By virtue of the fact that Benito Mussolini’s Italy being the first Axis power to capitulate during the Second World War, there’s an enduring misconception that “Il Duce’s” troops were universally cowardly and weak-willed fighters. Fortunately, there is a YouTube video out there titled “Common Myths about the Italian Army most Casual Historians Believe,” which casts the light of truth on that misconception.

The then-Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina; literally, “Royal Navy”) produced its fair share of fierce warriors and fine weapons system as well.

At the small end of size scale, you had Regia Marina frogmen such as the 10tjh Light Flotilla (Decima Flottiglia Motoscafi Siluranti [MAS]), which racked up an impressive tally of 28 Allied ships sunk or damaged (including 111,527 tons of merchant shipping).

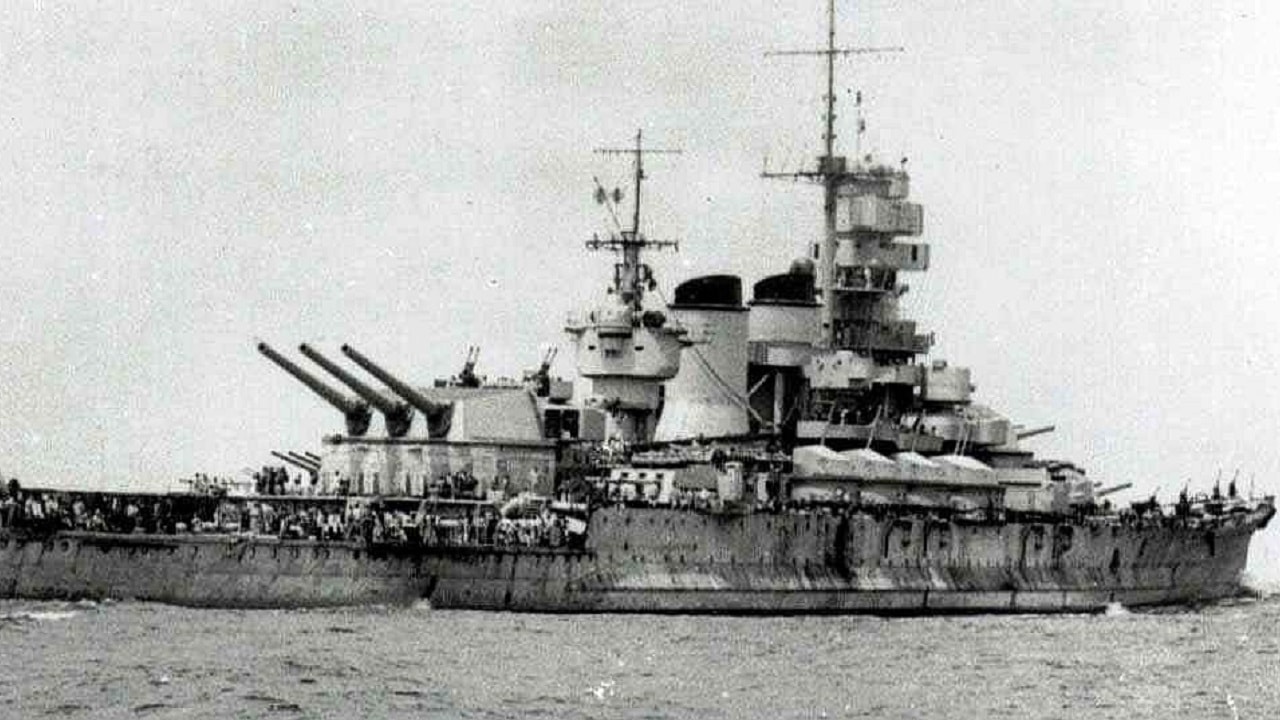

At the opposite end of the size scale, the Royal Italian Navy produced some fine battleships, including the current subject at hand, the Vittorio Veneto.

Vittorio Veneto Early History and Specifications

The ship’s namesake is indeed a proud one in Italian military history, as she was named for a major Italian military victory in the First World War; taking place from 24 October to 4 November 1918 (a mere one week before the end of the so-called “War To End All Wars”), this battle helped bring about the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Vittorio Veneto was built by the Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adtriatico (C.R.D.A; “United Shipbuilders of the Adriatic”) in the northeastern seaport city of Trieste; her keel was laid down on 28 October 1934, followed by her launching on 25 July 1937, and commissioning on 28 April 1940. She was one of four battleships of the Littorio class.

