In the run-up to the thirtieth anniversary of the lowering of the hammer-and-sickle banner over the Kremlin, a due- diligence Google search will not be necessary. “End,” “fall,” “collapse,” “demise,” and their many synonyms will undoubtedly dominate the descriptions.

All are misnomers that label the result without mentioning the cause: one of the greatest revolutions of modern times.

The Death of an Empire

To begin with, the August 1991 Revolution ushered in a new political and economic system and created a new state, post-Soviet Russia. Моre important still, like its predecessors, the English, and the French Revolutions among them, central to its drive was the precipitously deflated moral component of the ancient regime’s legitimacy — and the search for the one that responds to newly emerged definitions of human dignity.

This is not a fanciful explanation. It is the only one that fits empirically. A closer look at the alternative causes, which somehow continue to remain popular, quickly reveals their falling short. Until the political system began to unravel in late 1990, there was no economic crisis. Nor was there a major military defeat – indeed a defeat of any kind. On the contrary: by the mid-1980s the Soviet Union was at the apogee of its military prowess, at nuclear parity with the United States, in possession of the largest armed force in the world, with 5 million men under arms and in a total and unshakable control of its central-eastern European empire. While total defense expenditures were indeed very high, the Soviet people had seen much worse, had gotten used to monthly allotment of key staples, shortages, and lines. And in any case, terror and propaganda dealt swiftly and ruthlessly with any manifestations of public discontent.

Instead, Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost forced the country to look in the mirror no longer distorted by censorship and lies and recoil in horror. Suddenly, after seven decades of state atheism the quest for moral renewal filled with terms of faith that everyone thought the Soviet people had forgotten: cleansing, repentance, atonement. The key aspects of the Soviet state were put into sharp relief and became hotly contested individual moral choices rather than enforced certainties. What is known as “ultimate questions” were asked louder and louder: “Who are we? Do we live virtually and honorably? How should we live? What is virtue and what is evil? What is the proper, dignified relation between individual and state?”

The same passionate search for human dignity in liberty and democratic citizenship that led thousands to put their bodies between tanks and the Yeltsin’s “White House” during the three rainy days and nights in August 1991, two years before had college students stand in front of tanks in Tiananmen Square, and ten years hence would inspire Mohamed Bouazizi in his heroic death and touch off the Arab Spring.

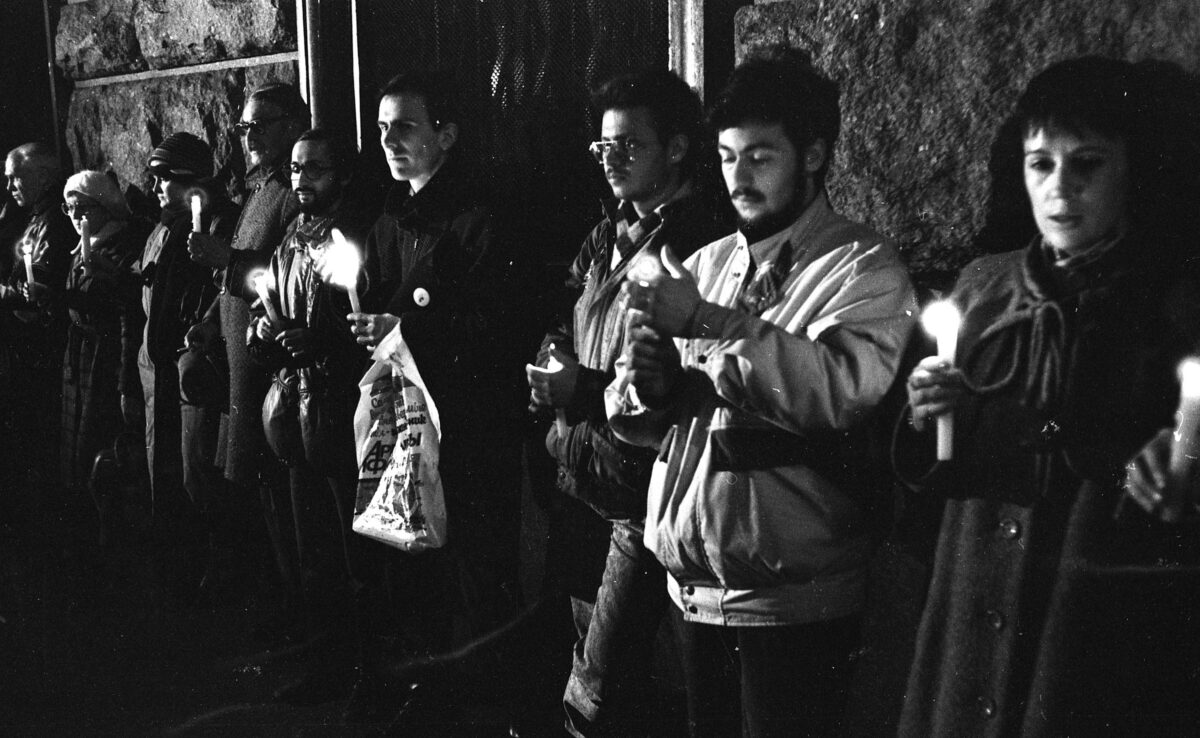

The first public rally near the KGB building in Moscow on Lubyanka Square in a memory of Stalin’s victims on the Day of Political Prisoners, 30 October 1989

Inevitably, the revolution resulted in a radical change in Russia’s behavior in the world. The most explicit declaration of this connection was made by Boris Yeltsin when he addressed the nation on December 29, 1991, four days before he abolished price controls in the foundation of the Soviet economic system. Together with the state-owned economy, Yeltsin said, Russia was ridding itself of “the militarization of our life”. The Iron Curtain that had separated Russia from “the whole world” was no more.

Putin: The Defender of Russia Against the West

As the West is at pains to glean the purposes of the militarized drama Putin is enacting on the Ukrainian border, instead of legitimizing his fantasy of NATO’s “creeping threat” by suggesting that NATO may “accommodate” some of Russia’s alleged grievances, the White House and its allies may instead look at the choice Putin made in the run-up to his third presidency 2012. It was then when Putin reinvented himself as a wartime president by replacing economic progress and growth of incomes as the foundation of his regime’s legitimacy with that of the defender of the Motherland from the perennially aggressive West.

No revolution ever lives up to the promise of its initial slogans, and most are followed by restorations. (Unusual in many other ways, the American Revolution is exceptional in this regard as well). Although never complete, leaving in place some of the major changes wrought by the revolutions, these reversals tend to be lengthy. It took almost four decades from the execution of Charles I and the constitutional monarchy of the Glorious Revolution. The French had gone through two Empires and four mostly short-lived Republics before DeGaulle’s Fifth, in essence, another constitutional monarchy in the guise of a presidential republic.

After twenty-two years in the Kremlin, in another two years Putin will embark on a presidency-for-life in 2024, when, at seventy-two, he will be looking at two more six-year terms. Yet both the history of great revolutions of modernity and Russian history strongly suggest that his restoration will not survive him.

In the meantime, let’s celebrate Russia’s own Glorious Revolution of 1991.

Leon Aron, who was born in Moscow and came to the United States as a refugee in 1978, is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). He studies Russian domestic and foreign policy, US-Russia relations, and the economic, social, and cultural aspects of Russia’s post-Soviet evolution. He is currently working on a book on the ideals, beliefs, perceptions, and domestic political imperatives that shape Putin’s foreign policy. Aron is the author of Yeltsin: A Revolutionary Life and Roads to the Temple, among other books.