On Saturday Russia was thrown into disarray by a failed mutiny by Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of the Wagner mercenary group.

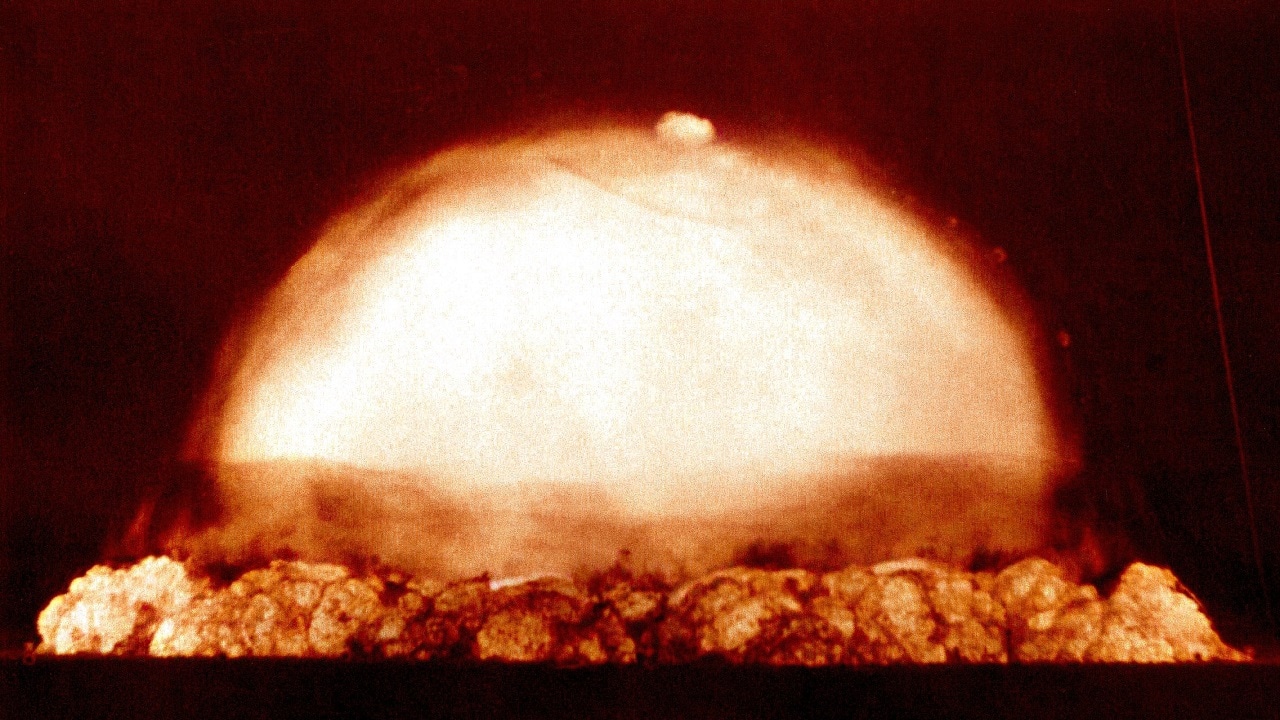

The mutiny, which showed some of the cracks in the edifice of the Russian state that Vladimir Putin has created, triggered some concerns over the status of Russian nuclear weapons.

The idea of combatants in a civil war seizing nuclear weapons is one of the nightmare scenarios for security analysts.

Of course, this is hardly the first attempt at a violent transfer of authority in a nuclear power country; most countries with nuclear weapons have suffered from some kind of extra-legal leadership crisis.

France

On February 13, 1960, France detonated its first atomic device at a remote site deep in the hinterlands of Algeria. The test was politically awkward because Paris was in the throes of a struggle with both the community of French citizens in Algeria (pied noir) and with the Algerian independence movement (FLN). A little over a year later, as the intentions of the De Gaulle government to grant Algeria its independence became apparent, a group of French generals launched a coup intended to forestall the cession by ceasing the French state. The coup failed to trigger a general uprising in either Algeria or metropolitan France and collapsed after several days.

