Sports imitates life. And vice versa.

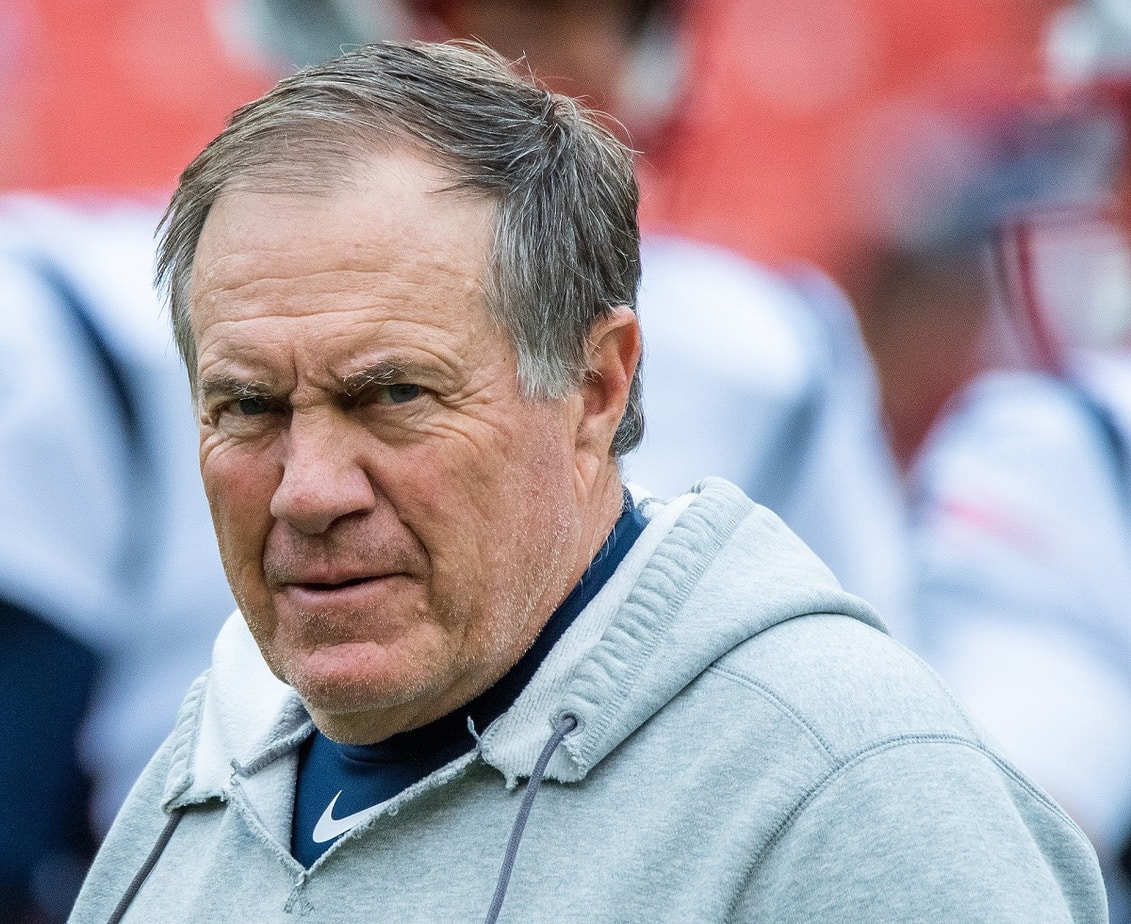

Over at Sports Illustrated last week, Connor Orr put forth an intriguing analysis of “Why the Patriots’ Open Quarterback Spot Is Still the NFL’s Most Interesting.” Such stories are catnip for loyal New England fans, especially those of us who can almost espy Foxboro from our front porches. Orr joins a debate that has roiled fandom since quarterback Tom Brady departed Foxboro after a triumphal two-decade run that culminated in nine Super Bowl appearances, six of them victories. Brady won a seventh Super Bowl with Tampa Bay last month. His instant success with different coaches and teammates set fans to wondering whether he or Coach Bill Belichick—both of whom have been anointed the GOAT, or greatest of all time—was mainly responsible for the Patriots dynasty.

Does the answer matter? Well, yes. And more than bragging rights is at stake.

