The collapse of the Afghan government and Afghan National Security Forces once US and NATO military support ended has been graphic and rapid.

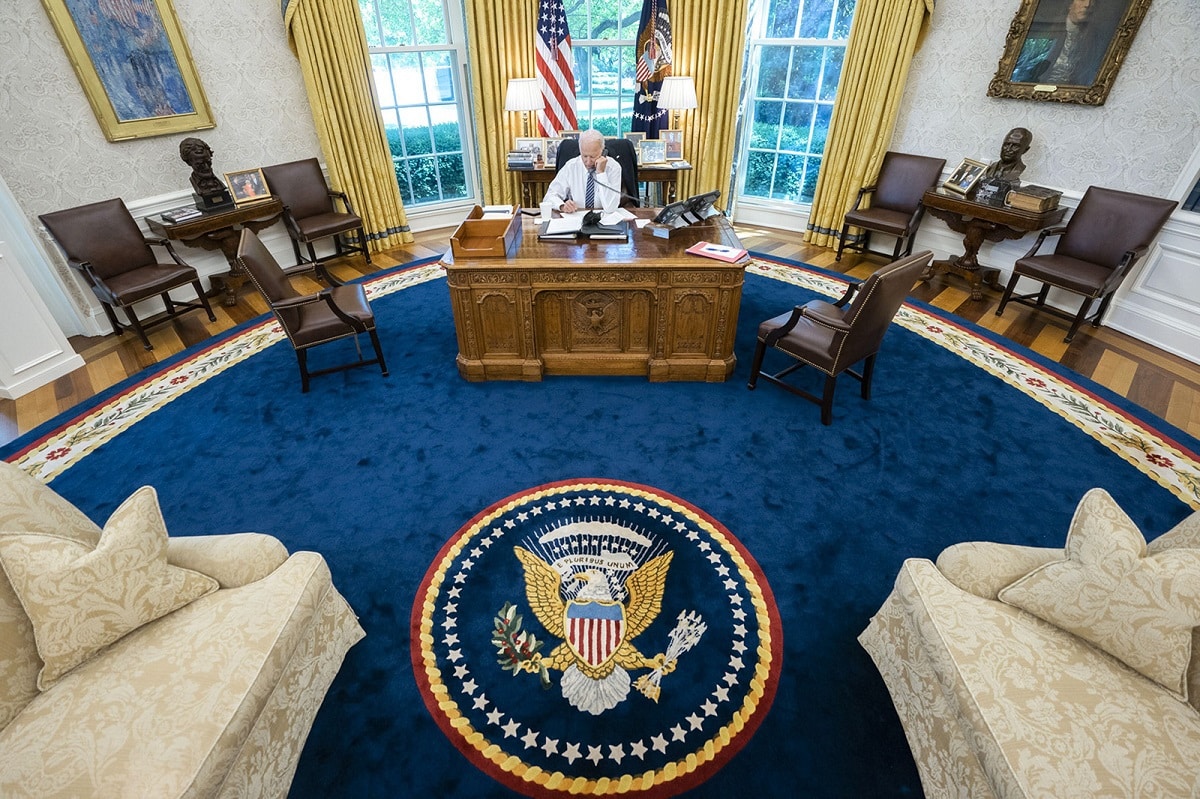

There are many analyses about the folly of US President Joe Biden’s administration and the blindness of intelligence agencies that seem not have to predicted this outcome. But it’s much more likely that it was foreseen and understood; just not that it would happen so fast.

The ANSF were built to operate within the framework of coalition support that was available for most of the past decade—high levels of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance information coupled with rapid close air support and contractor support for logistics and maintenance.

Once that framework was removed, the ANSF no longer had a method of fighting the Taliban that worked, and were without the assured backing of US and NATO power. It’s not surprising their will to fight evaporated quickly. That, in parallel with the Taliban’s opportunistically rapid advances, led us to where we are: with a Taliban regime in Kabul.

The speed of events has been a shock, but their direction was entirely foreseen—and most likely understood by not just the Biden administration and NATO members but by other coalition members too, including the Australian government. Even if there was a hope that this wouldn’t happen and that somehow the Afghan authorities would hold on and retain control of the capital and other centres, hope is not a method.

What does all this tell us? Biden meant what he said when he announced both the Afghanistan and Iraq withdrawals, so we should expect that he also meant what he said when he committed America to facing the systemic challenge from China, focused on the Indo-Pacific.

Biden was not for turning on Afghanistan, even as events accelerated to the rapid collapse.

