Coming Soon: A Stealth Drone Bomber for the US Air Force? – The US Air Force is looking to develop a drone stealth bomber that could complement capabilities offered by America’s forthcoming B-21 Raider. This development speaks to the apparent success of efforts to pair the Air Force’s forthcoming air superiority fighter with drone wingmen in the Next Generation Air Dominance, or NGAD, program.

During a keynote speech delivered at the Air Force Association’s 2022 Warfare Symposium three weeks ago, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall revealed that the United States is exploring the idea of an uncrewed stealth bomber platform that could fly missions ahead of the optionally-crewed B-21 Raider to expand upon America’s deep penetration strike capabilities in hotly contested airspace. This new bomber platform would be expected to have “comparable range” to that of the new globe-spanning bomber, with payload capabilities to be determined in large part by price point.

The Air Force’s new drone stealth bomber may be in the $300-million price range

Based on Kendall’s statements, this drone stealth bomber effort is looking to field something far more capable than an attritable (semi-disposable) support aircraft.

“We’re looking for [uncrewed] systems that cost nominally on the order of at least half as much as the manned systems that we’re talking about for both NGAD and for [the] B-21,” Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall said.

At a price point of around half the cost of a B-21 Raider, that would place this new aircraft in very expensive company. According to Aviation Week, Northrop Grumman’s B-21 was originally projected to carry a per-unit cost of $511 million, which when adjusted for inflation marks about $640 million. That would mean the Air Force’s new drone stealth bomber may cost anywhere from $250 to $320 million per aircraft—roughly the equivalent of buying four brand new F-35As.

“The nominal ‘one-half’ is sort of an estimate of what we should shoot to achieve as a minimum at this point. I’d love it to be lower,” Kendall added.

While Kendall qualified this bomber concept as “more speculative” than other secretive programs like Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD), he explained that the Air Force is currently in the “concept definition” stage of planning for it—in other words, they’re hashing out exactly what capabilities this platform will need and how best to go about fielding them.

In comments made after his remarks, Kendall spoke to this process, explaining that ongoing debate centers around which capabilities found in the B-21 can be omitted from a drone wingman and which capabilities are must-haves.

It will be able to carry at least a 4,000-pound payload with a combat radius of 1,500 miles (but these numbers or likely very low)

An unclassified Request for Information the Air Force has released to industry partners calls for this new drone stealth bomber to have at least a 4,000-pound payload capacity and a combat radius of 1,500 miles, but as Aviation Week’s Steve Trimble has pointed out, it seems likely this aircraft will need to be able to match the B-21’s range in order to serve its purpose as a means of support on long-duration missions.

This drone stealth bomber effort, Kendall explained, is a classified project that will only see acknowledgment in official discourse but will otherwise operate with very few details revealed to the public. Despite that, he anticipates funding for this new aircraft will begin with the branch’s 2024 budget proposal.

It may build off of previous drone efforts from Boeing or Northrop Grumman

As Steve Trimble pointed out on Twitter, the stated requirements for this new aircraft follow closely with Northrop Grumman’s X-47C effort from more than a decade ago—which aimed to field a stealth drone about the size of the B-2 with a 20,000-pound payload capacity, building off the successes of the X-47A and B. That’s not to say that the X-47C will be adopted as the B-21 Raider’s new bomber wingman, but it does suggest that Northrop Grumman—the primary contractor on the B-21 itself—is well-positioned to develop this new platform as well.

Boeing’s X-45D, which was once set to compete with the X-47C for an operational contract, could also fit the bill, however. The X-45D was expected to boast a 20,000-pound payload capacity as well, with public statements at the time touting the ability to deliver as many as 80 250-pound bombs to targets deep inside contested airspace.

It will be stealthier than the F-35 or F-22

Both of these aircraft leveraged a variation on the flying-wing design now found in the B-2 Spirit and the forthcoming B-21 Raider, and it seems all but certain that regardless of who builds it, the Air Force’s new drone stealth bomber will follow suit.