Tom Brady vs. Bill Belichick is a fun mental jiujitsu match, but it is more than an idle debate to carry on in your favorite taproom. Whether the franchise prospers in the future could depend on the debate’s outcome, and in concrete ways. The Patriots are without a marquee quarterback after bringing in former Auburn Heisman Trophy winner and Carolina Panthers MVP quarterback Cam Newton on a one-year contract. The coaching staff has apparently adjudged the Newton experiment a failure, and is pondering where to find a new superstar QB.

Yet Belichick could find it hard to attract top talent to New England—including a new franchise quarterback—if potential recruits conclude that the Patriots’ dominance resulted not from stellar coaching but from Brady’s ability to lift the team to excellence. Such a verdict from the sports world is far from inconceivable. After all, Belichick has posted a decidedly mediocre record in his coaching stints without Brady, losing more than he has won. If the conventional wisdom concludes that Belichick has been more lucky than good, the Patriots could come to look like a lackluster cause in the eyes of prospective recruits. Players would shy away from coming to Foxboro—and seek football glory elsewhere.

The Brady v. Belichick controversy, then, could besmirch the Patriots’ image as a winner along with Belichick’s reputation as a coaching whiz. In turn, the team’s ability to recruit elite players would suffer. And without elite players, it’s an open question whether even a virtuoso coach can execute his game plans. Perversely, then, the team could stagnate on the field if an abstract debate among sports fans and experts goes against Belichick. Bottom line, subjective impressions of power and weakness—whether fair and accurate or not—have direct implications for a competitor’s future success. Reputation is everything.

This is true in the NFL; it’s also true in power politics.

Strategic competition in the politico-military realm resembles strategic competition on the gridiron in striking ways. Coaches want to project an aura of prowess to attract talent, whip up enthusiasm among the fan base, and intimidate opponents. Martial competitors want to project an image of prowess to woo allies and partners to their cause while cowing opponents. To compete successfully, that is, you should try to cast yourself as the likely winner and your opponent as the likely loser should there be a contest of arms (or football acumen). It’s about molding opinion in your favor and thus about managing your image.

None of this would have been lost on General George S. Patton. Patton hit on a basic fact about human nature in 1944, when he told the Third Army that people love a winner and despise a loser. That being the case, it is natural to side with a likely victor in hopes of savoring the sweet fruits of triumph. Who sides with a likely loser, and knowingly shares the bitter fruits of defeat? Curating an image of competence, resolve, and material excellence primes a contender to thrive in peacetime crises as well as on the field of battle in wartime.

This is what strategist Edward Luttwak means when he refers to “armed suasion” or “naval suasion.” Designing and fielding implements of war and wielding them expertly makes an impression on audiences able to influence the outcome of a competition. And again, impressions count. Constituents back home take pride in their armed forces and lend them all-important political support come election time or when a crisis looms. Allies take heart, knowing commitments to their security interests will be kept. A pall descends on councils in hostile states, discouraging mischief-making.

In martial affairs as in sports, the impressions formed by target audiences need not be fair or accurate; they are influential all the same. Whoever most audiences believe would have won a real battle “wins” the virtual battle for perceptions. Think about it. Most foreign and domestic observers are not specialists in military hardware, tactics, or operations. They are ill-qualified to judge, say, one warship’s fighting power against another’s. As Luttwak notes, Soviet vessels often prevailed against their American counterparts in peacetime showdowns during the late Cold War—even though they were technologically backward by Western standards.

A port view of the Soviet nuclear-powered guided-missile cruiser KIROV at anchor. In the background is a Soviet Krivak I-class guided-missile frigate.

Why? Because they exuded sex appeal! U.S. Navy warships’ weapons were secreted in magazines deep with their hulls, or in vertical launch silos embedded in their decks. The visually impressive stuff remained out of view. In contrast to nondescript American ships, hulking Soviet ships were festooned with enormous missile launchers, guns, and all manner of antennae and sensors. They looked formidable—and the look of a weapon system counts for a great deal when trying to awe nonspecialists.

So the Soviet Navy might outmatch the U.S. Navy in the battle for perceptions even though it would have been outgunned in actual combat. Moscow could reap unearned political dividends from its large and outwardly intimidating but backward fleet—overawing friends and antagonists of the Soviet empire. As a result, the political competition between Eastern and Western navies was a close-run thing—even though the West came out ahead by strictly military measures of battle strength and competence.

False impressions, then, may beget baneful consequences. The political and psychological dimensions of strategic competition are worth bearing in mind when preparing for the next contest—whether in Foxboro or at the Pentagon. Success could depend on the intangibles.

James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College. The views voiced here are his alone.