomes for America involve humility, the willingness to give as well as take, and recognizing that sometimes we must give a tactical win up front in order to gain a bigger strategic prize later.

As the war between Russia and Ukraine rages on, the stakes for global security keep rising. Russian, American, and Western actors increasingly warn of the potential for nuclear escalation. Yet thus far the only answer from any party seems to be more threats, more weapons, and more ammunition. Putin shows no interest in even having peace talks. Zelensky rejects any consideration of a negotiated settlement. The United States only says it will support Ukraine militarily “for as long as it takes.” To break this impasse, someone must become a modern-day Kennedy.

To seek peace, we must overcome the perception that to talk about anything besides war and threats is somehow weak. To the contrary, for the United States to seek peace from a position of great strength would demonstrate wisdom and give our country the best chance to prevent further war and ensure continued national security and economic prosperity for our countrymen and allies.

To succeed, we would have to display some humility and accept that to find an end to this current war, every player is going to have to come away with something it considers valuable. That means no one is going to end up with everything they want. Ideally, Ukraine would end up with all of its territory, all the way to the 1991 borders, and Russia would end up with a solution that satisfied Moscow’s long-term security requirements. But an ideal outcome is not realistic in the current environment.

With patience, a great deal of hard work, and an understanding that no one will be happy at the end, a negotiated settlement leading to eventual peace is attainable. First and foremost, that will require extraordinary leadership by the United States, likely meaning the president. Without first having a desire to seek peace, no negotiated solution is possible, and the matter will continue to be settled on the battlefield. That likely means considerably more killing and more destruction, with no end in sight, for the people of Ukraine.

Worse, in perpetuating a conflict in which no side is willing to consider ending the war on anything other than maximalist terms of its choosing, the risk of catastrophic nuclear escalation will remain an open threat. If any party eventually uses so much as a tactical nuclear device — resulting either by accident, miscalculation, or a foolish act by one party or another — the cost in lives could be in the tens or hundreds of millions. Taken far enough, the possibility of mutual assured destruction cannot be discounted.

Sixty years ago, John F. Kennedy recognized the potential existential consequences of continued animosity between the USSR and the United States. Those same terrifying potentials exist today. It is more crucial than ever that leaders and people soberly recognize what is really at stake and seek to develop a spirit of peace while there is still time. Ignore the dangers and retain our current force-only posture, and we may one day lose everything.

A 19FortyFive Contributing Editor, Daniel L. Davis is a Senior Fellow for Defense Priorities and a former Lt. Col. in the U.S. Army who deployed into combat zones four times. He is the author of “The Eleventh Hour in 2020 America.” Follow him @DanielLDavis.