This design, while not lending itself to extreme maneuverability, is harder to detect on UHF and VHF band radar systems than stealth fighter designs like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter and F-22 Raptor. These fighters are extremely difficult to target using high-frequency radars like those used by modern air defense systems, but because of their need for things like vertical tail sections, they remain fairly easy to detect using lower-frequency radar bands. While not good for securing a weapons lock, these low-frequency radars can be effective early-warning systems and can be used in conjunction with other systems to try to target stealth aircraft.

Stealth fighters are effectively designed to operate in airspace where the enemy expects or even knows they’re there—but stealth bombers like the B-2 Spirit, B-21 Raider, and this forthcoming drone bomber are designed to avoid being detected at all. The B-21 is also expected to leverage an onboard electronic warfare suite to further bolster its ability to tiptoe past these increasingly prevalent VHF-band systems. It seems likely this electronic warfare capability is among the functions Air Force personnel are currently debating about adding to its stealth drone bomber wingman.

It will leverage tech from Skyborg and DARPA’s ACE program

In his remarks, Kendall highlighted how this new drone stealth bomber will leverage technologies developed within both Boeing’s Skyborg effort and DARPA’s recent ACE, or Air Combat Evolution, program to couple the crewed B-21 with its drone wingmen. And further, he seemed to suggest that the NGAD program’s efforts to do the same are both further along and rather promising.

“I’m quite convinced [as] to the cost-effectiveness of a mix of crewed and uncrewed aircraft for the NGAD family of systems,” Kendall told Aviation Week.

“I’m hopeful that we’ll get a similar answer for the longer-range B-21 family, but we want to do the work to make sure that’s true.”

Skyborg is an “autonomous aircraft teaming architecture” meant to pair crewed aircraft with a constellation of uncrewed drone platforms for support. These autonomous wingmen will take their cues from the human pilot and serve as an extension of the aircraft’s combat capabilities, flying ahead to serve as extended sensor nodes, engaging targets with onboard munitions, and potentially even sacrificing themselves to protect the crewed aircraft.

“Military pilots receive key information about their surroundings when teamed aircraft with integrated autonomy detect potential air and ground threats, determine threat proximity, analyze imminent danger, and identify suitable options for striking or evading enemy aircraft.” –Air Force Research Laboratory

The ACE program, headed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), is similarly all about pairing human operators with computers, but inside their own aircraft. The Air Combat Evolution effort aims to place an advanced artificial intelligence in the cockpit with pilots to minimize cognitive load, sort of like a highly capable co-pilot. In a way, ACE is the logical extension of existing trends in fighter technology, which have long aimed to automate more and more of the aircraft’s operation to allow the pilot to focus on the fight at hand.

“ACE creates a hierarchical framework for autonomy in which higher-level cognitive functions (e.g., developing an overall engagement strategy, selecting and prioritizing targets, determining best weapon or effect, etc.) may be performed by a human, while lower-level functions (i.e., details of aircraft maneuver and engagement tactics) is left to the autonomous system.” “Air Combat Evolution (ACE)” by Lt. Col. Ryan Hefron, DARPA

In 2020, the ACE program pitted a highly trained human F-16 pilot against an AI pilot created by Heron Systems in a virtual dogfight using only guns. The AI defeated the human an impressive five bouts in a row without ever taking a single hit, prompting many to claim AI may be ready to replace human operators in American fighters. However, the competition was conducted under strictly controlled circumstances inside a virtual environment. Despite the fanfare that the victory secured for Heron’s AI, DARPA’s primary intent was to demonstrate the capability of AI as a viable addition to crewed fighter platforms.

