Yes, the Zumwalt-class can be rebooted: Months after the terror attacks of September 2001, the Navy announced a new three-vessel “Family of Ships” reflecting a post-Cold War sense of blue-water dominance. Those ships—the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), the 21st-century destroyer (DD21, now the DDG 1000), and the 21st-century cruiser (CG(X))—emphasized operations in the littorals and in support of land campaigns, in addition to high-end Integrated Air and Missile Defense (IAMD). Two decades later, the fleet architecture envisioned in these ships does not exist, falling victim to strategic shocks that drove near immediate obsolescence—the extended “War on Terror” and the rise of China as a peer competitor—in addition to questionable programmatic decisions resulting in significant cost overruns.

PACIFIC OCEAN (Dec. 8, 2016) The guided-missile destroyer USS Zumwalt (DDG 1000), left, the Navy’s most technologically advanced surface ship, is underway in formation with the littoral combat ship USS Independence (LCS 2) on the final leg of its three-month journey to its new homeport in San Diego. Upon arrival, Zumwalt will begin installation of its combat systems, testing and evaluation, and operation integration with the fleet. (U.S. Navy photo by Petty Officer 1st Class Ace Rheaume/Released)161208-N-SI773-0401

The Navy canceled CG(X) outright, and while it produced the LCS class in numbers, the Navy is keen to decommission many of them as being unsuited to high-end conflict. This leaves the three ships of the Zumwlat-Class, 14,000-ton multi-mission warships featuring an integrated power system that both propels the ship and creates several times the amount of electricity found on even the Navy’s newest destroyer class, the Flight III DDG. The Zumwalts have had a rough go of it in joining the fleet, due to both program mismanagement and industrial base problems driven by the Navy’s decision to restart the DDG 51 line. Lately, though, there is momentum building to spend the money necessary to achieve the significant war-fighting advantages these ships could provide, as Hope Hedge Seck recently detailed here in a 19FortyFive article. The Department of Defense (DoD) and the Navy should proceed aggressively to achieve these benefits.

The first of these benefits is the installation of Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) missiles, work that is due to begin on USS Zumwalt (DDG 1000) in late 2023 and is expected to take two years, with the remaining two hulls undergoing the CPS installation as schedules permit. Zumwalt is currently deployed in the Indo-Pacific, and it is likely that she will be equipped with an unspecified number of hypersonic CPS missiles on her next deployment.

Five to seven years after beginning work on Zumwalt, the Navy could modify all three hulls to employ this significant capability. Resources necessary to achieve these modifications will necessarily compete within the Navy’s budget with other priorities that include recapitalizing the ballistic missile submarine line, the airwing of the future, the next generation of helicopters and or unmanned vehicles employed by the surface fleet, and the next-generation destroyer. Given the rising importance of deterring Chinese aggression and the centrality of naval forces to this task, DoD should seek sufficient funding from the White House to ensure that the Navy does not make ruinous choices among current readiness and future capability investments.

Beyond CPS: The Maritime Dominance Destroyer

The fielding of CPS in the Zumwalts is only the beginning. As the Navy begins to evolve the AEGIS Combat System into the Integrated Combat System, the existence of a troubled, three-ship “unicorn” combat system in the ZUMWALT class cannot be long abided. Work must begin in earnest to reach a technical solution to integrating AEGIS into these ships without incurring undue risk to the aggressive CPS fielding plan. Additionally, the maintenance periods necessary to install CPS should target known Hull, Mechanical, and Electrical (H, M&E) issues that have accumulated since the ships left their building yard. Most important of all though is that the Navy and its Pacific Fleet Commander must devise and implement a coherent concept of operations for this ship, one reflective of dedication to regional maritime dominance.

First, the Navy should determine whether the three-ship class can support one ship always deployed to the Indo-Pacific. This “1.0” presence goal would drive other decisions such as where to base the ships and what infrastructure enhancements are needed to accommodate them if any. The time is now for these decisions and concomitant investments.

Having a CPS-equipped DDG 1000 continuously deployed sends a strong message of conventional deterrence to both China and North Korea, as would the weapons employed (Tomahawk, Standard Missiles) from the eighty-cell Peripheral Vertical Launch System (PVLS) each ship fields. The ship would not be employed as part of a traditional Carrier Strike Group (CSG). Rather, it would be employed as the lead of surface and amphibious task groups comprised of unmanned ships, destroyers, LCS, and amphibious ships, and would normally embark a staff to perform these larger command and control (C2) functions.

Second, as part of the transition to AEGIS and then to the Integrated Combat System, the Navy should fit the ships with a proper air and missile defense radar. Options include variants of the SPY-6 AMDR or the SPY 7. This would increase the ship’s capability and lessen the burden of providing IAMD to this capital asset that would invariably fall to another ship.

Third, while all three ships are currently being outfitted to accommodate manned helicopters (and should be capable of receiving and employing them), they should primarily operate unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). For the time being, each should employ several MQ-8C Fire Scouts to extend the range of the ship’s radars and other surveillance systems, and the Zumwalts should be first in line to receive longer-range Medium Altitude/Long Endurance (MALE) UAVs out of the Navy’s Future Vertical Lift Maritime Strike program. Moving beyond UAVs, as the Navy fields its desired fleet of Medium Unmanned Surface Vessels (MUSV) and Large Unmanned Surface Vessels (LUSV), the DDG 1000’s should serve as C2 “shepherds” to the unmanned “flock”, to include Sailors trained to perform corrective maintenance on unmanned platforms, as necessary. Fears of unprotected LUSVs equipped with dozens of missiles each falling into the hands of adversaries should be mitigated by the constant presence nearby of a powerful DDG 1000.

