This spring, the Biden Administration acknowledged that it must re-write its National Security Strategy, which guides the country’s overall security strategy, no doubt in recognition that the U.S. grand strategy must be fundamentally revised. The revision is necessary given the invasion of Ukraine by Russia and a failed three-decade attempt to entice China to become a liberal democracy. That silence you continue to hear today is the United States’ new grand strategy, following the failure of the post-Cold War strategy of ‘engagement and enlargement’ toward Russia and China.

The Biden Administration’s first-ever National Defense Strategy (regardless of the classified specifics), sent to Congress in late March 2022, was likely short on both reform and big think. According to its unclassified Fact Sheet (no unclassified version has been published yet), it is purposefully noncommittal, once again calling China a ‘pacing threat’ and Russia an ‘acute’ and ‘near-term’ threat. Both seem understatements. Expect little change, therefore, to the updated, supposedly more thoughtful, and directive, National Security Strategy – whenever it appears.

The NDS, which guides U.S. defense policy, exists under and within a larger (and still current) post-Cold War U.S. grand strategy of ‘engagement.’ The policy has been advanced consciously and explicitly by the Clinton, Bush, and Obama Administrations (and somewhat ambiguously by the Trump Administration). A new National Security Strategy – or better, a new grand strategy – must now set out a more explicit whole government strategy, educated by our failed, twenty-eight-year attempt to moderate and liberalize the now totalitarian states of Russia and China.

The strategy of ‘engagement and enlargement’ was coined and advanced by the Clinton Administration in its 1994 National Security Strategy. It advocated strong defense; cooperative security; open foreign markets and global growth; and the promotion of democracy abroad to enhance security. It involved the major powers (particularly China) in a web of commercial, academic, social, and political relationships and institutions to dissuade them from committing aggression or changing the existing international order. Engagement was the strategy of ignoring the polities of these states in the belief that such involvement would encourage these states to accept and move toward liberal democracy.

Yet today, no one thinks that the current regimes in Russia or China will be seduced by further economic development into becoming representative liberal democracies, with checks and balances, competitive political parties, free speech, and limited government.

