Everyone makes mistakes. While it’s always useful to learn from our errors, it’s always better to learn from the mistakes of others – or to benefit from observing what they did right. As President Joe Biden contemplates whether to stick with the May 1st withdrawal date from Afghanistan or to press for a new deal, learning lessons from how the Soviets withdrew from their disastrous Afghan adventure could save America a lot of grief.

Drawing parallels from historical examples to current events is always dicey because there are typically significant differences between the two situations. But in the case of Afghanistan, there are enough similarities between the experiences of the 10-year Soviet experience and America’s of today that some of Moscow’s lessons learned can be adapted to our benefit.

The Beginning

The Soviets went to war in Afghanistan because they believed the rise of an unfriendly government in Kabul was a threat to their southern flank. In a decisive meeting of the Politburo in Moscow following a March 1979 revolt in the province of Herat, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko told his colleagues they may have to consider the application of “extreme measures” in Afghanistan. In a now-declassified top-secret document, Gromyko said that “under no circumstances can we lose Afghanistan.”

Later that year Premier Leonid Brezhnev agreed on the need to fight and on Christmas Day 1979 Soviet troops began the invasion. Coming as it did one month after the U.S. embassy in Iran was attacked, just before the critically important SALT II Agreement was to come before the Senate for ratification, and during a particularly acrimonious time between the U.S. and USSR, Moscow considered the war necessary. They believed it would be a short, decisive military incursion.

Soviet troops in Afghanistan. Highlands near Kabul, 1986. Officer of 40 Army (OKSVA) conducts fire training with units arrived from the Soviet Union, bombarding them with 30-millimeter automatic grenade launcher AGS-17 “Flame” (so-called “trial run” to get used to combat). Units are in shelters.

It didn’t take long to realize how badly they were mistaken.

In March 1985, after five inconclusive years of war, Mikhail Gorbachev became the Soviet Premier. His initial attitudes towards the Afghan war were unchanged from his predecessor. Shortly after becoming premier, he assigned one of the USSR’s most famous generals at the time, General Mikhail Zaitsev, to try and shake up the war and win it.

Acknowledgment of Military Futility

After conducting an assessment of the war, however, Zaitsev reported to Gorbechev that it would take another quarter-million soldiers – on top of the 100,000 then deployed – to win the war. Gorbechev nevertheless gave him one year to try and win the war without any additional troops.

Predictably, Zaitsev did not succeed, and after another year of costly stalemate, Gorbechev finally accepted the war could never be won militarily. At a June 26, 1985, Politburo meeting, he announced that the time had come and “we have to get out of (Afghanistan).” The process of withdrawal, he said, will be complete “within two to three years.”

As the Soviets discovered, getting out of a war is far more difficult than getting into one. The Soviets had to coordinate military, economic, and diplomatic activities to end the conflict and then coordinate a successful withdrawal of their combat troops. It also had to be done in a way that gave fig-leaf cover for the USSR to end the war without looking like it had lost – all of which takes a lot of time. Gorbechev, however, felt the planning and preparation were taking too long.

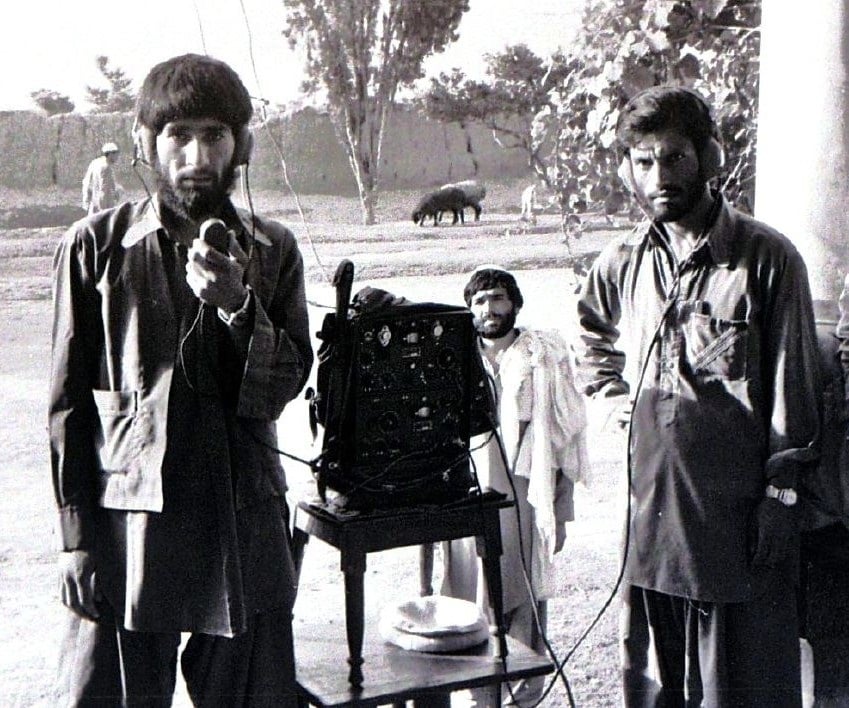

A mujahideen fighter in Kunar uses a communications receiver.

“At this point,” he told a November 1986 meeting of the Politburo, “we have been fighting in Afghanistan for six years. If we do not change our approaches, we will fight there for another 20 to 30 years. We must end this in short order.” It took another painful year and a half, but the breakthrough finally happened in April 1988 with the signing of the Geneva Accords. This agreement was formally between the government in Kabul and Pakistan, with the U.S. and USSR as “guarantors.”

