After World War II, the United States military disbanded units dedicated to sabotage, guerilla warfare, and clandestine operations. These units put into action the very outside-the-box thinking that proved crucial during the war. After more than a decade, President John Kennedy identified an irregular warfare gap and took action to ensure that the military developed and maintained a special operations capability. This took place at a time when the Cold War was in full swing and the nuclear arms race was the central focus.

The irregular warfare of special operations was forced to the margins as the United States built a massive nuclear arsenal. After all, nuclear war with the Soviets appeared imminent. Fortunately, the Cold War ended as it began, and neither a nuclear holocaust nor a Soviet invasion of Europe occurred.

A New Era Demands New Approaches

Near the end of the Cold War, Congress passed the Goldwater-Nichols Act, which sought to compel the services to integrate their approaches to warfare. It also authorized the establishment of US Special Operations Command (SOCOM). The creation of SOCOM came in response to the failure of Operation Eagle Claw (1979) — the American effort to rescue hostages from Tehran.

Over the next three decades, SOCOM personnel developed comprehensive plans and standard operating procedures, as well as collecting immense amounts of critical data, trends, and lessons learned to retain the competitive advantage at tactical, operational, and strategic levels in the fight against America’s adversaries. As the era of combat geared to countering violent extremism concludes, a new direction for the U.S. government and military is emerging — great power competition.