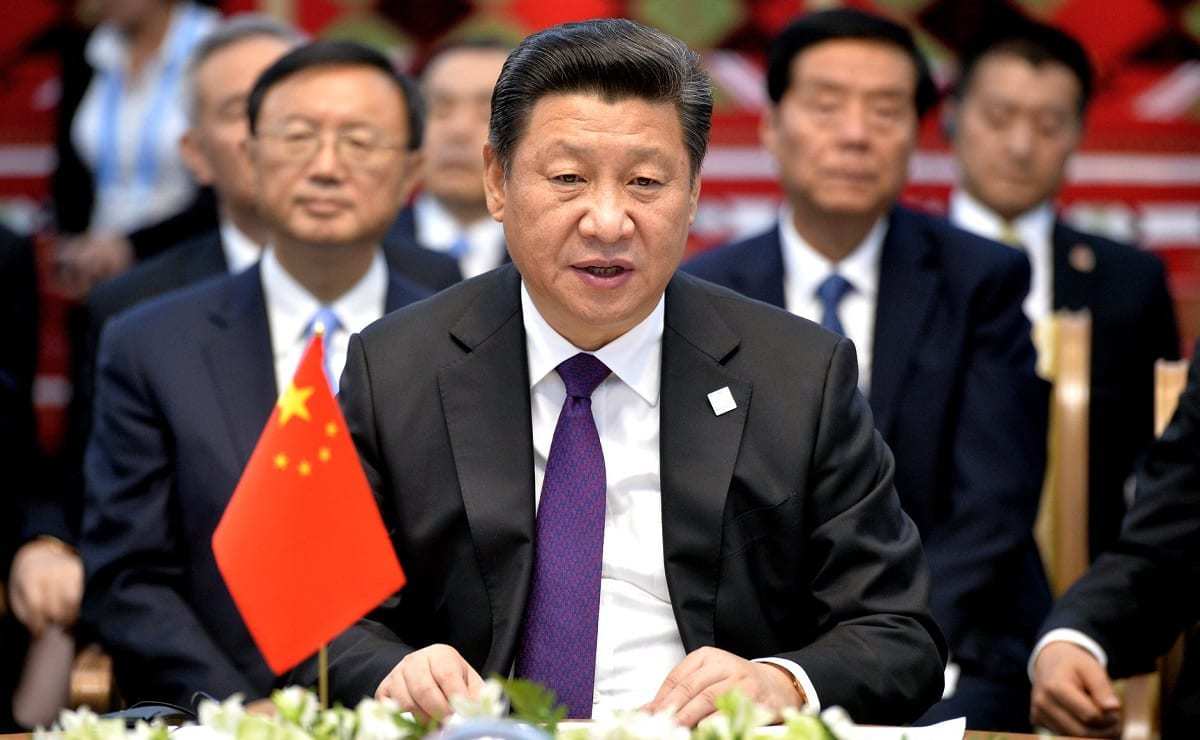

By allowing some forms of capitalism within their states, rising living standards worked to give the Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping regimes a patina of credibility and legitimacy, and allowed them to increase internal information control and oppression of any political dissent. Worse, U.S. business interests worked to crowd out and silence criticisms of these totalitarian regimes, despite their states’ now 20-year trajectory of greater and greater hostility toward the United States.

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia has severely and permanently undermined the un-written post-Cold War grand strategy of engagement – not only with Russia but with China too. Few believe, for instance, that China is currently evolving into a liberal democracy. Russia’s deep state – the siloviki (former members of the security and military services, who dominate the senior leadership of the major government agencies) – insulates the Putin regime from any notion of liberalization, just as communist party loyalists dominate all Chinese bureaucracies, the media, the police, and the national universities.

This historical tipping point should signal that the era of ignoring political ideology is over. The invasion of Ukraine has proven (once again) that totalitarian regimes do not evolve politically toward greater freedom; they do not move toward liberal democracy; they do not care to maintain or safeguard Western institutions. In fact, totalitarian regimes wish to subvert all of those advances. We know this because Putin and Xi tell us this and act on their words. They want the United States to decline, stumble, internally fracture, and fail. They wish to supplant the United States regionally (in the case of Russia) and globally (in the case of China).

In short, Putin and Xi want the United States to struggle internally and decline. U.S. policy for almost three decades now conversely has wanted Russia and China to flourish and evolve into liberal democracies. Their grand strategies have been working (with help from ourselves). Our strategy of engagement to affect political reform has evaporated. Yet nothing has replaced it to date.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, along with China’s takeover of Hong Kong and its implacable hostility toward the democracy of Taiwan, as well as increasing internal repression and control, has revealed that political ideology matters. In fact, ideology matters most. Political ideology is destiny.

There is no inevitable Thucydides Trap (the tendency towards war when an emerging power threatens to displace an existing great power); there is only the George Kennan Trap (totalitarian states trend toward greater internal control and confrontation with liberal democratic states). Totalitarian regimes are incompatible with modernity and cannot communally coexist with liberal democratic states.

States don’t engage in armed conflict simply because they become strong. Norway, Germany, and Japan – all with larger economies than Russia – may be economically competitive but do not physically threaten their neighbors, despite changes in their relative economic strength. None is building nuclear weapons, controlling information domestically, calling their neighbors Nazis, overflying weaker states, or assassinating their political opponents. States compete because of the political structure of their governments. Totalitarian states will clash with liberal democratic states inevitably.

It was cynical, self-serving, and delusional to argue that engaging and entangling the totalitarian states of Putin’s Russia and communist China would somehow lead them out of totalitarianism, though it was the strategy of most Democrat and Republican politicians since the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is almost as if U.S. business cynically assuaged U.S. politicians that the easy way – following the Siren song of Russian and Chinese markets – was the best way to achieve peaceful regime change from these autocracies.

No totalitarian state in history has chosen to commit suicide and evolve into a liberal democracy. Pro-Western authoritarian states – Taiwan, the Republic of Korea, Chile, Argentina – have evolved. But all totalitarian states have become more and more totalitarian until they collapse via some level of political turmoil or violence. Pro-Western authoritarian states argued that they were in necessary and temporary stages on the way to becoming secure liberal democracies. The United States shaped and encouraged their liberalization. The regimes of these stated were willing to reform, in response to the cajoling of the United States. In stark contrast, Putin, Xi, Khamenei, and Kim all see liberal democracy as threats to them personally and a diseases to their states. They don’t seek a path to liberal democracy.

Grand or national strategies do not necessarily need to be written down, though today such a document would certainly help. There likely already exists a majority opinion with Americans that the strategy of engagement has failed. What is lacking is a clear vision and policy from our national security leaders.

The Biden Administration, like its predecessors, to date has been reluctant to debate political ideology and instead wants to ‘deter’ everything it doesn’t want to happen. So far, this deterrence has failed in Ukraine, just as it failed in Georgia and Ukraine in the Bush and Obama Administrations. The current Administration has said almost nothing about the relevance of ideological differences between liberal democracies and totalitarian states – at least in the context of an overall, guiding, grand strategy.