It provided that the Soviet Army would execute a phased withdrawal beginning on 15 May 1988 and would be completely out of the country by 15 February 1989. The Washington Post echoed the fears of many at the time when it pondered the response of the Soviet government, “if, as is widely expected, the Moscow-dominated Kabul regime collapses within a few months and Islamic fundamentalists take over another nation on Russia’s southern border.” What no one in the West knew at the time, however, was that Moscow had already taken steps to mitigate against that outcome.

Laying the Groundwork

In an analysis of the Soviet withdrawal published in 2007, Historian Lester Grau wrote during the negotiating phase of the Agreement, the Soviets installed a new leader in Afghanistan, Mohammad Najibullah. “Moscow gave him two years to get his country in order,” Grau wrote.

Najibullah, recognizing that his regime – and life – depended on being ready when the withdrawal was complete, began working feverishly to produce a stable government and security apparatus. In an attempt to get buy-in from multiple constituencies, he produced a new constitution that included a multi-party political system – unheard of in communist countries – and an Islamic legal system. But as is always the case in war, things didn’t smoothly follow the withdrawal timeline.

The Mujahedeen – who were not a party to the Geneva Accords nor part of any withdrawal considerations – tried to take advantage as the Soviets began their withdrawal and tried to take over several major cities from the Afghan government forces. The attempts failed, but it alarmed Najibullah, who requested 20,000 Soviet troops remain to safeguard the regime in Kabul. Moscow refused the military request but did agree to provide other, critical assistance.

As Lester Grau wrote, even after the withdrawal, the Soviet government agreed to continue supporting the Najibullah government with, “a 600-truck convoy [that ran] weekly to the Soviet Union for resupply. The Soviet Union maintained its air bridge, flying in cargos as diverse as flour and SCUD missiles.”

Despite the insurgents’ efforts to defeat Najibullah’s government during and after the withdrawal, the Afghan forces repelled them all. With each success, the confidence and capability of the armed forces grew and the strength of the insurgents waned. Despite the Washington Posts’ fears in 1988 and popular belief today, the Afghan government did not fall because the Soviet military withdrew but only came after the Soviet economic and agricultural support disappeared overnight with the dissolution of the USSR in late 1991.

Lessons to Learn

There are several aspects of the Soviet war in Afghanistan that are significantly different from the U.S. experience. Unlike the United States, the USSR waged a fairly large-scale conventional battle against an insurgent army, often including significant use of tanks, artillery, and aerial bombardment against large enemy formations.

The Soviets made little attempt to win “hearts and minds” of the civilians, often destroying entire villages as retribution for the attack on their troops. Another big difference is that Moscow was under significant pressure from its civil population – even in the oppressive communist regime – over the increasing casualty count suffered by its troops. Total Soviet casualties exceeded 14,000 killed and over 53,000 wounded in 10 years of war while the U.S. suffered more than 2,400 killed and 20,000 wounded in twice the number of years fighting.

But there are enough similarities that make studying their withdrawal a valuable tool for Washington policymakers, especially as the Biden Administration grapples with whether to adhere to the May 1st withdrawal date negotiated by the Trump Administration.

Both the USSR and United States fought against a radical Islamic insurgency and for a civilian government, each country largely selected. Whether heavy-handed or using surgical strikes, both powers were unable to defeat the insurgents. The mujahedeen and Taliban were both fully committed, to the death, to continue fighting no matter how many years it took or how heavy were their casualties.

The first lesson we can learn from the Soviet experience is perhaps the greatest: a sober recognition that the war cannot be won. For all the criticism of the USSR – and there was much to justifiably criticize – both the political and military leadership accurately concluded that the war could not be won in a timeframe and at a cost that was acceptable. No leader wants to be the one accused of having finally “lost” a war, but the best thing Biden could do for America is to honestly acknowledge that the war cannot be won militarily and allow the current withdrawal schedule to stand.

Second, just like there were many fears in 1989 that the USSR-backed government would fall as soon as Soviet troops withdrew, there are many today who make similar claims about the U.S.-backed regime in Kabul falling if the last American troops leave.

That is not an unsubstantiated concern; it could happen. But it is also just as likely that the Ghani government – as the Najibullah regime before him – will take actions and make needed compromises necessary to ensure success post-American withdrawal. Having open-ended American military support perversely gives Afghan leaders incentive against making the hard compromises necessary to end the war. Our withdrawal places the Afghan government’s survival in their own hands – and there is every reason to believe they’ll do whatever is necessary to successfully negotiate with the Taliban.

Lastly, Moscow’s fear in 1979 that their security would be at risk if a non-communist government arose in Kabul was shown to be unsubstantiated. Russia’s military and internal security forces have successfully dealt with the terrorist threat which may exist on their southern border. Likewise, the fear in America that a U.S. withdrawal will result in “a new 9/11” is equally unfounded. Our security is underwritten by our powerful ability to identify and strike direct threats to America regardless of where in the world the threat may emerge.

Conclusion

Had President Obama learned from the Soviet experience and brought all our troops home at the end of 2016 like he promised, we would have saved countless lives and hundreds of billions dollars. Had Trump ended the war on his watch as he said many times he would do, we would have saved the lives and limbs of yet more troops and additional scores of billions. Now it’s Biden’s turn to make the choice.

As the evidence of the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan shows, our country’s security will not be imperiled, even if the worst-case happens and Kabul’s government falls. With a solid post-withdrawal plan, there is reason to hope the government will not fall. Yet all evidence screams that if we fail yet again to withdraw this time, the war will continue its predictable, pointless, and futile march to perpetual oblivion.

Daniel L. Davis is a former Lt. Col. in the U.S. Army who deployed into combat zones four times and the author of “The Eleventh Hour in 2020 America.” The views shared in this article are those of the author alone and do not represent any group. Follow him @DanielLDavis1.