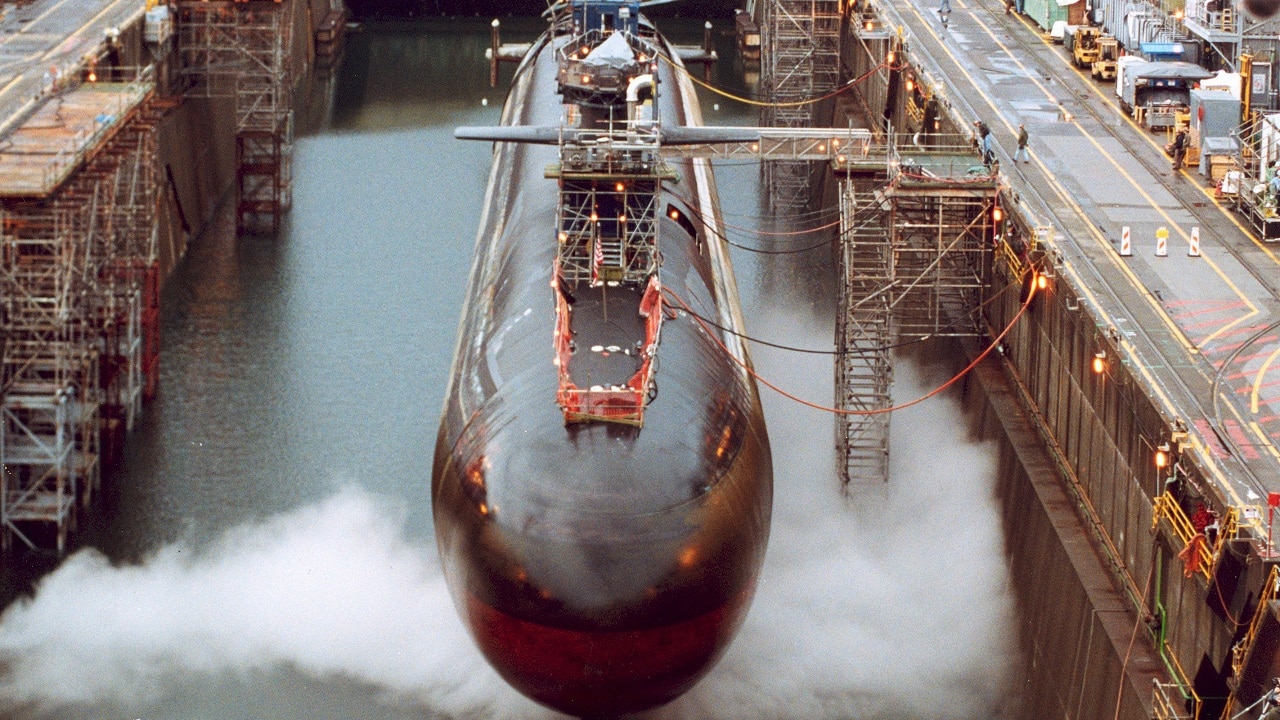

With the nation’s nuclear enterprise finally receiving some due attention and funding, it is also time to bring military special operations organizations into the discussion as they shift to a greater focus on Russia, China, and North Korea. Given the strengths of special operations, and SOCOM leadership’s effort to move from a “supported” to a “supporting” role, there is a significant opportunity to demonstrate special operations’ value in an integrated deterrence strategy that is still ill-defined.

Are the nation’s military leaders prepared to construct a fully integrated military strategy that integrates deterrence across domains with whole-of-government capabilities? The jury is still out.

Integrating Two Communities to Strengthen Deterrence

While it seems unlikely that special operations units would face a similar fate to their World War II predecessors — absorption into conventional forces — relegating them to counterterrorism missions or other poorly defined supporting roles would be a mistake.

What is perhaps a more useful approach is to take the lessons learned from special operations’ 20-year fight to counter violent extremism and see where they might be applied to integrated deterrence and to the emerging tripolar nuclear competition between the United States, Russia, and China. Any new war will only be won through innovative programs, out-of-the-box-thinking, and fully integrating cross-functional problem solvers—a strength of special operations.

The process begins by considering how barriers, assumptions, and biases within special operations and nuclear deterrence operations communities discourage professionals from integrating and leveraging their expertise to develop and put into action a fully integrated military deterrence strategy. Admittedly, this sounds like something straight from an Army training course, but the point is clear. Unidentified barriers, biases, and assumptions make any successful cultural integration extremely difficult. And in this case, these are two of the least understood and most reclusive military communities.

Some of the perceived differences between the two communities are illustrative. First, special operations missions are mostly tactical, but often have strategic implications. Nuclear operations are always strategic. Second, special operators work in the grey zone and have a “get it done at any cost, cowboy” mentality. Nuclear operations strictly follow technical order checklists and are “safe, secure, and effective robots.” While these perceptions are only partially correct, both communities live in a world where mission failure is not an option.

Integrating two communities that operate on opposite sides of a linear warfighting spectrum seems difficult, but what if Western linear thinking is the root cause of this difficulty? Perhaps integration should be reframed along an Eastern, circular-infinite-spectrum thought lens.

If special operations and nuclear deterrence operations are placed on a spectrum of conflict, it is easy to think they sit at opposite ends. However, if you take an Eastern view that employs a circular-infinite-spectrum, it is possible to see the line bend inward, with one end touching the other. In short, it is possible to integrate both approaches to warfare as a means of achieving integrated deterrence.

Given the varying interests of our adversaries, credible deterrence will look different to China than it does to Russia or North Korea. Integrated deterrence is thereforenot a prefabricated, one-size-fits-all solution. Deterrence tactics without a deterrence strategy are just as useless.

Understanding the complexity of the problem-set is critical, if exceedingly difficult. U.S. Strategic Command alone cannot achieve this objective, because it is only one piece of the deterrence puzzle.

Special operations conduct irregular warfare using the overarching doctrinal tenets of “deter, assure, dissuade, deny, and strike.” Nuclear operations’ doctrinal tenets are exactly the same. The main difference lies in that special operations activities are a strategic deterrence microcosm, and nuclear operations activities are the macrocosm. Though traditionally perceived to operate on different ends of the linear warfighting spectrum, each prosecutes military operations through the same doctrinal lenses.

All of this is to say that it is time special operations and nuclear deterrence operations join forces to develop a meaningful strategy to deter America’s adversaries.

Major Daniel S. Adams spent the first decade of his career as an enlisted Air Force Special Tactics Combat Controller. He is now an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) nuclear operations officer and a former instructor at the USAF Weapons School. Dr. Adam Lowther founded the Air Force’s School of Advanced Nuclear Deterrence Studies (SANDS) and taught planning at the US Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies.

The views expressed in this article represent the personal views of the authors and are not necessarily the views of the Department of Defense, the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. Government.