The De Havilland Mosquito doesn’t have the name cred that other WWII fighters have for sure. That doesn’t mean that it didn’t make some serious history and help the allies attain victory: To most Westerners, the mosquito is a blood-sucking insect that’s merely an annoying pest. But in some parts of the world, the mosquito can be downright deadly, especially the Anopheles mosquito that’s responsible for spreading malaria. During WWII it was a different mosquito that struck fear. Nazi Germany ran afoul of a different species of Mosquito that was even more deadly and destructive to their plans for conquering Western Europe: the RAF’s De Havilland Mosquito fighter-bomber. As this article is being written on the same day that US-UK Friendship Day is being celebrated at Nationals Ballpark in Washington DC, let’s take a closer look at Britain’s mighty Mosquito.

Mosquito Movie Star

While not quite a household name to American movie audiences like aircraft such as the supersonic jet jock F-14 Tomcat and F/A-18 Hornet – thanks to the Top Gun film franchise – or even the RAF’s own single-engine Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane – thanks to the 1969 film The Battle of Britain starring Laurence Olivier and Robert Shaw – the twin-engine Mosquito still earned its fair share of cinematic stardom thanks to the 1964 film 633 Squadron starring the late great Cliff Robertson. There was also the far-less acclaimed 1969 film Mosquito Squadron starring David McCallum, best known as (1) Ilya Kuryakin in The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and (2) Dr. Donald “Ducky” Mallard in NCIS.

SPOILER ALERT: though 633 Squadron was no box office blockbuster by any stretch of the imagination, one YouTube poster – who obviously had an excess of free time on his/her hands – cleverly dubbed the dialogue from the Death Star attack scene of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope onto the climactic battle scene of the Mosquito movie.

The 633 Squadron movie was based on the 1956 novel of the same name by former RAF officer Frederick E. Smith, who in turn based his book on several real-life operations. And the Mosquito’s real-life exploits are every bit as impressive as the fictitious ones, if not more so.

De Havilland Mosquito – From Unwanted Pest to Hero

However, the warbird (yes, I’m using an avian metaphor for a plane named for an invertebrate) had some hurdles to overcome before attaining its legendary status. Indeed, De Havilland’s Mosquito started its service life much like its flying insect namesake, i.e. it was unwanted. As fellow 19FortyFive columnist Peter Suciu elaborates:

“All despite the fact that the British military didn’t really see the aircraft’s potential, and the Royal Air Force virtually ignored the aircraft at first … Even after a prototype had been ordered, the limited nature of the program – with just 50 aircraft – meant that it was removed entirely from plans three times after the Dunkirk evacuation. That could have been the end of the Mosquito, but like the pesky insect on a summer night, its supporters kept coming back to highlight its potential … The aircraft proved to be fast and agile, and quickly its detractors were silenced.”