If the Taliban advance on the capital had shocked him, he had the option of reversing Taliban momentum by backing the Afghan government and its forces. That could have been done by returning US air, logistics and intelligence support to the abandoned Bagram base near Kabul and so stiffening ANSF capability and resolve to retain control of Kabul—with some 4.6 million of Afghanistan’s 37 million people. But he didn’t, and other US partners, NATO members and Australia seem not to have united around such an urgent response to events on the ground.

American public reaction overall has been muted and hasn’t followed the line of reports in major media criticising Biden’s decision. The general sentiment has been to support Biden’s decision despite events in Kabul. Republicans have in the main simply said they would have managed the withdrawal better.

There will be predictable and ugly follow-on consequences, for the Afghan people, for Afghanistan’s neighbours and, quite likely, for the wider world. Taliban human rights abuses are not new, but the scope for these, including against members of the Afghan government and its agencies, is large. Their scale is likely to be too.

No one should expect restraint from a triumphant Taliban. Early assistance and positive engagement with the new rulers of Afghanistan, despite their record of atrocities and in the midst of their acts against opponents, will be easier for governments whose own conduct shows this matters less to them.

What happens from here should to an extent be laid at the door of the US, NATO partners and Australia for how we ended our military presence, and be shared by enablers and supporters of the Taliban over the last 20 years.

Engagement with the Taliban will be on their terms, with core behaviour not moderated by external exhortations or resolutions. The US and NATO withdrawal leaves no vacuum in Afghanistan for others to fill—Afghanistan is a dense patchwork of domestic power and interests that any external forces will find as confronting now as through its history.

Any partners of Afghanistan’s new rulers will engage with eyes wide open about the complicity this brings them in how the Taliban rule the people of Afghanistan. There are likely to be few ‘win–win’ outcomes for the Afghan people.

Outflows of refugees are expected, but they will face a more difficult environment than ever, with countries’ border controls considerably tighter than in pre-Covid times and local populations more willing to see these controls enforced.

Australia and other coalition partners must meet our obligations to Afghans and their families who worked closely with us over two decades, with much faster processing. The pace of this work needs to at least match the pace of its environment—a systemic issue for our government and agencies that extends well beyond Afghanistan.

The export of global terror may be the one thing the Taliban understand would cross a threshold for response even now. They’re unlikely to want to repeat the lessons of 9/11 and decades of war. We shouldn’t leave this to chance, though, so resources must still be focused on assessment and warning of attack planning from within Afghanistan.

Beyond Afghanistan, the US and NATO withdrawal only makes sense if it’s the first shoe to drop in a two-step move.

We now need to see not only that Biden had the resolve to keep to the Afghanistan withdrawal as the nasty human consequences it involved became palpable, but that he and his administration now apply that same resolve to the systemic challenge Xi Jinping’s China provides to the US and open societies globally, with a focus on the Indo-Pacific.

And here, the US has to be joined by partners demonstrating equal resolve.

The stakes for Australia as a key US ally in the Indo-Pacific are high, and forthcoming major events in the US–Australia alliance will test our joint resolve—a meeting of Australian and US defence and foreign ministers in the annual AUSMIN talks, and a possible meeting between Biden and Prime Minister Scott Morrison, maybe timed to coincide with the next Quad leaders’ meeting.

These meetings take on particular importance now, and they must do much more than turn the handle on routine alliance management.

It’s in the US’s interests to re-establish momentum in Biden’s foreign and defence policy and to follow through on words about reasserting American economic, strategic and technological power through and with its allies and partners in Europe and the Indo-Pacific.

Commitments to a greater US military presence in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, enabled by new Australian investments in naval and other facilities supporting our own and US forces in Australia’s north and west, are achievable, tangible demonstrations of resolve and power. As will be acceleration of technological and military–industrial cooperation that adds to US and Australian deterrent power, like coproduction of advanced missiles in Australia.

Resolve to take large strategic decisions and to live with their consequences is a rare commodity.

We’re experiencing a reckoning with Afghanistan and two decades of decision-making now. What we do on the abiding strategic challenge of China under Xi can either store up future reckonings or set a path to face the challenges with resolve and partnership.

Afghanistan is a reminder that the US is a ruthless power and ally with a stark calculation of its interests. This is a lesson for allies and adversaries equally.

For Australia, our alliance has long been what we tell ourselves routinely—a deep one based on shared interests and values. Those interests are deepening in the world we see emerging.

A key message from the US is that it is much more likely to support allies who are capable. It will help those who help themselves—and who can make useful contributions to US interests.

A demanding and ruthless US is maybe not what America’s adversaries expected from a Biden administration. Whether America’s partners and allies can work with the implications of that we’ll begin to see at AUSMIN and in other leadership forums over the rest of 2021.

Michael Shoebridge is director of ASPI’s defence, strategy and national security program.