DDG(X): Do we have a cost issue? Caveat emptor. Let the buyer beware. Denizens of the military-industrial complex have an exasperating habit: how many times have you heard a spokesman for an armed service or defense firm talk about some future platform, sensor, or weapon as though it already exists and is a known, proven, reliable quantity—and thus constitutes a sure bet for the taxpayers?

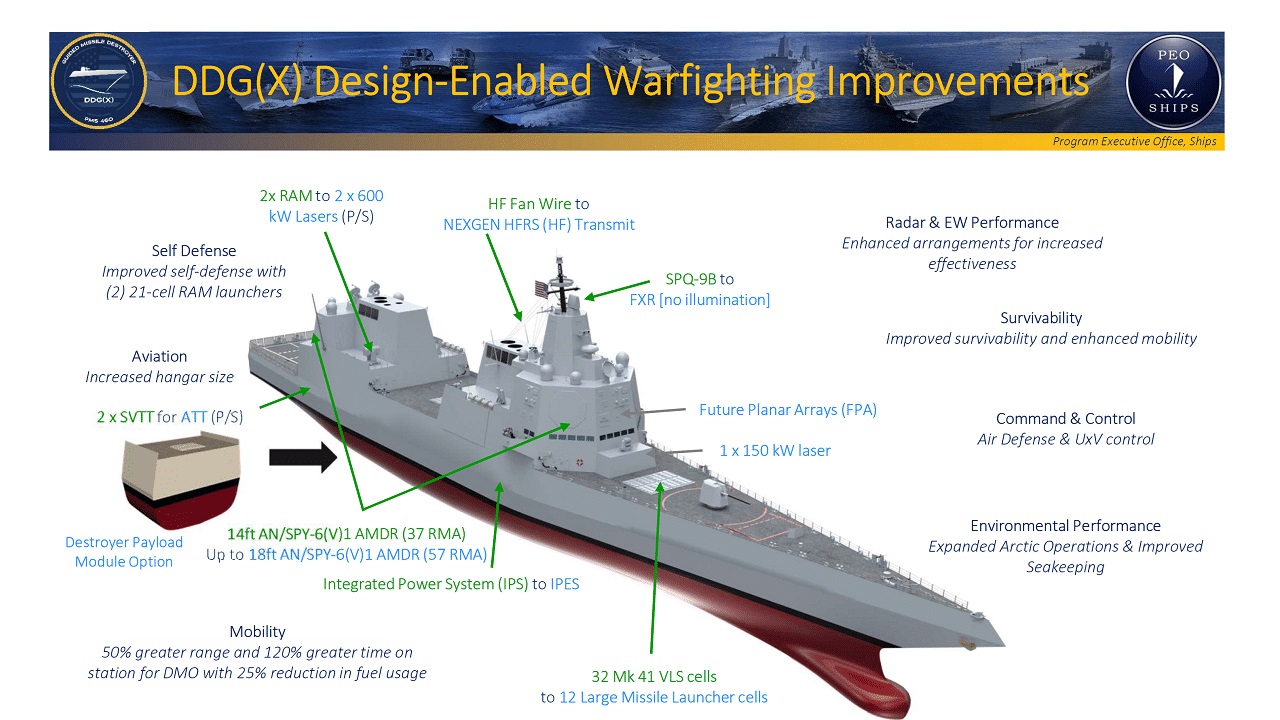

DDG(X). Image Credit: U.S. Navy.

It’s a regular occurrence if you follow the daily news out of the defense world. But the habit of downplaying risk masks a plain truth, namely that even the most elegant idea or design is a hypothesis. It remains a hypothesis until reduced to engineering, subjected to rigorous field trials, and vindicated—or not—in the real world. It may suffice once amended to meet the test of reality. Or it may not. Failure is always an option.

Lawmakers must insist that the scientific method prevail, in the world of arms as throughout public affairs. Not every great idea is actionable.

Nevertheless, the habit of downplaying prospects for failure while playing up visions of success seems graven on the cultures of both the military and defense-industrial sectors. Here’s an example lifted at random from an early-bird newsletter flung over my metaphorical transom each morning. Inside Defense reported that the first copy of the U.S. Navy’s next-generation guided-missile destroyer, dubbed “DDG(X),” will cost around twice what each DDG-51 Flight III Arleigh Burke-class destroyer—today’s state of the art—runs taxpayers.

The Inside Defense story cited a report from the Congressional Research Service, a nonpartisan analytical arm of the national legislature. (CRS products are models of sobriety when evaluating military programs. No hype there.) Notes the report’s author, the redoubtable Ron O’Rourke, the leading-edge DDG(X) will cost some $3.5 to $4 billion according to navy estimates. By contrast each DDG-51 Flight III, the latest variant of a model in service for the past thirty years, sets the taxpayers back about $2.2 billion.

