This week marks the eightieth anniversary of the Battle of Midway. That’s when, guided by imaginative intelligence work, remnants of the U.S. Navy fleet battered at Pearl Harbor ambushed the Kidō Butai, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s vaunted aircraft-carrier strike force, in the Central Pacific. American torpedo and dive-bombing assaults sent four Japanese fleet carriers plunging to Davy Jones’ locker by sundown on June 4, 1942, the day when the main fighting raged.

And Japanese naval air power was never the same.

But Midway resulted in more than downed planes and sunken ships. This was a battle with direct strategic repercussions, stalling Japan’s seemingly unstoppable campaign of conquest across the Indo-Pacific. Victory at sea prepared the way for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps to launch an amphibious counteroffensive in the Solomon Islands that August. The island-hopping campaign across the South Pacific would culminate in U.S. forces’ return to the Philippine Islands in late 1944.

The Battle of Midway is replete with valuable lessons, which is why historians and military folk still study it today. Here are two of my favorites. One, put your faith in commonsense leadership. Former U.S. Naval Academy and Naval War College professor Craig Symonds relates an instructive anecdote about Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, a surface warfare officer commanding Task Force 16, comprising carriers USS Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown and their escorts.

Accepted practice for the day had a flattop assemble its full aerial strike force overhead before sending the group on its way. And that’s prudent, isn’t it? Concentrating the air wing’s fighting power at the outset conformed to strategic logic, which advises commanders to amass superior combat power at the time and place of battle to overcome the enemy. By contrast, fragmenting a force tends to dilute its power. Keeping the group together assured fighter support for lumbering attack aircraft, which found it hard to defend themselves against fleet-of-foot Japanese fighters. And it reduced the frictions and dangers that come with scattering forces across the map while restricting radio communications among pilots to conceal their whereabouts.

Trouble is, planes waste fuel while orbiting overhead. The less fuel in their tanks, the shorter their striking range; and Spruance wanted to strike at extreme range, firing effectively first. So, despite the risks, he instructed his squadrons to proceed toward the Kidō Butai as soon as they got aloft. Swifter fighters would catch up with slower torpedo bombers and dive bombers enroute to their targets. If all went well, the air groups would mass combat power near the point of impact. That all did not go well for U.S. aviators on June 4 doesn’t obviate the wisdom of Spruance’s scheme.

Aristotle depicted common sense as the highest form of philosophy. And wisely so. It also ranks among the highest forms of leadership. When common sense collides with doctrine, go with common sense every time.

And two, manage risk. Pacific Fleet supreme commander Chester W. Nimitz essayed some commonsense risk management of his own. On the eve of battle Admiral Nimitz directed Spruance and fellow flag officer Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, embarked in Yorktown, to engage—or decline to engage—the foe according to the “principle of calculated risk.” He wanted them to interpret this principle “to mean the avoidance of exposure of your force to attack by superior enemy forces without good prospect of inflicting, as a result of such exposure, greater damage to the enemy.”

Nimitz trusted subordinate commanders to exercise their own judgment—and to refrain from fighting unless they expected to do worse to the enemy than the enemy did to them. The quest for disproportionate gain made sound tactics.

It’s worth noting that Nimitz could afford to be venturesome at Midway despite the depleted state of the post-Pearl Harbor Pacific Fleet. A simple actuarial formula defines risk as a product of multiplication of two variables, namely probability and consequences. Nimitz asked Spruance and Fletcher to gauge both variables, determining whether they had a good chance (probability) of meting out worse punishment than they suffered (consequences).

And what if they misjudged the probability of a favorable outcome, and suffered worse damage than they dished out? Well, Nimitz knew that a brand-new fleet was building back home pursuant to the Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940, and that that fleet would start arriving in the Pacific theater in mid-1943. If the worst befell Task Force 16 at Midway, the Pacific Fleet would have to make do until fresh hulls were displacing water. But replacements were on the way, win or lose. The immediate consequences of defeat could be frightful, in other words, but new shipbuilding reduced the longer-term consequences. Task Force 16 was not going to lose the war in an afternoon.

New construction, then, skewed the actuarial calculus toward risking the fleet. It’s easier to gamble with something precious when you have—or know for sure you will have—a spare.

The early phase of the Pacific War should inspire some soul-searching today. The fall of France to Nazi Germany spurred Congress and the Franklin Roosevelt administration to pass the Two-Ocean Navy Act, setting in motion a naval buildup long before America joined World War II. But neither the rise of China, nor the war for Ukraine, nor anything else has precipitated a similar surge in shipbuilding today. In fact, the Biden administration’s budget submission for fiscal 2023 proposes retiring 24 ships of war while constructing just 9 to replace them, for a net decline of 15 hulls in a single year. If the administration gets its way the inventory is set to shrink to 280 ships, well below the 355 mandated by U.S. law, not to mention the 500 or more crewed and uncrewed ships uniformed navy leaders say they need to cope with increasingly forbidding strategic circumstances.

