Napoleon stated that “amateurs discuss tactics,” whereas “professionals discuss logistics.” Centuries later, the war in Ukraine has once more illustrated his point. Despite a larger and technologically superior force, the Russian military has underperformed through poor preparation, insufficient training, and inadequate logistics. A force that cannot be properly resupplied with fuel, munitions, ammo, and rations will suffer, no matter how large it is.

The lesson applies to other militaries in different geopolitical contexts. For instance, the Indo-Pacific is a vast theater — its expanse provokes worries about the current and projected size of the U.S. Navy. Indeed, Military Sealift Command has been told that the surface fleet would be unable to provide merchant and oiler escorts in the event of a conflict. At-sea refueling and rearming will be critical in the region — China has enough ballistic missiles to hold at risk and neutralize American bases and logistical infrastructure in the Indo-Pacific. Even if forces fight through and gain a foothold within the Chinese anti-access, area denial bubble, how will they continue to fight if logistical ships and L-class surface ships are unable to follow?

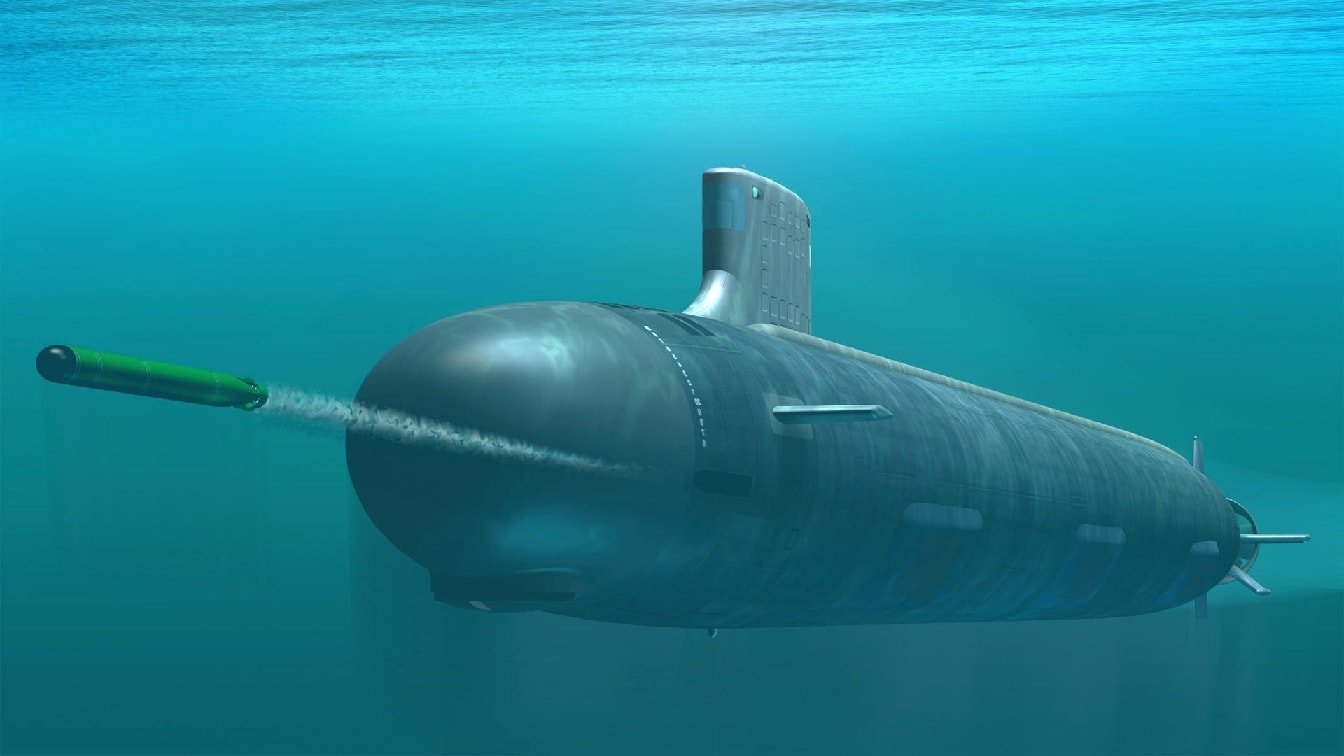

This potential challenge could be solved by a logistics variant of the Columbia-class submarine.

An Idea With Precedent

Submarine-based logistics might sound like a novel concept, but it has been used before. During the early stages of World War I, while the United States was still neutral, Germany turned to unarmed, merchant variants of its U-495 U-boats to twice defeat the British blockade. The Deutschland completed two voyages, to Baltimore and New London, carrying more than 700 tons of cargo each way. The Bremen was lost at sea in between the two voyages of her sister boat. Germany ended these merchant runs after the United States entered the war on the side of the Allied powers.

The concept evolved during the Second World War. The Germans, Americans, and Japanese all developed and employed submarine-based logistics. The Germans developed fuel variants — called milch cows — as well as cargo variants of their U-boats that saw heavy use during the U-boat campaign in the Atlantic. The Japanese used submarines to tow cargo canisters to garrisons on cut-off islands that were not assaulted during the American island-hopping campaign. The United States used submarines to resupply a stranded garrison in Manila Bay after the Japanese overran the Philippines.

However, despite designs and even completed platforms, none of the above countries successfully produced a dedicated logistics submarine during the war.

Changing the Submarine Calculus

As submarine technology grew in sophistication and cost, the return on investment from potential modern logistics submarines was too low to consider development. The rapid growth in technology and the deployment of anti-air and anti-ship coastal missile batteries in support of anti-access, area denial tactics change this calculus, however — as does the looming threat of hypersonic weapons. U.S. and allied surface fleets will likely struggle to maintain sea control when pitted against the shore- and ship-based weapons of the rapidly growing and modernizing People’s Liberation Army Navy. The U.S. Navy would be wise to develop a logistics platform with a higher probability of survival and a much lower detection of risk than surface ships. Budgetary constraints probably rule out a dedicated U.S. platform in the near-term, but current build plans could support pairing manned and unmanned systems to partially fill the mission gap.

The Columbia class is the largest American submarine ever built. The Navy should study how to modify its common missile compartment to deploy cargo and fuel variants of unmanned underwater vehicles. These vehicles, loaded with critical supplies ranging from fuel and food to ammunition, could rendezvous with small rubber boats at predetermined waypoints and times, or even be modified to beach and relaunch on high tide. The UUVs could be stealthily launched from a submerged submarine at a great distance from the destination of the resupply, thus limiting the threat of detection and the level of risk to the delivery platform.

Current production, testing, and fielding of the ballistic-missile Columbia-class variant must first be completed for the sake of ensuring the United States’ nuclear deterrent capability. However, unmanned vehicle development and testing for logistical applications should be prioritized. Lessons learned from delivering less complex, inert payloads will likely reduce the time and cost to develop advanced versions, including intelligence-gathering and electronic-warfare suites.

The cost to modify class drawings and expand purchase contracts might seem high, but it is crucial to consider. As events continue to prove, even vastly superior militaries cannot win wars without capable, reliable, and survivable logistics to keep them fueled, fed, and armed.

Author

Michael Knickerbocker is a Surface Warfare Officer in the United States and has previously written about national security issues involving sustainment for The Hill, The National Interest, The Defense Post, and others. The opinions reflected here are his own and do not represent the official policy of the Department of Defense or the Department of the Navy. X: @saltystrategist