The main guns of Vittorio Veneto were nine 15-inchers divided amongst triple-barreled turrets, two fore and one aft. These were backed up by a bristling secondary battery of twelve 6-inch guns, four 4.7-inch guns, twelve 3.5-inch antiaircraft guns, twenty 37mm guns, and twenty 20mm guns (how’s that for “20/20 vision,” eh).

Other specifications included a hull length of 780 feet 1 inch, a beam width of 107 feet 8 inches, a draft of 31 feet 6 inches, and a fully-laden displacement of 45,237 long tons. Max speed was 30 knots. Crew complement was 1,950 commissioned officers and enlisted men. At its thickest point, the main armor belt was 14 inches.

Operational Service

During WWII, the Vittorio Veneto served as the flagship of the Regia Marina’s Mediterranean Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Angelo Iachino (1889-1976).

The killing or capture of the Vittorio Veneto became a near-obsession of the Royal Navy’s Admiral Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham (1883-1963), Commander-in-Chief of Great Britain’s Mediterranean fleet, who, during the Battle of Cape Matapan from March 27-29, 1941 — which was Italy’s greatest defeat at sea – came “close, but no cigar.”

In that epic engagement, the Regia Marina lost three heavy cruisers – the Zara, Pola, and Fiume – and two destroyers – the Alfieri and Giosuè Carducci – along with 2,400 men, but the Veneto managed to escape with a single torpedo hit from a Fairey Swordfish biplane; in turn, the Veneto’s antiaircraft gunners inflicted the Brits’ only casualties of the battle by shooting down the plane and killing its crew of three. In his 1981 book “The Mediterranean” – part of the excellent Time-Life Books World War II series – military historian A(ddison) B(eecher) C(olvin) Whipple (who had served as Life Magazine’s Pentagon correspondent during WWII) recounts Admiral Cunningham’s obsession thusly: “Still, Cunningham refused to give up a prize as great as the Vittorio Veneto. He listened to the objections and snapped, ‘You’re a pack of yellow-livered skunks! I’ll go and have my supper now and see after my supper if my morale isn’t higher than yours.’ It had been a long and difficult day.

Veneto was also lucky enough to survive several other close calls: (1) the November 1940 Swordfish raid on the Italian fleet Taranto Harbor (a raid which ended up as an unintended catalyst for the Pearl Harbor raid); (2) a torpedoing by the British submarine HMS Urge; and (3) severe damage in an Allied bombing raid on La Spezia in June 1943. In turn, she showed she could dish out punishment in addition to taking it; during the Battle of Cape Spartivento, she damaged the light cruiser HMS Manchester.

Post-WWII Fate

The MilitaryFactory.com website picks up the story from here:

“With the Italian surrender in September of 1943, Vittorio was relocated to Malta for its surrender and unsuccessfully attacked by German warplanes while en route…She was directed towards Alexandria and was later moved to the Suez Canal where she was laid up until October 1946. Upon allowed entry [sic] back into Italian waters, she was handed over to the Britain [sic] as a war prize and stricken from the naval register on February 1st, 1948. Her hulk was then sold for scrapping between 1948 and 1960 and her naval history officially ended. Some of her guns were used as coastal batteries by Yugoslavia and survived until the 1990s.”

Image: Creative Commons.

Image: Creative Commons.

Christian D. Orr is a former U.S. Air Force Security Forces officer, Federal law enforcement officer, and private military contractor (with assignments worked in Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kosovo, Japan, Germany, and the Pentagon). Chris holds a B.A. in International Relations from the University of Southern California (USC) and an M.A. in Intelligence Studies (concentration in Terrorism Studies) from American Military University (AMU). He has also been published in The Daily Torch and The Journal of Intelligence and Cyber Security. Last but not least, he is a Companion of the Order of the Naval Order of the United States (NOUS).

Note: Images are of the Roma, the same Italian battleship class discussed here.

From the Vault

The Navy Sent 4 Battleships To Attack North Korea

‘Sir, We Hit a Russian Submarine’: A U.S. Navy Sub Collided with a Nuclear Attack Sub