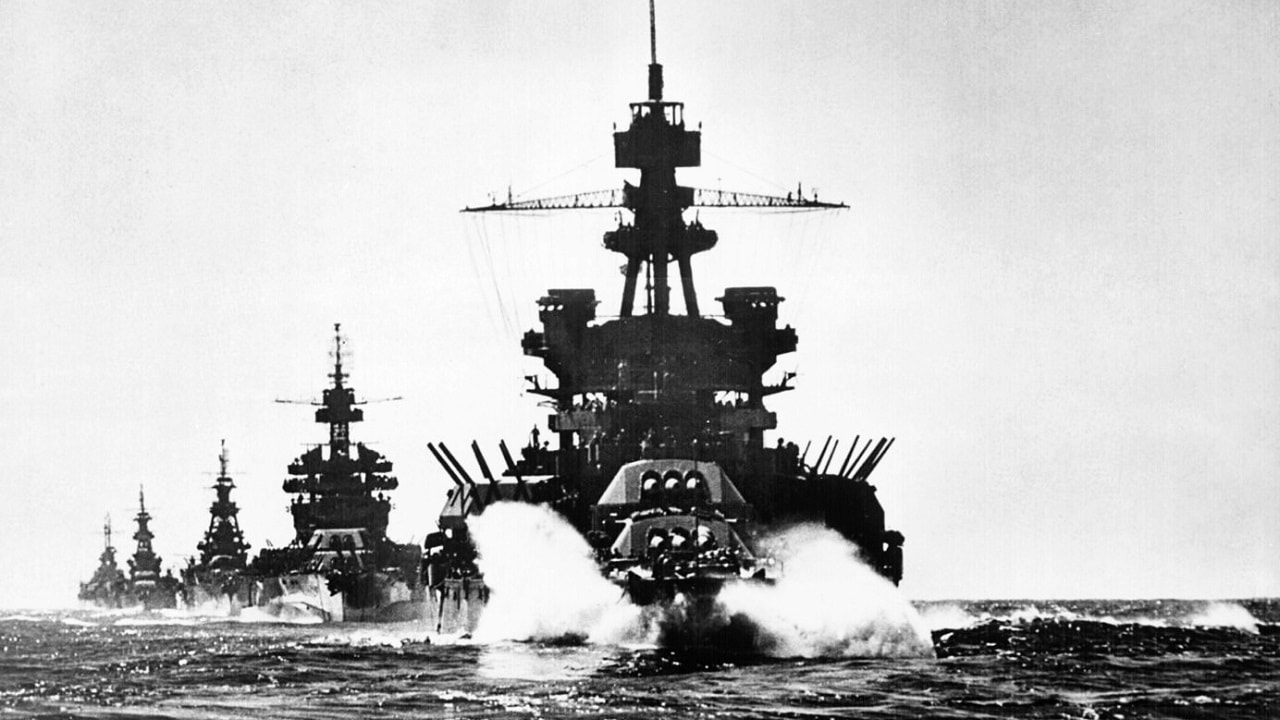

The U.S. military wanted to see what impact nuclear weapons would have on large naval armadas. So a massive fleet of World War II battleships and aircraft carriers was attacked with atomic bombs:

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the UK’s Royal Navy was the strongest maritime force in the world. However, by the end of that conflict, the power of the Royal Navy had been overtaken by the United States Navy, which was faced with a two-front war on the seas. The U.S. Navy actually proved more than ready for the challenge and the United States was able to produce a massive number of warships, yet, it should be remembered too that even at the outbreak of the war, the U.S. Navy was a considerable force.

In 1939, the U.S. Navy had 15 battleships, five aircraft carriers, 18 heavy cruisers, and 19 light cruisers. Those numbers were greatly increased by the time the United States entered the war in late 1941. Even as a new class of battleships – the Iowa-class – entered service, the focus shifted to aircraft carriers, of which 16 large flattops were built, along with dozens of smaller carriers.