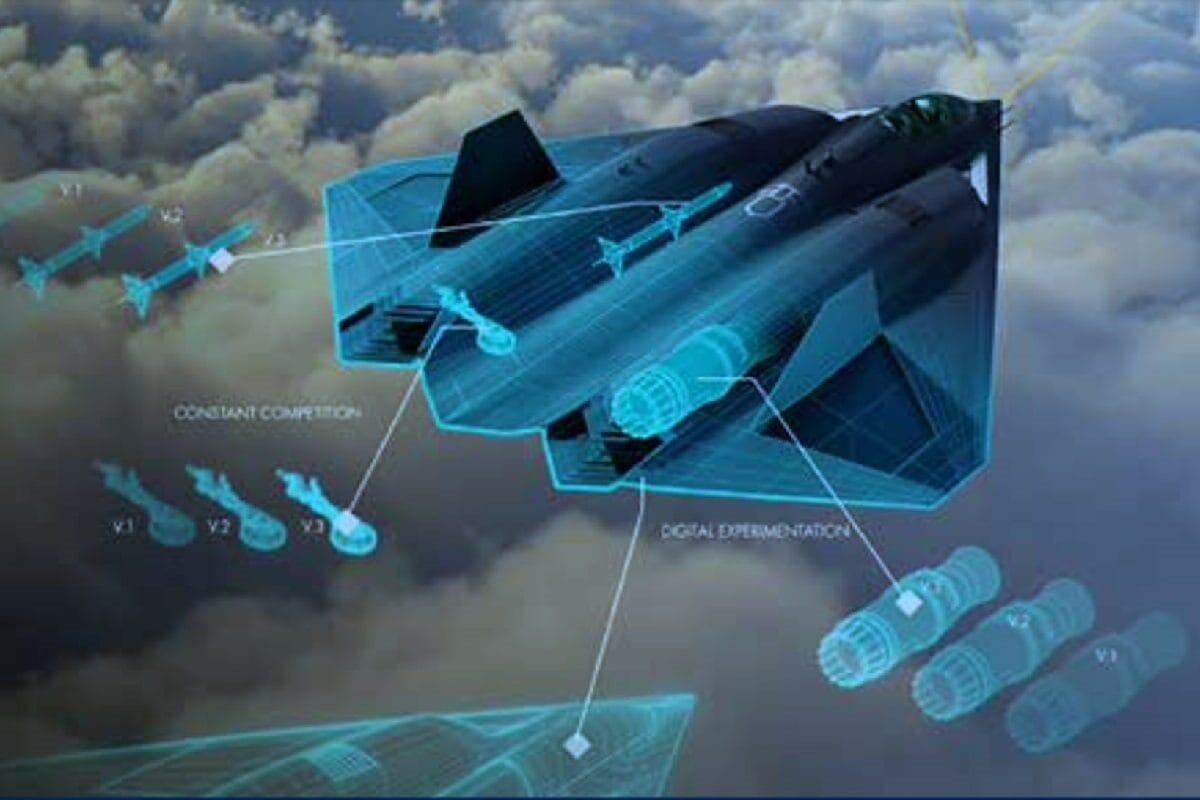

This drone stealth bomber effort suggests NGAD development is going well

While the Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance program (aimed at fielding a new air superiority fighter) remains shrouded in secrecy, Kendall re-emphasized that it isn’t one new aircraft being designed and built, but rather a “system of systems.” NGAD will include a crewed aircraft with a pilot on board, alongside a variety of lower-cost uncrewed platforms like those envisioned by Skyborg. This would allow for a significant increase in payload capacity, sensor reach, survivability, as well as variety in mission-specific payloads.

For instance, if multiple drone platforms are developed to fly in conjunction with NGAD, different platforms can specialize in different applications and then be paired with an aircraft prior to a mission, rather than having to swap out pods or even internal hardware on the fighter itself. NGAD fighters could be paired with drone platforms that specialize in electronic warfare, ground attack, air superiority, reconnaissance, or a combination of skills, all without adding weight or removing ordnance from the fighter itself.

NGAD Artist Rendering (Note: Not a US Government Image).

US Air Force image of possible NGAD Concept. Image Credit: US Air Force.

Interestingly, Kendall’s statements about price points, particularly regarding the B-21’s drone stealth bomber wingman, suggest the NGAD’s own drone accomplices may be far more expensive (and capable) than originally thought. These drones are expected to be “attritable,” meaning cheap enough to stomach their loss in a fight. Previous Air Force statements have suggested the “attritable” price range tends to fall between $2 and $20 million—which may sound expensive, but a single Patriot missile used in American air defense systems actually rings in at around $3 million. A single AGM-158C Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM) costs the Air Force nearly $4 million.

Kendall’s remarks seem to redefine the Air Force’s take on “attritable,” now allowing for a much greater overall cost as long as a human operator isn’t put in harm’s way. In effect, Kendall seems to suggest that, while the Air Force would never sacrifice a human pilot to accomplish a mission, the Pentagon’s definition of attritable likely falls on a sliding scale, weighing capability and cost against opportunity and risk.