Our grand strategy, however, cannot be mere deterrence. Deterrence is a military strategy for dissuading adverse occurrences. But deterrence must operate in the context of a larger positive vision of what the United States seeks to achieve in the world. Deterrence is unsuitable for a national strategy. Concepts of deterrence emerged prominently after nuclear weapons made traditional notions of victory following a nuclear exchange hard to perceive. The deterrence of nuclear engagement is appropriate. But deterrence alone does not address the realities of the political differences among the great powers. U.S. grand strategy in an era of totalitarian superpowers agitating for and violently pursuing political change cannot simply be the ‘deterrence’ of ‘pacing’ and ‘acute’ military threats.

The one and only grand or national strategy now must be to advance peaceful political change by advancing pluralism and liberal democratic institutions within these totalitarian states, much like the West did with the Soviet Union. Our NATO and Asian allies, the European Union, and all partners should adopt the same policy. States that attempt some middle road need to be challenged – there is no defending totalitarian rule or engagement any longer. It is inevitable that the current Russian and Chinese regimes will continue to challenge freedom; undermine international institutions; threaten neighbors; deceive their people; and commit violence. It is folly, for instance, to buy solar panels from China but allow the Chinese to emit twice as much CO2 as the United States with no plan to curb such emissions. Such policy is giving polluters and totalitarians our money. We cannot ignore this reality.

The phrase ‘regime change’ scares some, but it should not. The United States once directed such change toward the nuclear-armed Soviet Union and it collapsed from totalitarianism relatively peacefully. Enticing the totalitarian states of the 21st century to liberalize through ‘engagement’ was a policy of regime change via carrots (only). Denouncing totalitarianism, supporting dissidents, setting limits on economic engagement, de-coupling government investments, tying trade to CO2 emissions curbs, creating independent supply chains, and calling for political reform within these states is also a form of regime change: ‘strategic engagement with strings attached to effect political reform.’ Regime change is the strategy of these totalitarian states toward us; we should not be afraid to reflect the same. Our reluctance to adopt strong policy has furthered totalitarian truculence.

Our politicians and most academics are afraid to call for regime change since it evokes images of invasion and Iraq. Yet the President of the United States has called the leader of the state of Russia a war criminal who has pursued genocide. Mr. Putin cannot appear anywhere in the West again, or our values, institutions, and law will be rendered meaningless. North Korea will never flourish under totalitarian rule, nor will Kim Jong-Un ever choose to join the Republic of Korea. The endless wait for ‘moderates’ to change Iran is long past naïve. Chinese diplomats mock the United States daily. Russia and China work via information and cyberspace operations to undermine liberal institutions and U.S. leadership worldwide. We ignore the words and deeds of these totalitarians because our leaders are reluctant to accept the challenge or accept that our relationship with them is zero-sum.

The era of totalitarian regime change does not mean violence is inevitable, sought, or welcome. It simply means we must stop strengthening adversary states without condition (by trading with them; educating their students; allowing them to steal our intellectual property; giving them trade advantages …) in the naïve belief that their success will lead them to liberalize. It means we recognize that totalitarianism is incompatible with liberal democracy. The United States ought to adopt as policy that it will support, trade with, and embrace liberal democratic states and states that take steps to liberalize. Conversely, the United States should eschew and limit engagement with those that do not. We must de-couple our economy from that of Putin’s Russia and the Chinese Communist Party. But in addition, the United States ought to appeal directly to the people within these totalitarian states and inform them that they do have a choice. Such change, like with the Cold War, may not come easily or anytime soon.

As we did in the Cold War, the U.S. Government ought to support opposition parties to totalitarian rule. The United States should highlight dissidence and protect it where it can; teach political ideologies and their histories at home (our youth is oblivious to the relevance of ideology, given now a generation of ignoring its importance in academia); adopt a competitive economic strategy toward the totalitarian states (they have adopted such an attitude toward us); and demand political progress (i.e., reform) from Russia and China. Today, Russia and China agitate for political change around the world, while the United States is a status quo power. This dynamic must be flipped.

The current Russian and Chinese governments want Americans to be afraid to demand political progress from them. They achieve this through intimidation, influence operations, the corruption of U.S. academia and journalism, and scare mongering. That is why we must muster the political strength, will, and leadership to advance the only coherent national strategy left to us. We are in an era of zero-sum political competition, whether we like it or not. The strategy of engagement and enlargement is over; the strategy of regime change is upon us.

James Van de Velde, Ph.D., is a Professor at the National Defense University and an Adjunct Faculty Member at Johns Hopkins University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense or the U. S. Government.