Hypersonic weapons are all the rage these days. Between America, Russia, and China who has the advantage right now? Lockheed Martin and the US Air Force announced the successful test of an air-launched hypersonic missile on Tuesday, marking a notable shift from three previous failures from the same program. This is now the third successful US test of a hypersonic weapon since September.

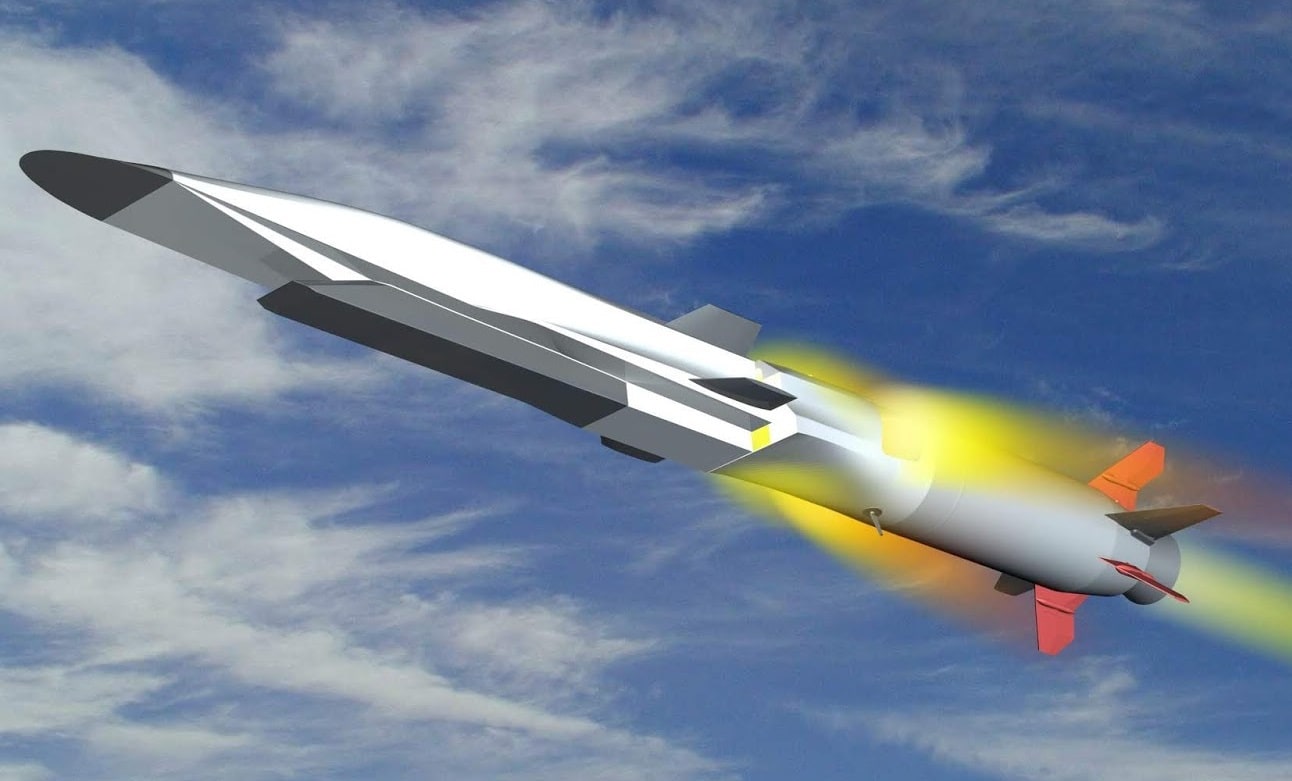

Lockheed Martin’s AGM-183A Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon, or ARRW, was launched from the wing of a B-52H Stratofortress off the coast of Southern California on May 14, per the Air Force release. Once launched, the weapon’s booster ignited, carrying ARRW to a higher altitude and hypersonic speeds for an “expected duration.”

“The test team made sure we executed this test flawlessly,” Lt. Col. Michael Jungquist, 419th FLTS commander and GPB CTF director, said in a statement.

“Our highly-skilled team made history on this first air-launched hypersonic weapon. We’re doing everything we can to get this game-changing weapon to the warfighter as soon as possible.”

ARRW is a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle, which is one of two types of modern hypersonic missiles. By definition, hypersonic weapons travel at speeds in excess of Mach 5, or around 3,838 miles per hour, but technically speaking, that speed isn’t particularly groundbreaking. Ballistic missiles and spacecraft have been traveling at hypersonic velocities for decades now. What makes modern hypersonic weapons special, is their ability to couple that speed with maneuverability.

The United States recently conducted two successful tests of the other form of modern hypersonic missiles, scramjet-powered cruise missiles, in September of last year and in March. Both Russia and China claim to have hypersonic boost-glide missiles in service, while no nation has managed to field a scramjet-powered cruise missile for operational service to date.

America is arguably lagging behind in hypersonic technology due to Russia and China’s in-service weapons, but the truth is, the hypersonic arms race as it’s often presented isn’t quite all it’s cracked up to be.

This is the first successful test of the ARRW hypersonic missile after three consecutive failures

The ARRW program saw a major setback earlier this year, when the Pentagon opted to do away with $161 million in procurement funds for the weapon in 2023 due to three consecutive failures in testing last year. The first failure came on April 5, 2021, when the weapon failed to separate from the B-52’s pylon. The second failure came just three months later, when ARRW successfully separated from the aircraft, but the booster motor failed to fire. Then, in December of 2021, the weapon once again failed to successfully separate from the B-52 carrying it.