In peacetime, DDG 1000 and its embarked staff provide conventional deterrence by acting as a forward-deployed C2 node, and through the provision of forward-based combat power and hardened staying power. By integrating and coordinating the capabilities of other presence forces, the DDG 1000 anchors a more powerful presence force that deters adversaries through 1) the perception that aggression will be unsuccessful or dramatically delayed (denial); and or 2) the perception that the response will far outweigh the putative benefits of aggression (punishment). DDG 1000 accomplishes this deterrence through its ability to strike land and sea targets at range and with alacrity, by exercising command and control of widely dispersed forces, and by presenting a hardened but fleeting target to the adversary. In war, DDG 1000 leverages both theater and local ISR environments to seek out and destroy the enemy fleet while menacing his land-based formations at range. In certain situations, the ship’s stealthy profile when operating in a passive targeting network can provide for a fast response to events ashore such as the positioning of a land-based mobile cruise or ballistic missiles.

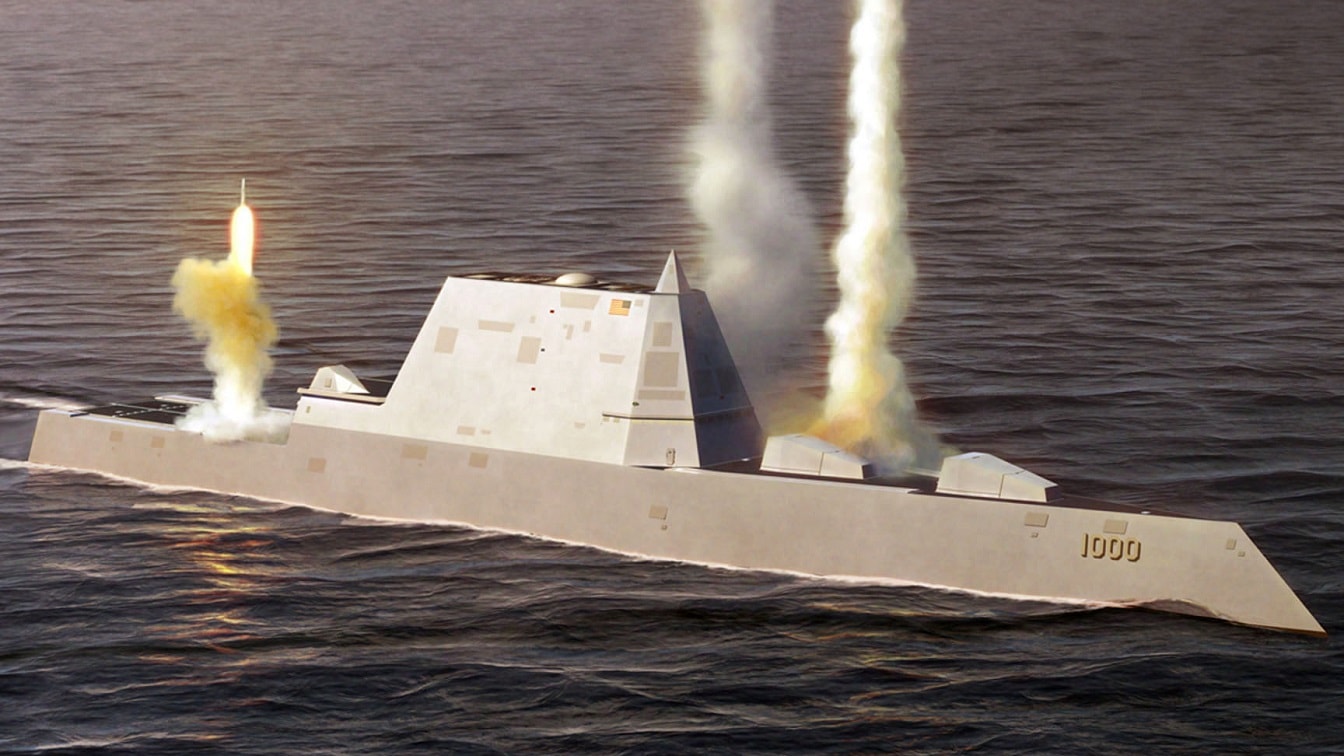

Zumwalt-class destroyer. Image Credit: Raytheon.

Conclusion: The Zumwalt-Class Can Be Rebooted

Visually menacing, electronically diminutive, and physically impressive, the upgraded DDG 1000 and an embarked command element will provide the Pacific Fleet Commander with an unmatched capability for the C2 of regional sea control and strike operations, and the deterrence punch of CPS and dozens of long-range strike weapons. This future will only be realized if the Navy plans for it and DoD resources it without hobbling other Navy priorities. The chance exists to create in the Zumwalt-class, a ship that while resembling the intentions of its designers, evolves into a truly dominant 21st-century destroyer. Now is not the time to wobble.

Bryan McGrath is the Managing Director of The FerryBridge Group, a national security consultancy. All opinions expressed are his own. You can follow him on Twitter: @ConsWahoo.