“They can also be attritable or even sacrificed if doing so confers a major operational advantage—something we would never do with a crewed platform,” Kendall explained.

A drone stealth bomber would help tip the scales of power in the Pacific

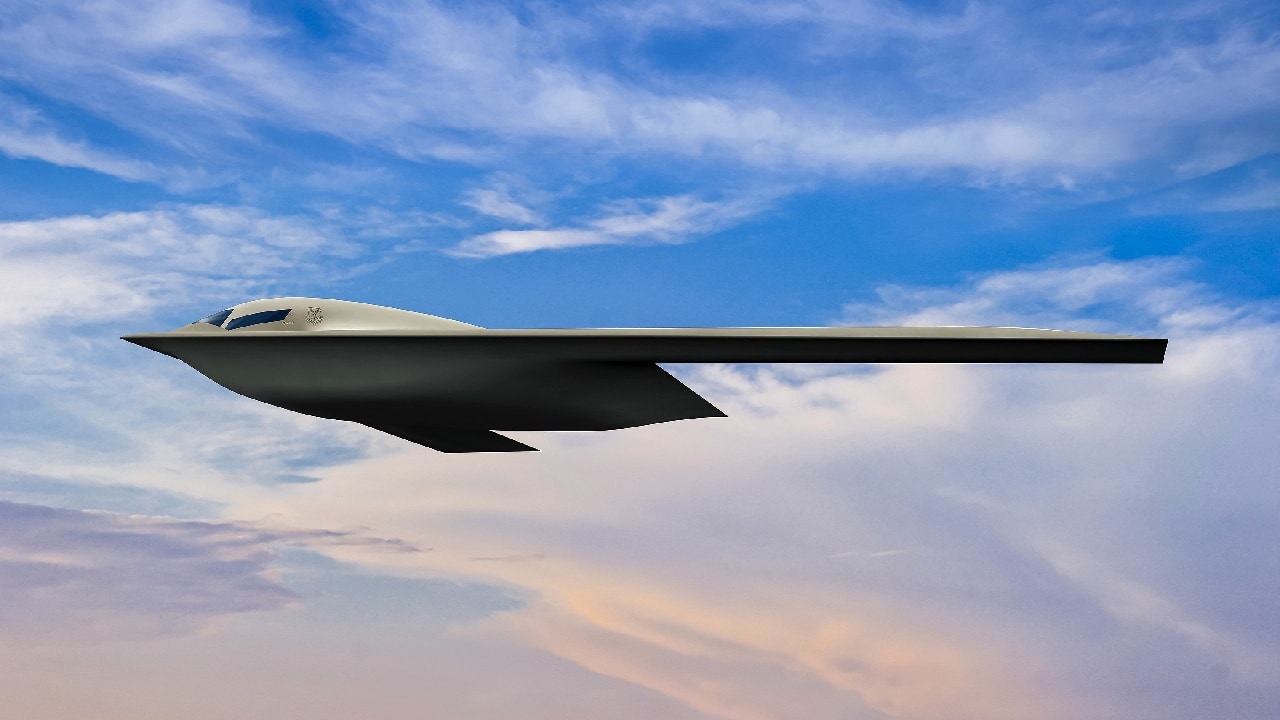

A clear design successor to Northrop’s previous and highly successful B-2 Spirit, the B-21 Raider is expected to be smaller than its predecessor, with a payload capability expected to sit at around 30,000 pounds (10,000 less than the B-2), while offering broader capabilities and improved survivability in a 21st-century battlespace. The Air Force intends to procure at least 100 B-21s, which will replace its standing fleets of both B-2 Spirits and B-1B Lancer supersonic heavy payload bombers.

As we’ve discussed here at Sandboxx News before, the B-21 Raider may be the key to America’s ability to counter China’s A2/AD (anti-access and area denial) strategy in the Pacific. China’s arsenal of anti-ship missiles, particularly long-range hypersonic weapons like the DF-ZF boost-glide vehicle, have created an “area denial bubble” extending more than a thousand miles from Chinese shores that American carriers can’t penetrate without being at risk of being sunk. This is a huge challenge for the U.S. Navy and American foreign policy, as the Navy’s carrier-capable fighters lack the range to engage Chinese targets from that far out. In other words, neither the Block III Super Hornet nor the F-35C Joint Strike Fighter could reach China without giving China the opportunity to sink one of America’s supercarriers.