USSR and Russian Federation

Probably the scariest coup in the history of nuclear weapons happened in the autumn of 1991 when a group of Soviet generals made a belated effort to turn back the collapse of the Soviet Empire. The coup plotters took power for about three days, putting President Mikhail Gorbachev under house arrest and contesting control of Moscow and other parts of the country. U.S. policymakers panicked, but kept their panic as quiet as possible in order to avoid upsetting the development of events. The failure of the coup precipitated the collapse of the Soviet Union, driving the constituent republics of the USSR into independence. Gorbachev reassumed power but for only long enough to preside over the end of the state that he led.

The Russian Federation inherited most of the Soviet nuclear arsenal and much of its instability. In the autumn of 1993, a constitutional crisis broke out into open fighting in Moscow between partisans of the Russian Duma and President Boris Yeltsin. Yeltsin defeated his opponents and maintained control of Russia’s nuclear arsenal throughout the crisis.

China

The People’s Republic of China went nuclear in 1964, on the eve of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. In September 1971 the divide between Mao Zedong and one of his chief lieutenants, Lin Biao, had become unbridgeable. Details of the “Lin Biao Incident” remain hazy, but Chinese authorities assert that Lin attempted to seize power from Mao, then tried to flee to the Soviet Union when the attempt went badly. Lin’s plane crashed in Mongolia, killing everyone on board.

Upon the death of Mao Zedong control of the Chinese state briefly seemed up in the air. The “Gang of Four,” including Mao’s widow Jiang Qing, made a play for power in Beijing, establishing control over the city and challenging the broader leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). However, at this time the power base of the Chinese Communist Party was tied up tightly with regional military control, putting stark limits on the ability of any outsiders to seize control of the state. The Gang of Four was arrested after a month-long contest for influence over the People’s Liberation Army. Access to nuclear weapons was apparently never in question, remaining in the hands of army officials.

Pakistan

One of the major concerns about Pakistan’s development of nuclear weapons involved perceptions of its unstable political system. Pakistan suffered many coups and coup attempts before it went nuclear, and perhaps more ominously suffered catastrophic military defeat and dismemberment at the hands of its neighbor.

In October 1995, a group of army officers tried and failed to overthrow President Benazir Bhutto. In 1999 Pakistani General Pervez Musharraf overthrew Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in a coup precipitated by the latter’s effort to arrest the former. This coup caused considerable consternation in the West, in large part because there was uncertainty about the nature and structure of Pakistan’s systems of command and control. The fact that the state was taken over by the chief of the armed forces offered some solace, however, as the fundamental lines of authority over nuclear weapons remained unchallenged.

United States

On January 6, 2021, presiding U.S. President Donald Trump attempted an autogolpe, an extra-legal effort to remain in power despite losing the 2020 Presidential election. Trump’s effort foundered quickly, although he remained Commander in Chief for another two weeks. The military did not participate in the coup and Congressional certification of the election proceeded with only a small delay. The situation remained tense for the remainder of Trump’s term, but on January 21 authority over nuclear weapons peacefully passed to President Joseph Biden.

What Should We Think?

Nuclear weapons have not granted their owners domestic serenity or immunity from domestic unrest. On more than one occasion, control over nuclear weapons has been at stake during violent efforts to change the government. Only Britain, Israel, North Korea, and India have avoided a violent domestic incident since going nuclear, and in India’s case, the emergency came very close. Fortunately, this disorder has yet to lead to a situation in which nuclear weapons were either up for grabs or ended up on different sides of a civil conflict. However, as the situation in Russia over the past few days has demonstrated, nuclear weapons and domestic instability are two tastes that most definitely do not go well together.

A 19FortyFive Contribuiting Editor, Dr. Robert Farley has taught security and diplomacy courses at the Patterson School since 2005. He received his BS from the University of Oregon in 1997, and his Ph. D. from the University of Washington in 2004. Dr. Farley is the author of Grounded: The Case for Abolishing the United States Air Force (University Press of Kentucky, 2014), the Battleship Book (Wildside, 2016), Patents for Power: Intellectual Property Law and the Diffusion of Military Technology (University of Chicago, 2020), and most recently Waging War with Gold: National Security and the Finance Domain Across the Ages (Lynne Rienner, 2023). He has contributed extensively to a number of journals and magazines, including the National Interest, the Diplomat: APAC, World Politics Review, and the American Prospect. Dr. Farley is also a founder and senior editor of Lawyers, Guns and Money.