Last month, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall made it clear that the hypersonic ARRW missile must prove it can perform in testing before it can move forward.

“The program has not been successful in research and development so far,” Kendall told the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense. “We want to see proof of success before we make the decision about commitment to production, so we’re going to wait and see.”

Now that ARRW has a successful test under its belt, it may finally be speeding its way toward operational service, but it’s certainly got some ground to cover first. According to the Air Force, ARRW will see more testing throughout 2022. If all goes well, we’ll likely see funding for procurement put back on the table for the branch’s 2024 budget proposal next year.

What does this mean for the hypersonic arms race between the US, Russia, and China?

As we’ve discussed in previous coverage, Russia’s KH-47M2 Kinhzal, which saw use twice in Ukraine last month, is not—technically speaking—a hypersonic weapon in the modern sense. Instead, it’s an air-launched ballistic missile that achieves hypersonic speeds in the same fashion all ballistic missiles do. Russia’s Avangard boost-glide vehicle, however, is a hypersonic nuclear-capable weapon deployed from Russian ICBMs like their latest (and largest-ever) RS-28 Sarmat. Likewise, China also has a boost-glide weapon in service in its DZ-ZF anti-ship platform that’s carried aloft by the DF-17 ballistic missile.

America’s inability to field a similar boost-glide vehicle to date has been presented in the media and by some politicians as a significant failure for America’s Department of Defense, but that’s not exactly an accurate portrayal of the nature of this arms race. Russia’s Avangard may be able to deliver nuclear payloads to American soil, but the nation’s long-dated ICBM arsenal could already do that.

China, to be clear, appears to have the lead in the testing and development of hypersonic weapons, thanks to a massive investment in hypersonic research and development infrastructure. However, despite Russia’s claims of operational weapons, the US may really be China’s primary competitor in this field. And with yet another success in the books, America may be closing the gap.

But there’s more to this discussion than simply fielding hypersonic weapons—it’s also important to consider what they’re intended to do.

While both Russia and China do have hypersonic weapons in service, their weapons are nuclear-capable and intended to serve as deterrents—or weapons that only need to see use in a near-peer conflict. Russia’s Avangard carries a two-megaton nuclear warhead, so they’ll never have to prove their weapon functions as advertised until a world-ending nuclear war has already begun. Likewise, China’s DF-ZF was designed to sink American aircraft carriers—another set of circumstances both the U.S. and China would prefer to avoid.

The prevailing wisdom within the Pentagon suggests that simply fielding a similar weapon to Avangard for the sake of winning headlines would offer the US very little strategic value. So, despite taking a beating in the press, the Pentagon is keeping its sight set squarely on adding new capabilities, rather than fielding weapons for the sake of optics. But, the decision to forgo nuclear hypersonic missiles actually creates some significant technical challenges.

The US is committed to only fielding non-nuclear hypersonic missiles (and that makes things tough)

The United States has committed to only developing conventionally-armed, or non-nuclear, hypersonic weapons that can be used as soon as they’re put into service for conflicts of all sorts, including counter-terror operations. The technical challenges of fielding a weapon that can be used in combat immediately, as opposed to one you can continue to perfect as it deters opponents, are quite different, as Lockheed Martin’s Dave Berganini, Vice President of hypersonic and strike systems at Lockheed Martin Missiles and Fire Control, told me earlier this year.

“We are in the midst of discovery on a first-of-its-kind weapon system that must work the first time it is called upon and operate safely for our warfighters,” Berganini said.

“The high-complexity and unique features of these systems, requires rigorous testing, learning from discoveries, and then maturing the technology to get it right the first time they may need to use it.”

The fact that these weapons are carrying conventional, rather than nuclear, warheads also creates significant challenges for targeting. According to the Congressional Research Service, a nuclear weapon can be up to 100 times less accurate than a conventionally armed one, thanks to the relative size of its blast radius. In other words, you can miss with a nuke, because the explosion is so big, it’ll find the target anyway.

The recent success of another Lockheed Martin hypersonic missile system in March, a scramjet that powered DARPA’S Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) demonstrator, may have even placed the United States in the lead when it comes to hypersonic cruise missiles, even if its focus on conventional warheads as slowed progress on boost-glide weapon designs.

What is a hypersonic boost-glide missile?

Hypersonic Boost Glide Vehicles (HGVs) are carried into the upper atmosphere via high-velocity boosters just like traditional ICBMs, but they’re often released at lower altitudes. Once released, these weapons rely on momentum and either control surfaces or chemical thrusters to maneuver during their high-speed descent.

Despite popular misconceptions, these weapons won’t necessarily reach their targets faster than traditional ballistic missiles, which follow more arcing (and predictable) ballistic flight paths. Because hypersonic boost-glide vehicles fly along a flatter trajectory and maneuver along the way, they can actually take longer to reach their target in some circumstances than a more straightforward ballistic missile warhead.

But it’s the ability to change course, rather than overall speed, that makes these weapons so difficult to defend against. Modern air defense systems rely on complex mathematical equations to predict where a missile will be so it can launch a kinetic interceptor (usually another missile) that will catch the inbound weapon at some point along its flight path. Because hypersonic boost-glide vehicles adjust course along the way, air defenses can’t reliably predict where to send an interceptor to stop them.

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran who specializes in foreign policy and defense technology analysis. He holds a master’s degree in Communications from Southern New Hampshire University, as well as a bachelor’s degree in Corporate and Organizational Communications from Framingham State University.