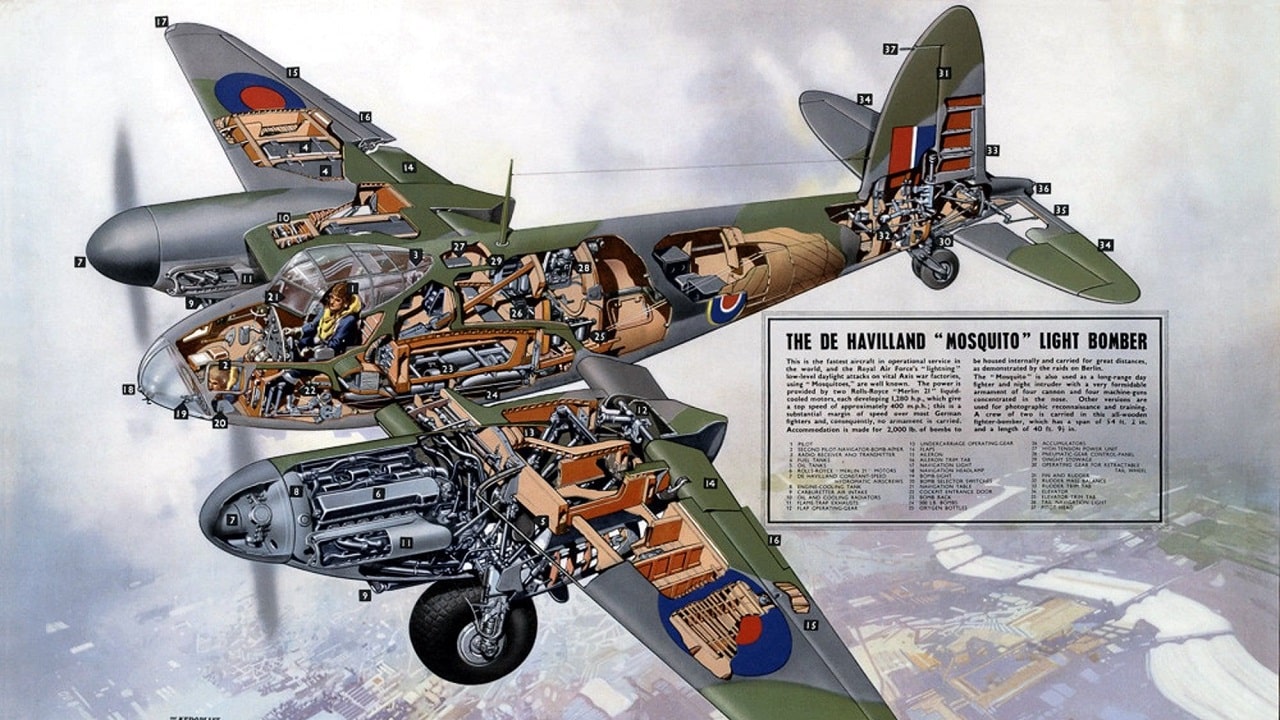

Indeed, when she finally officially entered service on November 15, 1941 – 10 days shy of the 1st anniversary of her maiden flight – the Mosquito turned out to be one of the fastest operational aircraft in the world, with a maximum speed of 415 mph (668 kph). The plane packed a powerful punch to go with her speed, to the tune of four .303 caliber (7.7mm) Browning machine guns, four 20mm Hispano cannons, and a 4,000 pound (1,800 kilograms) bomb load.

De Havilland Mosquito – The Swiss Army Knife of the RAF

The Mosquito was affectionately referred to as “Mossie” or the “Wooden Wonder,” the latter sobriquet due to its predominantly wood construction. The wooden emphasis was driven by the relative shortage of metal in Britain at the time, compared to the abundance of wood and skilled woodworkers. Developed originally as a two-seater, unarmed fast bomber, the aircraft proved itself to be amazingly versatile, ending up utilized as a fighter, fighter-bomber, night fighter, ground-attack aircraft, torpedo bomber, U-Boat hunter, transport, and even reconnaissance aircraft.

In the night-fighter role, the “Wooden Wonder” ended up claiming over 600 air-to-air kills against manned enemy aircraft as well as an additional 600 V-1 “buzz bomb” rockets. The first Axis warplane to fall victim to the night-fighter variant of “Mossie” was a Dornier Do-217 downed on May 30, 1942. Mossie could even hold her own against the Focke-Wulf FW 190, one of the most fearsome fighters in the Luftwaffe arsenal. In one particular incident, Mosquito pilots shot down five FW 190s in exchange for three losses.

However, as the saying goes, “Fighter pukes make movies. Bomber pilots make history!” (Just please don’t tell that to Tom Cruise! and Val Kilmer.) Sir Geoffrey de Havilland’s invention indeed attained its most significant accomplishment in the bomber role. The most famous of these bombing missions was Operation Jericho on 18 February 1944, whereupon nine Mosquitoes attacked the German-held prison at Amiens in a low-level strike that destroyed the outer and inner prison walls, quickly followed by the Guard House itself. This daring raid enabled the escape of 255 Allied POWs. Mosquitos would also score one of the great propaganda victories of WWII when one of their daylight attacks famously knocked out the main Berlin Broadcasting Station on the very day Herman Göring was giving a speech to celebrate the 10th Anniversary of the Nazis’ seizing of power.

The Mosquito ended the war with the fewest losses of any aircraft in RAF Bomber Command.

Where Are They Now?

A total of 7,781 “Wooden Wonders” were built from 1940 to 1950, and the craft was officially retired in 1963, Today, there are 30 surviving aircraft, with only four of these remarkable warbirds remaining airworthy, and eight more currently undergoing restoration. Static displays are spread through several museums in the UK, Canada, Norway, South Africa, Belgium, Australia, and the United States. The one I’ve personally experienced and can therefore highly recommend is the RAF Museum London, in the Hendon section of that grand old city.

Christian D. Orr is a former Air Force officer, Federal law enforcement officer, and private military contractor (with assignments worked in Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kosovo, Japan, Germany, and the Pentagon). Chris holds a B.A. in International Relations from the University of Southern California (USC) and an M.A. in Intelligence Studies (concentration in Terrorism Studies) from American Military University (AMU). He has also been published in The Daily Torch and The Journal of Intelligence and Cyber Security.