Whoa. Doubling the price of something while on a more or less fixed budget spells trouble.

Rather than let brute numbers shout an alarming message, however, Inside Defense solicited comment from the U.S. Navy. Navy spokesman Lieutenant Megan Morrison provided context, rightly pointing out that the first ship in any class is inherently more expensive than subsequent copies. In large part that’s because time and money spent working out the kinks in a new design are included in the lead vessel’s price tag.

In other words, getting things right up front costs you. But one-time costs fall once the more or less perfected design goes into mass production. How far the per-unit price falls depends on how ambitious the design is, how many copies the navy wants—the more the cheaper, since the program’s total cost is divided among them—and kindred variables.

So far, so good.

But Morrison went on to assert that “considering the significant increases in efficiency, mobility, capability, capacity and flexibility that DDG(X) brings to the fleet, the increase in cost for DDG(X) is reasonable.”

Read that again. She’s saying that a ship of war that remains unbuilt—and that apparently doesn’t even have settled specifications as of yet—brings all these wondrous things to the fleet, and that therefore the outlay for the new class is reasonable.

That’s a mighty confident claim for a vessel whose keel won’t be laid until 2028 assuming all goes as planned between now and then. A humbler claim, truer to reality, would go something like this: if the design delivers the new capability it promises, the increase in cost for DDG(X) will be reasonable. And a corollary would be: it may not deliver the promised capability, in which case the increase in cost would not be reasonable.

See how seductive the present tense is? It obscures the possibility of subpar performance or outright failure. Using it amounts to claiming that an if/then proposition has been proved. To wit, if Congress invests X dollars in this program, then the armed forces will receive Y amount of efficiency, mobility, capability, capacity, and flexibility, to repeat Morrison’s list of DDG(X) characteristics. But that proposition hasn’t been tested, let alone proved.

Let the buyer beware.

This is not to pick on Lieutenant Morrison; far from it. She’s a junior officer acculturated to the dominant way of thinking and speaking among military folk. The prevailing “can-do” culture pervading the armed forces biases members of that community against admitting that failure is a possibility in anything they do. Success is our public trust. We tend to accentuate the positive while softpedaling—or keeping mum about—the negative.

A similar can-do ethos animates defense firms, with the profit motive imparting an additional accelerant. Pick a “sponsored” post from any defense outlet, read it, and relate it to your daily life. We’re all constant targets for ads nowadays. Heck, my Kindle tries to sell me a new title every time I flip it open to resume whatever e-book I’m reading. How many companies are given to confessing doubt about their wares when hitting you up on TV, the internet, or social media?

Few.

The chief difference is that defense suppliers are advertising manufactures that don’t yet exist and that doubters can’t put to the test before deciding whether to fund them. Company leaders can stress the excellent idea while bypassing doubts that it can be brought to fruition. Yet skepticism is the soul of any scientific-technical enterprise, including martial affairs in this über-high-tech age. Waving it aside subverts the process of developing and fielding implements the United States and its allies need to stymie tyranny while accomplishing positive goals in the world.

So overseers of the military-industrial complex must challenge overconfident claims about DDG(X) or any other program. Do I hope the new destroyer fulfills its promise? You bet I do. But hope is not a way to run a defense program. Not a good way, at any rate.

Skepticism is a virtue much in disrepute of late, when contesting some established narrative triggers claims that a skeptic is pushing misinformation or disinformation. But it’s a virtue worth rediscovering nonetheless. It should set your doubt-o-meter a-jangling when someone from the arcane demesne of military technology, programs, or budgeting uses the present tense to tout some thingamabob that has yet to be constructed or put to field trials.

That’s doubly true of a program like DDG(X) that remains in the design phase yet carries a hefty price tag. Reality is an unsparing arbiter of whether engineers can transmogrify an ingenious idea into a working combat system. It must rule.

Recent history warrants caution—witness recent U.S. Navy procurements such as the littoral combat ship, DDG-1000, Ford-class aircraft carrier, or F-35 joint strike fighter. All of these once-celebrated programs came in late, went over budget, or fell short of design specs. Or sometimes all three: indeed, navy chieftains apparently regard the LCS as a failed venture, since they’ve been clamoring to rid the fleet of youthful hulls.

Bottom line, past hype is no guarantee of future results. As a rule defense folk are upstanding people with no intent to mislead. But incentives and disincentives intrinsic to the profession of arms encourage a bubbly, relentlessly upbeat, and thus deceptive culture when it comes to weapons procurement. That culture muffles doubt.

So Congress and the American people must pose hard questions when buffeted by hard sell. They should ask:

Says who?

Dr. James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College and a Nonresident Fellow at the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Future Warfare, Marine Corps University. The views voiced here are his alone. Dr. Holmes is a 19FortyFive Contributing Editor.