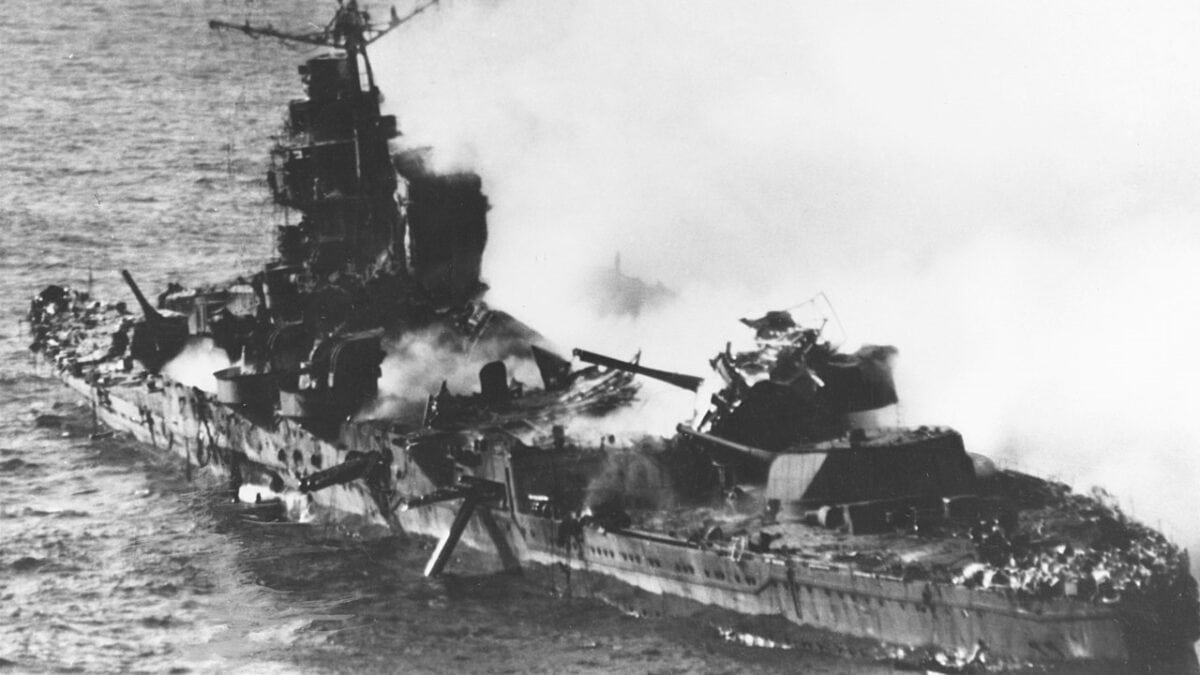

The Japanese heavy cruiser Mikuma, photographed from a USS Enterprise (CV-6) Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless during the afternoon of 6 June 1942, after she had been bombed by planes from Enterprise and USS Hornet (CV-8). Note her shattered midships structure, torpedo dangling from the after port side tubes and wreckage atop her number four 203 mm gun turret. The photo flight was led by Lt(jg) E.J. Kroeger, A-V(N), USNR, of Bombing Squadron 6 (VB-6) with photographer Mr. A.D. Brick of Fox Movietone News in a SBD-3 of VB-3 (“3-B-10”). Kroeger was accompanied by Lt.(jg) C.J. Dobson of Scouting Squadron 6 (VS-6) and photographer CP(PA) J.S. Mihalovitch in SBD “6-S-18”.

So again, the memory of Midway should give us pause. It’s doubtful a future Admiral Nimitz could give task-force commanders the same latitude his pre-battle directive bestowed on Admirals Spruance and Fletcher. Similar reserves of actual or latent combat power simply aren’t there, or in the making. Knowing that would bias commanders toward timid, conservative, risk-averse decisionmaking in naval warfare, a realm where enterprise is at a premium.

Official Washington should think twice before cutting back fleet numbers. Doing so would verge on passing a One-Ocean Navy Act of 2023 at a time when storm clouds are gathering.

A 1945 Contributing Editor, Dr. James Holmes holds the J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College and served on the faculty of the University of Georgia School of Public and International Affairs. A former U.S. Navy surface warfare officer, he was the last gunnery officer in history to fire a battleship’s big guns in anger, during the first Gulf War in 1991. He earned the Naval War College Foundation Award in 1994, signifying the top graduate in his class. His books include Red Star over the Pacific, an Atlantic Monthly Best Book of 2010 and a fixture on the Navy Professional Reading List. General James Mattis deems him “troublesome.” The views voiced here are his alone. Holmes also blogs at the Naval Diplomat.