B-21 Raider Stealth Bomber. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

As such, the globe-spanning B-21 Raider would almost certainly play a vital role in the initial days of conflict with China if one were to break out. Stealth bombers would fly thousands of miles, refueling in mid-air as needed, to engage anti-ship weapon systems on Chinese shores to reduce the threat posed to America’s Nimitz and Ford-class carriers. But this effort wouldn’t be without substantial risk.

Stealth is not a singular technology that renders an aircraft “invisible” to radar, but rather an overlapping combination of technologies, production methodologies and combat tactics meant to delay detection and limit targeting. In other words, stealth aircraft are not as safe in contested airspace as they may seem thanks to decades of combat over nations without any appreciable air defenses to speak of. A combination of radar and infrared tracking, (tracking the heat produced by a stealth jet’s engines) could, for instance, bring a stealth aircraft down. And that’s not the only way.

New anti-stealth radar systems like bi-static radars and multi-static radars, which separate the radar transmitter from the receiver, may reduce the effectiveness of radar-reflecting designs, and because radar-absorbent materials don’t fare well under the high heat associated with supersonic flight, adding a great deal of speed to deep-penetration bombers (like a stealthy B-1B, for instance) simply isn’t a feasible way to improve survivability if targeted. With a per-unit cost creeping up toward the $1 billion dollar mark, the Air Force can’t afford to lose many stealth bombers in the early days of a large conflict.

F-35 stealth fighter. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

And that’s where a substantially cheaper drone stealth bomber that can fly ahead of the B-21 Raider could offer a huge strategic value. Raider crews could use these uncrewed bombers to target anti-ship weapons that are too well defended to risk engaging themselves, or they could engage air defense systems to allow for a safer route to the objective. Of course, at half the cost of a B-21, we’re still talking about a drone stealth bomber that costs as much as three or more F-35s, but again, the F-35 very likely couldn’t reach these targets to begin with… and these new drone stealth bomber could.

Drones won’t make stealth bomber pilots history. They’ll make them the future.

It seems all but certain that uncrewed aircraft, both in combat and out, are the future of aviation, but it’s important to note that the Air Force has no plans to do away with human pilots. Despite the popular idea that AI is already advanced enough to take over for human operators in complex combat environments, most tests of these systems remain relegated to controlled virtual environments and established operational guidelines. As any fighter or bomber pilot who’s flown operational missions will tell you, there are no such things as controlled environments and mutually established operational guidelines in combat. In a real fight, the enemy gets a great deal of say in how things shake out.

While computers can withstand greater G forces than human operators, can process information more quickly and from a broader array of inputs, and can even respond to incoming threats faster than a human pilot, they still lack the nuanced decision-making processes we take for granted in our heads. That’s why, despite pop culture and social media trends so frequently pitting AI against human pilots, the Pentagon would much rather couple highly capable AI with highly capable human operators to create a best-of-both-worlds approach to air combat.

When asked if this new drone stealth bomber effort could lead to removing bomber pilots from the fold, Kendall didn’t make a clear assertion either way, highlighting that it’s important to explore other options while pointing out one of the crewed bomber’s most important strengths in a nuclear era.

“I don’t know. We’ve been doing bombers a long time. They’ve all been manned, and they’ve all been from the air. But that doesn’t mean you can’t do global strike from other means,” he said, but the “advantage of a manned bomber, though, is you can actually recall it, if you choose.”

Will AI eventually become so capable we can do away with humans on the battlefield altogether? It seems possible, but it almost certainly won’t be for decades to come. In the meantime, coupling the B-21 Raider with a drone stealth bomber that can support complex operations in a similar way to how Skyborg, ACE, and NGAD aim to change fighter air combat seems like a no-brainer, AI or otherwise.

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran who specializes in foreign policy and defense technology analysis. He holds a master’s degree in Communications from Southern New Hampshire University, as well as a bachelor’s degree in Corporate and Organizational Communications from Framingham State University. This first appeared in Sandboxx News.