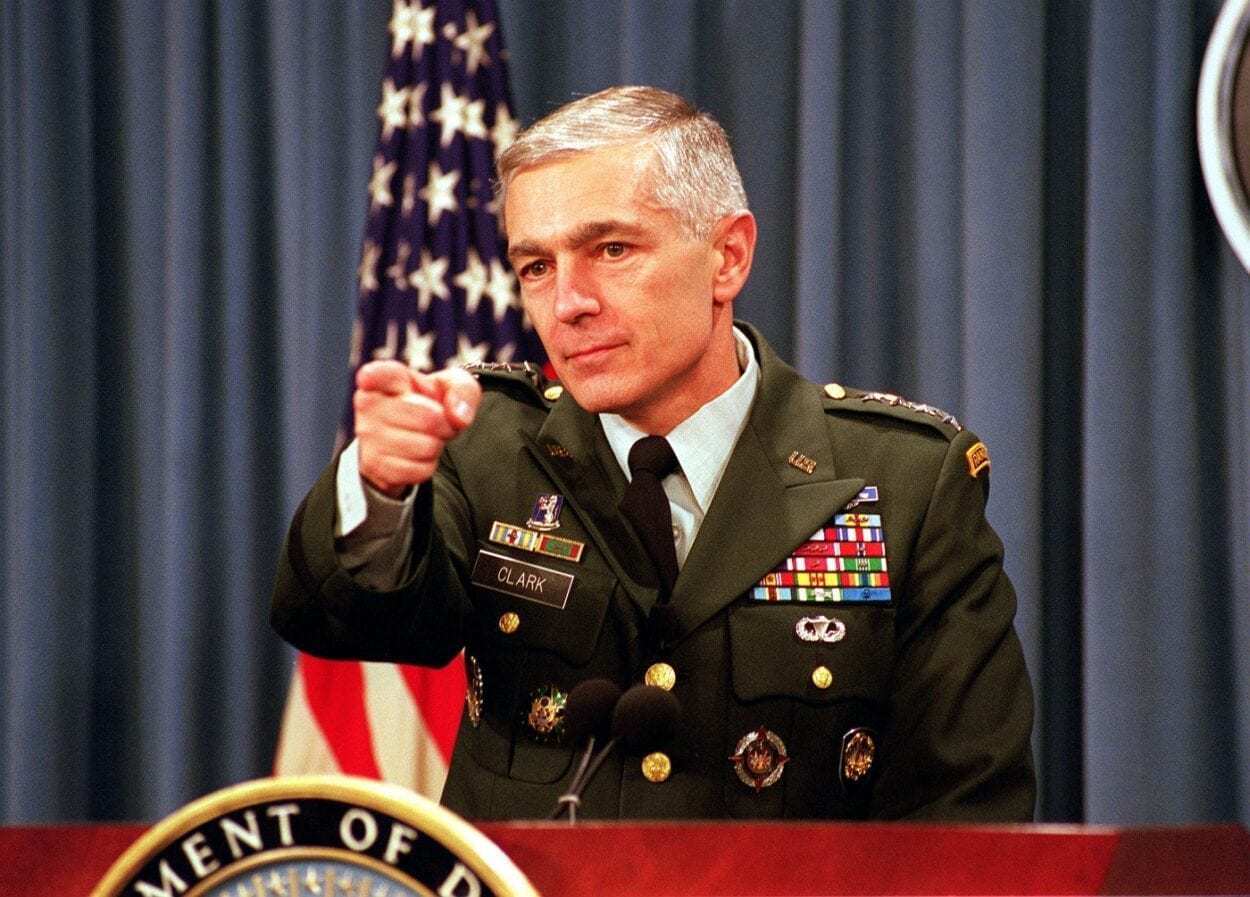

I had a chance to speak with Wesley Clark, former Supreme Allied Commander Europe who led the NATO response to Serbian aggression against Kosovo. Here are his responses below, edited slightly for clarity:

The situation in Belarus is surely disconcerting, to say the least. There is always the potential for Russian intervention to ensure its sphere of influence in an important former Soviet state. Let’s say that doesn’t happen and an opposition does take power, what should U.S. policy be going forward? Is this a case for NATO membership, for example?

In the unlikely event Lukashenko leaves, the US and the EU should offer humanitarian, economic, and various legal and political assistance through organizations like the National Endowment for Democracy. An offer of NATO membership would be both premature and destabilizing. Most likely, Russia is already intervening to regain control, and the more probable outcome is Russia’s absorption of Belarus, either through binding institutional arrangements or some legal mechanism at the state level.

Speaking of Russia, how should a Biden Administration, were the former Vice President to win, take on Moscow? Oddly, while Trump has talked about warmer relations with Russia and sometimes tried to cozy up to Putin, at the same time, he has imposed some tough sanctions during various times of tensions. What is your view?

President Biden should seek to engage Russia diplomatically and encourage Russia to reset its relations with the West. Crimea and Ukraine will remain sticking points, as well as Russian interference in the US elections. However, President Biden should seek to strengthen diplomatic engagement, find areas of common interest, like strategic arms control, and seek to persuade Mr. Putin that he will be more secure if he calls off his adversarial approach to the West and the United States. Sanctions could be relaxed in return for specific Russian actions in Ukraine and elsewhere.

Finally, going back to World War II, the United States made the centerpiece of its national security strategy to turn former enemies such as Japan, Italy, and then West Germany into strong, stable nations that were firmly part of the West. When the USSR and its allies lost the Cold War, while they did not lose a hot war where thankfully millions of people did not perish, it does not seem like the same effort or strategy was embraced.

Do you think the problems we have with Moscow and some of its former satellites comes from a failure to embrace that same strategy? Or, was Russia and the former USSR a different situation entirely?

Although the Soviet Union collapsed and ‘lost” the Cold War, the Soviet intelligence agencies had already begun a two-pronged plan to place Soviet funds in the West, where they were safe, could earn returns and could be used to sustain Russian intelligence activities and take over the democratic transition in Russia through training intelligence gents to stand for and win seats in elections.

Both strategies were successful. A former Soviet KGB officer has maintained power – and his anti-Western orientation – for over 20 years.

What happened? We never actually “defeated” the Soviet Union, in the way we defeated our World War II adversaries; after the Cold War ended, we lacked access to Soviet records, personnel, and institutions to be able to reform them and reshape public opinion there. The United States and our allies were simply ill-prepared to understand, appreciate, and manage this challenge as it emerged, even though some were warning of the problem at the time. Now we have strong adversarial elements deeply embedded in Western institutions, and especially in our economies, that use our own values of open societies and rule of law to spread propaganda, disinformation, and gain corrupting influence over political activities in many Western countries, including the United States.