President Joe Biden’s first major speech on national security at the virtually-held Munich Security Conference will not be remembered in the same historical annals as Obama’s Cairo address or Reagan’s Evil Empire speech. As expected, Biden sought to draw a distinct line between himself and his predecessor, repeatedly assuring allies that the U.S. is committed to the transatlantic relationship and portraying the last four years as an exception to longstanding American policies. The rest of the speech gave an overview of various geopolitical challenges from China and the Iranian nuclear program to pandemic prevention and climate change, with high-level positioning points about each.

It was a fairly nonchalant 18 minutes, underscored by no significant discussion or decisions on more pressing issues like force drawdown in Afghanistan or U.S. troop levels in Europe. But within the rather generic tropes about world order and the dangers of tyranny was a dismaying level of idealism about America’s role in the world and our ability to influence the developments in foreign states.

The words “democracy”, “democracies”, or “democratic” were used 14 times in the Munich speech, as Biden detailed a global landscape that pits democratic nations against the rising tide of authoritarianism that seeks to sow discord against world harmony. This is a familiar dynamic that presidents of both parties have sought to depict since the end of the Cold War, from Saddam Hussain invading Kuwait to Russian interference in foreign elections. It is also a simplistic and narrow way of looking at international affairs, better suited for the campaign stump or news punditry than serious diplomatic discussions.

Such rhetoric becomes worrisome and even dangerous when American leaders begin talking about protecting or spreading democracy abroad. In his speech, Biden states:

“We have to protect — we have to protect for space for innovation, for intellectual property, and the creative genius that thrives with the free exchange of ideas in open, democratic societies. We have to ensure that the benefits of growth are shared broadly and equitably, not just by a few.” [bold added]

This type of statement is warming, but what are we actually signing ourselves up for when we say “we have to protect … we have to ensure” in the context of a speech on foreign policy and national security? Will we enact sanctions to ensure that economic growth is shared broadly, or wage war to protect intellectual property?

Safeguarding the world for the spread of democracy was a key argument from the George W. Bush administration when launching the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. While such aspirations may seem noble when discussing at an embassy cocktail hour, it was much more difficult in practice. The United States and other democratic governments have certainly proven the benefits of democracy for fostering freedom and human flourishing, but we forget that these victories were hard-won and the result of centuries of upheaval and cultural and civic development – and the system is still imperfect.

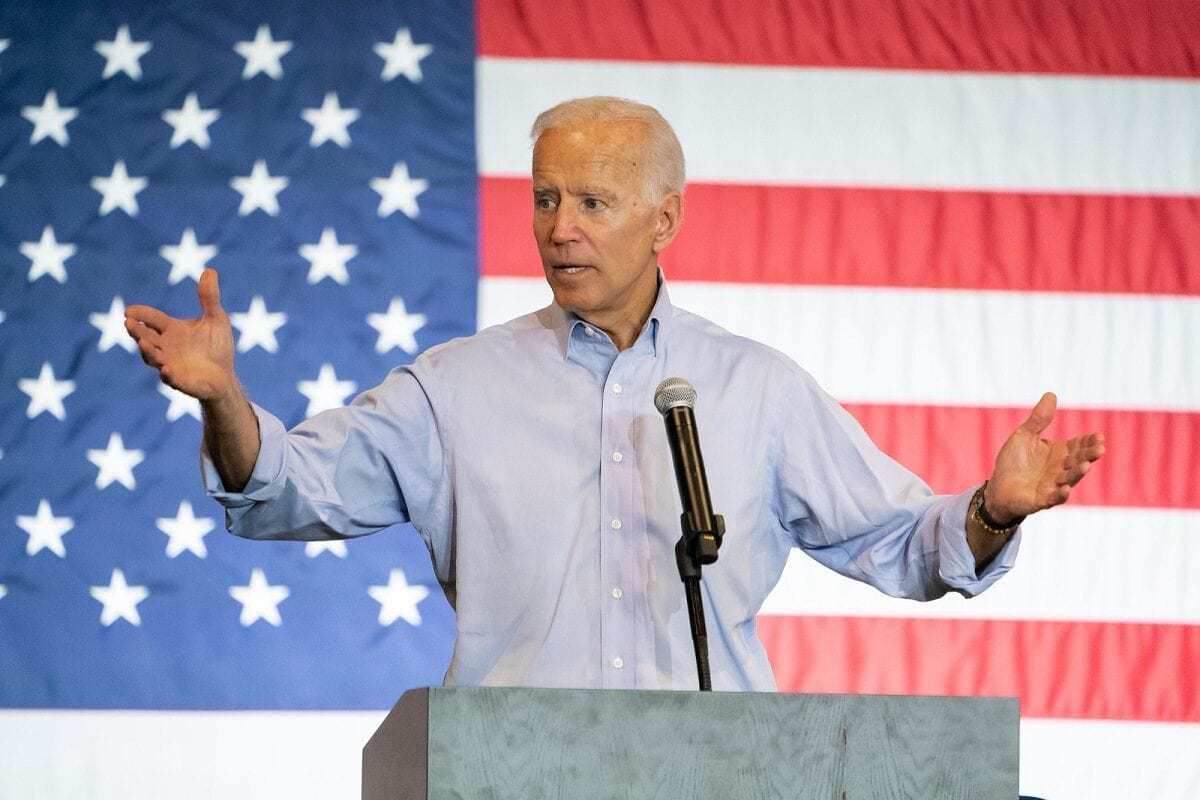

Town Hall at International Longshoreman’s Association Hall – Charleston, SC – July 7, 2019.

Expecting pre-packaged democratic governance to quickly take root in cultures where those enabling civil structures do not exist was a shortsighted and historically unfounded concept. Nor was it necessary to protect our own democracy.

When Biden did discuss ending the war in Afghanistan – something that is strongly supported in the United States – he qualified it by saying “We remain committed to ensuring that Afghanistan never again provides a base for terrorist attacks against the United States and our partners and our interests.” Such a qualification, much like the concept of “protecting democracy”, could mean anything in practice. Afghanistan is a country of nearly 40 million people who have been at war for decades, some of whom harbor deep anger towards the U.S. A commitment that no one operating out of that country will ever be able to threaten us, our allies, or our interests again would keep us there in perpetuity.

And like many of these idealistic theories about maintaining the world order and forever defeating all forms of evil, they have not proven to be attainable nor necessary for protecting our vital national interests. On the contrary, they have kept us mired in hostilities chasing elusive dreams about developing good governance and introduced us into conflicts in places like Libya and Syria, where our push to topple authoritarians created new opportunities for extremism and proliferated humanitarian disasters.

The Biden administration is still in its first weeks and has time to set a better course for American national security, based on a realistic assessment of our security needs and what U.S. citizens require of their government – not what we think the world requires from us.

Robert Moore is a public policy advisor for Defense Priorities. He previously worked for nearly a decade on Capitol Hill, most recently as the lead staffer for Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) on the Senate Armed Services Committee.