When the fighting ended in 1945, the United States had more warships than any other power on the planet, and there was serious consideration regarding what to do with all those ships. For many of the old warships, they were used as targets – but for a very new kind of weapon.

Atomic Testing – Able and Baker

The United States military tested the first atomic bomb on July 16, 1945, at a site located 210 miles south of Los Alamos, New Mexico, on the plains of the Alamogordo Bombing Range, known as the Jornada del Muerto. The codename for the test was “Trinity.”

Just a year later, a joint U.S. Army-Navy task force staged the first atomic explosions since the bombing of Japan in August 1945. The test was codenamed Operation Crossroads – and it was conducted at the Bikini Atoll, a coral reef in the Marshall Islands, with a test goal to investigate the effect of nuclear weapons on warships.

A fleet of 95 target ships was assembled in the Bikini Lagoon, and the flotilla was hit with detonations of two “Fat Man” plutonium implosion-type nuclear weapons – the same that was dropped on the city of Nagasaki. Each had a yield of 23 kilotons of TNT.

The first test, conducted on July 1, 1946, was dubbed “Able” while the bomb was named “Gilda” – a reference to Rita Hayworth’s character from the 1946 film of the same name. Gilda was detonated 520 feet (158 meters) above the target fleet. However, as it missed its aim point by 2,130 feet (649 meters), it caused significantly less damage than initially expected.

The second test on July 25 of the same year was named “Baker,” while the bomb had been given the more colorful moniker “Helen of Bikini.” It was detonated 90 feet (27 meters) underwater, which resulted in radioactive sea spray that caused considerable contamination to the nearby test ships.

According to the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Evaluation Board, it was a serious and seemingly unexpected problem. The radioactive water that spewed from the lagoon “contaminated” the ships, which “became radioactive stoves, and would have burned all living things aboard with invisible and painless but deadly radiation.” It also meant that the task force personnel assigned to the salvage work had to deal with contamination. The original plan was to decontaminate the warships at the site, and that was only halted after many military and civilian personnel had been exposed to radioactive substances.

A third deep-water test that was to have been named “Charlie,” and scheduled for the summer of 1947, was canceled due to the Navy’s inability to decontaminate the target ships after the “Baker” test.

The Target Fleet

Among the warships that were employed in the Bikini Atoll Nuclear Target Fleet were two aircraft carriers and five battleships. These included the Lexington-class aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-32,), which survived the first blast but was damaged beyond repair in the second test; and the light aircraft carrier USS Independence (CVL-22), which survived both tests. Her radioactive hulk was later taken to Pearl Harbor and San Francisco for further tests and was finally scuttled off the coast of San Francisco, California.

The battle wagons used at the test site included USS Arkansas (BB-33), a Wyoming-class dreadnought battleship that was crushed by the first test, and the Japanese battleship HIJMS Nagato, which was heavily damaged in the July 25 bombing – sinking five days later.

In addition, USS Nevada (BB-36), the lead vessel of a World War I-era class of battleships and a survivor of Pearl Harbor, had endured both tests and was later towed back to Pearl Harbor for examination. She was later used as a gunnery target and finally was sunk by an aerial torpedo. Likewise, both USS New York (BB-34), the lead of her class, and the super-dreadnought battleship USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) survived the tests and were used for structural testing before finally being sunk.

Most of the other warships used in the testing, including a multitude of cruisers – including the German Navy’s Prinz Eugen – and a destroyer, also failed to be sunk in the testing. It was clear that the atomic bomb could easily level a city, but sinking a warship was another matter entirely. Of course, the radiation would still have likely killed the crew, yet contamination remained a very serious concern.

In fact, a 2016 study found that even so many years after the end of nuclear testing, radiation levels in some parts of Bikini Atoll remain at about six times the maximum safe limit.

A Senior Editor for 1945, Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers, and websites with over 3,000 published pieces over a twenty-year career in journalism. He regularly writes about military hardware, firearms history, cybersecurity, and international affairs. Peter is also a Contributing Writer for Forbes.